Let me start out by stating the obvious. Everyone who rides a bicycle in Chicago, or doesn't because they don't feel safe doing so, knows that our city is a less-than-ideal place for cycling.

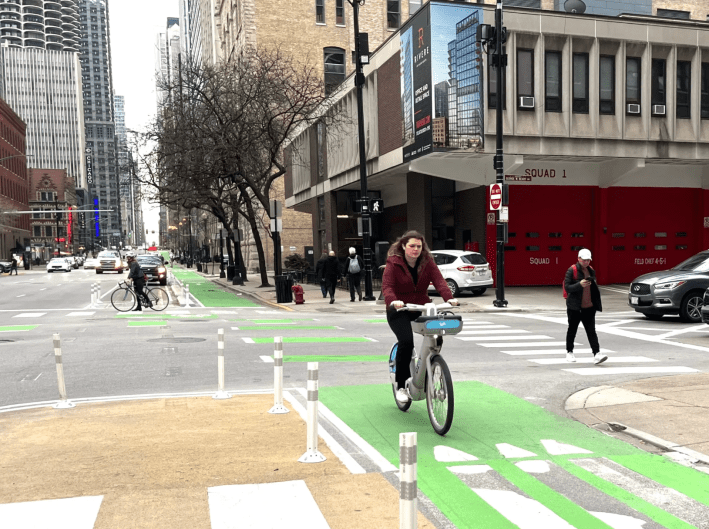

Yes, we've got some very nice off-street paths (Lakefront Trail, Bloomingale/606 etc.); a vast, flat grid with lots of mellow side streets to ride on; and an ever-expanding quantity of protected bike lanes and Neighborhood Greenways. And we've got the extensive Divvy bicycle-share system; and vibrant bike commuting, recreation, and advocacy scenes.

But Chicagoans who ride, or are afraid to, know that our city has lots of reckless, intoxicated, and/or distracted drivers, and every year they seriously injure and kill many people on bikes. We've got too many super-sized roads where speeding is the default, and deadly crashes are common. And while our bikeway mileage is growing every year, we still don't have a citywide, connected network of low-stress routes. That's largely due to our Byzantine ward system, which allows alderpersons to veto sustainable transportation projects in their districts.

People for Bikes consistently ranks Chicago as a godawful place to ride

So Chicago definitely has room for improvement when it comes to bike-friendliness. That said, despite what the Boulder-based, bike industry-funded nonprofit People for Bikes' declares every year in its annual City Ratings report, Chicago is not one of the very worst large U.S. cities for biking!

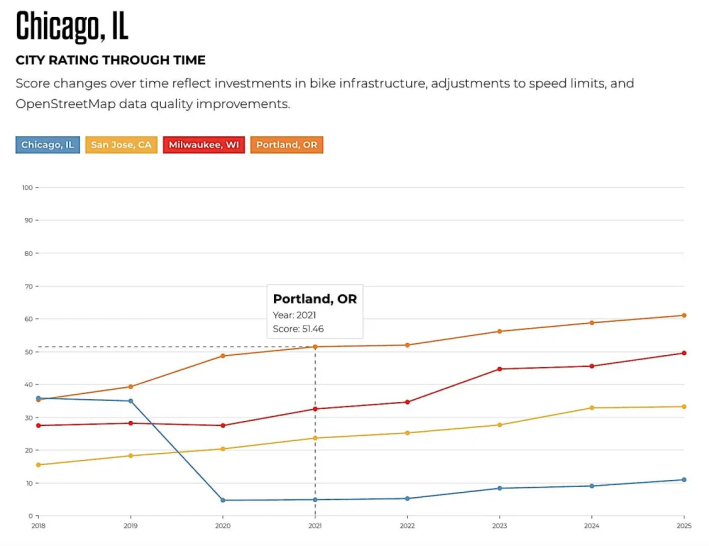

I try not to beat a flat bicycle tire too much every time People for Bikes puts out its new rankings with Chicago near the bottom. And last June, I stayed reasonably polite when I discussed the absurdity of the 2025 report ranking our city (with 11 out 100 possible points) well below car-centric places like Jacksonville (18), Los Angeles (25), and Atlanta (31). These cities have lower cycling mode share than Chicago, and higher fatality rates.

And this year we were tied with Houston for seventh-from-last place, out 74 U.S. cities over 300,000 people. While that auto-bound Texas town has 400,000 fewer residents than Chicago, it consistently sees more bike deaths. While our city averages about five cycling fatalities a year, tragically Houston saw eight bike deaths in 2024, and a staggering 16 fatalities in 2023.

In that June SBC post, I noted that People for Bikes' rating system is harsh to the Windy City largely because it gives inordinate weight to the fact our default speed limit is 30 mph. That's higher than many truly car-choked burgs. More on that in a bit.

Streetsblog Chicago recently requested an interview with PFB on ratings

On June 30, I emailed our post to a person doing press for People for Bikes, and proposed that I interview someone from PFB about their new rankings. (I interviewed one of their staffers last year before the 2024 study was released.)

Admittedly, I took off the kid gloves in that email. "If someone from PFB is interested in once again discussing why [they] don’t consider it to be malpractice to, year after year, rank Chicago far below peer cities with much lower bike mode share and much higher fatality rates, simply based on a 5 mph speed limit difference, I’d be happy to schedule a phone interview this week," I wrote. "Hopefully, people aren’t taking [their] Chicago rating seriously, partly because Streetsblog Chicago unpacks it every year. But if they did, it would surely discourage locals and visitors from riding bikes here, which seems awfully counterproductive to the purpose of [their] ratings."

On July 8, the press person politely wrote that they'd passed on my message to the relevant People for Bikes folks and would let me know if they had comments or questions.

"Thanks," I responded. "In a nutshell, the attached image is the smoking gun: [It says, in effect,] 'We used to consider Chicago to one of the very best large U.S. cities for biking, up there with Portland. But in 2020 we changed out rating system [to put more emphasis on speed limits], and now we consider Chicago to be one of the very worst large US cities for biking.'"

"I mean, if [PFB] can’t accurately rate Chicago using [its] system (and I haven’t noticed any other cities with such lopsided rankings), [they] should just stop including us in [their] report [emphasis added], because [they're] currently doing more harm than good for biking in our city," I concluded.

I never got a response.

After Streetsblog Chicago requested an interview, PFB instead ran a new post "using Chicago as a case study"

About a week after I sent my last email to People for Bikes on July 16, They posted a follow-up article. It's titled, "Six Things Any City Can Do to Improve Bicycling: Using Chicago as a case study, we unpack how PeopleForBikes' SPRINT principles can help cities big and small become great places to ride."

Sounds like constructive criticism, right? Nope, instead PFB doubles down on their flawed rating system that absolutely does not work for Chicago. Let's look at what they got wrong again, as well as a few accurate Second City critiques they made.

PFB blamed disconnected bikeways and scary intersections for Chicago's abysmal rating, but the real reason is a 5 mph speed limit difference

"Chicago completed more than 30 bike projects in the past three years but its network remains largely fragmented, with only a modest six-point improvement in its overall score in that same time," says the anonymous PFB article. "Many projects remain disconnected from other parts of the bike network, while dangerous intersections pose a significant safety challenge."

Sure, that's a largely accurate statement, similar to what I said at the beginning of this post. But it's not as if Omaha, which got more than three times as many points as Chicago this year at 36, is a paragon of connected, low-stress bikeway installation. When I researched that subject in 2022, the reported birthplace of the Reuben sandwich had exactly one protected bike lane, but back then it had more than five times as many People for Bikes points as us.

So what's the real reason People for Bikes thinks that the hometown of singer-songwriter Matthew Sweet is an exponentially better place to ride than Chicago? The deciding factor is the difference between a "25" and a "30" printed on residential speed limit street signs.

"Speed is a leading factor in traffic fatalities across the country, and reducing vehicle speeds is one of the simplest yet most effective first steps to improving road safety for all users," People for Bikes noted in the recent article. "Recently, a proposal to reduce citywide speed limits in Chicago stalled in a close City Council vote of 28-21."

Yep, that's all true, and Streetsblog Chicago heavily advocated for lowering our city's speed limit. We noted that peer cities like New York saw dramatic reductions in dangerous speeding and pedestrian fatalities after adopting 25 mph limits.

To their credit, People for Bikes says they're helping Chicago advocates brainstorm ideas to revive our speed limit ordinance. Read Streetsblog's discussion of that subject with sustainable transportation-friendly Ald. Andre Vasquez (40th).

So I agree with People for Bikes that a 5 mph speed limit reduction would make a big difference for helping Chicago become a safer place to ride. I just don't think the posted limit is the be-all and end-all for determining whether a street is a safe and pleasant place to ride, or a city is bike-friendly.

"Chicago has put in the work in recent years to build more protected bike lanes," People for Bikes acknowledged. Correct, in 2024, the Chicago Department of Transportation installed more than 15 miles of PBLs and almost 16 miles of Neighborhood Greenways. "Unfortunately, intersections remain high-stress and many of these new projects are not connected." Right, but again, that's even more the case in many cities with far higher rankings than Chicago, because People for Bikes makes a 5 mph speed limit difference such a huge factor in its rankings.

PFB said Chicago should "learn" from West Coast cities about upgrading PBLs with concrete, and road diets, but we've done those things for years

Under "Lessons From High-Scoring Cities," People for Bikes writes, "Seattle, which received a 2025 City Ratings score of 66, introduced plans to make many of its protected bike lanes more durable by replacing flexible posts with hardened barrier materials."

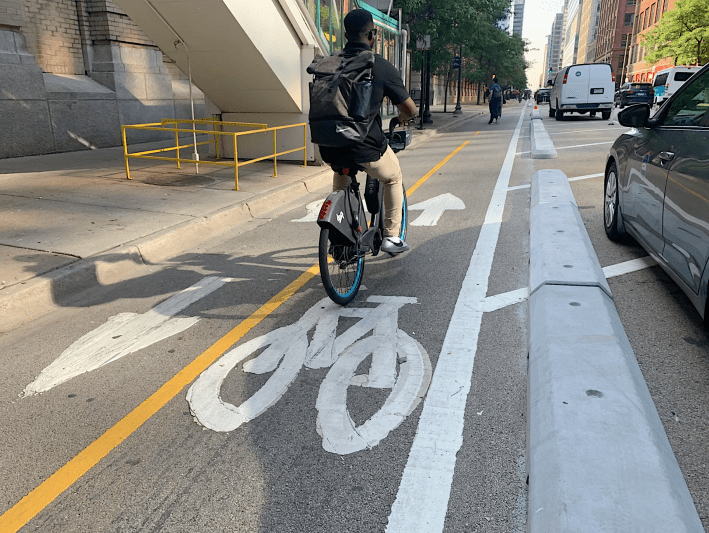

That's not much of a "lesson" for Chicago, since CDOT has been doing the exact same thing for more than two years.

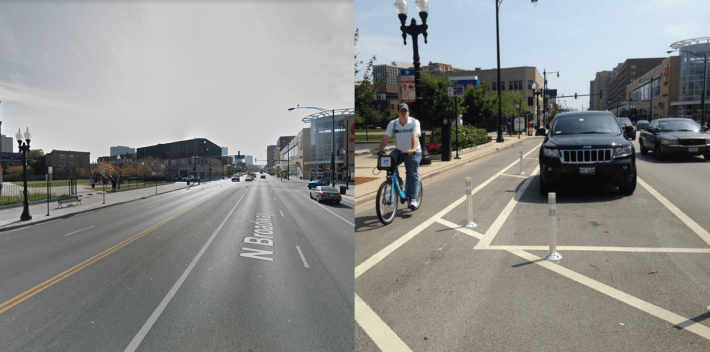

Another supposed learning opportunity for Chicago is road diets. "San Francisco (2025 City Ratings Score: 63) improved safety along California Street by reducing a four-lane roadway down to three," People for Bikes writes.

You mean like Chicago did on streets like Broadway, Lawrence Avenue, and South Chicago Avenue more than a decade ago? Geez, is there some kind of "Midwesterners are slow on the intake" bias going on here or what?

Perhaps the most valid statement in the recent People for Bikes article is, "Many of Chicago’s new protected bike lanes don’t connect to other parts of the city’s bike network, creating fragmented segments that don’t safely allow people to travel to everyday destinations by bike."

Indeed, as I've written before, it isn't very helpful when CDOT installs short snippets of protected bike lanes that don't connect with any other low-stress bikeways. Again, that's largely due to our Medieval "aldermanic prerogative" system, the de facto ability of Council members to nix protected lanes that cross into their (bizarrely gerrymandered) fiefdoms. But I do think CDOT is getting better at planning longer low-stress routes that actually go somewhere.

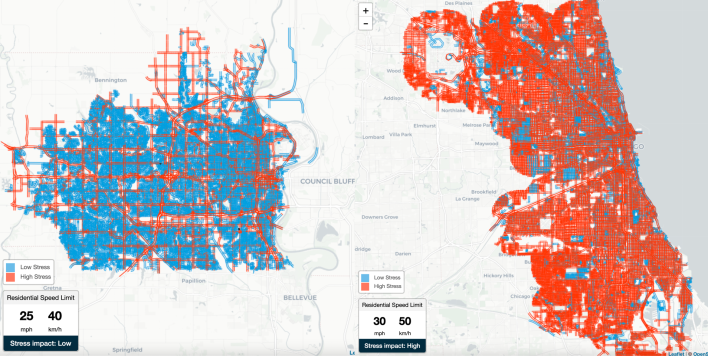

PFB revealed its ignorance of Chicago cycling with its binary "low stress" / "high stress" Bike Network Analysis tool, and laughable mapping results

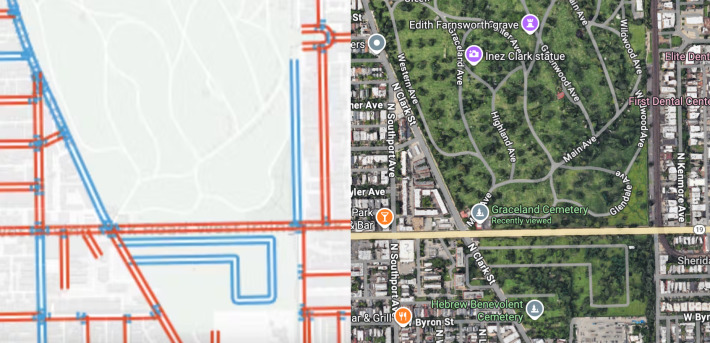

People for Bikes' statement would be more convincing if the map detail they used to illustrate it, shown below, indicated that they have any idea what the heck they're talking about when it comes to Chicago geography. (As it happens, this map section includes SBC HQ, so I know this area very well.)

"A protected bike lane on Clark Street begins and ends on a high-stress road, making it difficult to connect to other parts of Chicago’s bike network," People for Bikes states.

Yes, it's annoying that the PBLs on Clark, the diagonal street with the blue "low stress" designation, only runs for half a mile, although CDOT has proposed extending it north several more blocks. (Update: After this article was published, SBC learned that construction is starting on this project on Monday, August 18.)

And, sure, while Clark north and south of the PBLs is a two-lane street with "shared-lane markings," that doesn't work for people who aren't comfortable sharing the road with drivers on a main street.

But it's silly to label just about all the side streets on this map in red as "high stress" simply because they have 30 mph speed limits. These include popular cycling routes like Ravenswood and Greenview avenues, relatively low-traffic, leafy residential north-south streets I included on my Mellow Chicago Bike Map. The youth bike camp Pedalheads seems to agree with me that Greenview is not "high stress," because I recently saw them leading a class of youngsters on the avenue.

And you see that loop-shaped route on People for Bikes' map inset, colored blue as a "low stress" bike route? That's actually a road within a cemetery, LOL.

So I realize that People for Bikes' intentions are good. But they really need to come up with a rating system that's fairer to our city, and demonstrate that they actually have some understanding of local geography. Otherwise, it would be best for them to keep Chicago's name out of their mouths.

Check out People for Bikes' 2025 City Ratings report here.

Read Streetsblog Chicago's initial response here.

Read PFB's article, "Six Things Any City Can Do to Improve Bicycling" here.

Do you appreciate Streetsblog Chicago's paywall-free reporting and advocacy on sustainable transportation and traffic safety issues? While we officially ended our 2024-25 fund drive last month, we still need another $44K to keep the (bike) lights on in 2026. We'd appreciate any leads on potential major donors or grants. And if you haven't already, please consider making a tax-deductible donation here to help us continue publishing next year. Thank you!