Here at Streetsblog Chicago, we try not to pull punches when it comes to calling out issues that prevent our city from becoming a truly bike-friendly metropolis. Those can range from City Council members blocking the construction of safe bikeways in their districts, to protected lanes that turn into canals after rainstorms.

On the other hand, for the last few years, this website has responded to City Rankings by the national advocacy group People for Bikes, which rated Chicago as one of the absolutely worst large U.S. cities for cycling.

This time we tried a somewhat different approach this year by reaching out to PFB before this year's rankings come out on June 25. The organization's Senior Director of Local Innovation Martina Haggerty graciously agreed to chat with me about why Chicago has consistently gotten low numbers in the City Ratings, and whether anything will be different this year. The interview has been edited slightly for brevity and clarity.

John Greenfield: To start this interview off on a good foot, let me just say that the People for Bikes studies have had a positive effect on Chicago by drawing more attention to the need for the City to create a connected, protected, citywide network of bikeways. They've also pointed out that our default 30 mph speed limit is too high, and that we could improve safety for bike riders, and pedestrians and motorists, by lowering our speed limits.

So that's had a couple of positive effects on Chicago. Last year the Chicago Department of Transportation did build a lot of protected bike lanes, reportedly the most that they've built in any year. And also right now there's a campaign to lower the city's default speed limit from 30 to 25. So that couldn't have hurt things, that the People for Bikes reports highlighted the need to do those things.

But if you don't mind, I'd like to quickly go over a couple of things that I think have been problematic about the way the reports have been done in the past. And then I'd like to ask you about what the plans are for this year.

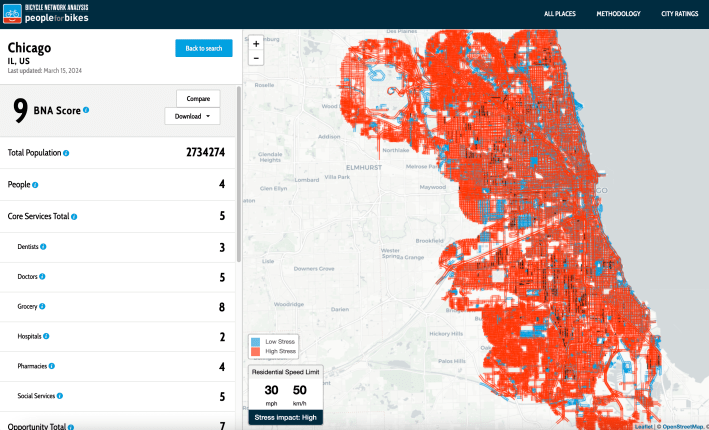

In the past few People for Bikes reports [2020, 2021, 2022, 2023], Chicago has been rated as one of the very worst large U.S. cities for biking. In the 2023 report our city got seven out of 100 possible points. It was listed in 67th place out of 69 large American cities, behind cities like Phoenix, Jacksonville, and Houston, that have a lot fewer bike lanes, probably a higher bike fatality rate, with likely a lot less biking going on. Chicago was listed as 161st out of 163 big cities around the world.

And so we talked to Rebecca Davies [PFB's City Ratings Program Director] in 2022, she told us that the main factors in Chicago's low ratings were that 30 mph speed limit, and the lack of a connected network of protected bike lanes.

An issue I had with that rating system is that on your Bicycle Network Analysis for last year, basically every street in Chicago is shown in red as being a high-stress street. And that includes our entire network of residential streets, which do have 30 mph speed limits, but they are generally low-stress places to ride your bike. It's not like it's that common for people to speed down them.

Rebecca Davis said that if Chicago was to lower our speed limit to 25 – which we're trying to do – that would raise our ranking with People for Bikes to be one of the best large U.S. cities for biking.

Now, a recent report found that cycling in Chicago grew by a 119 percent over the last four years, and that was the most of any of the ten largest American cities. That included a 166 percent increase in the number of people of color riding bikes. So obviously there's a big contrast between that and the previous People for Bikes reports.

Thanks for hearing me out on that stuff. Let's talk about, is anything going to be different about the People for Bikes study this year that will, in my opinion, more accurately reflect the state of biking in Chicago? Things are not perfect here, but I don't think they're godawful either.

Martina Haggerty: Thanks for reaching out, and we appreciate the ongoing interest in the program and are happy that it's continuing to facilitate a conversation about how critical issues like lower speed limits, and protected bike lanes, and complete bike networks are. So thanks for continuing to elevate it in that way.

As you know from your past conversations with Rebecca, the program uses very objective data to assess the quality of low-stress bikeways. So we take into account things like safe speeds, protected bike lanes, the quality of connectivity through intersections, how that forms complete networks. So we take all of that data, and that feeds into it. And this is all based on best practices and research, really aimed at creating places that are safer and well-connected for people of all ages and abilities to ride bikes.

Rebecca just issued a new article last week that outlines those criteria again for folks. [The piece is titled "What Makes a Good Bike Network".] It's really important for us to maintain consistent standards across all cities that we evaluate, no only in the U.S. but worldwide, to ensure that the data and the analysis is reliable for folks. We don't measure things like ridership as part of the program. And it's certainly not the only way to assess bikeability in cities. But we think it aligns very well with other proven standards like [National Association of City Transportation Officials'] Urban Street Design Guide and Urban Bikeway Design Guide.

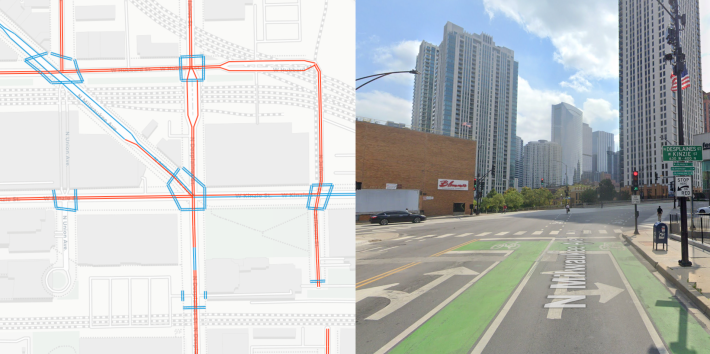

Hence, we know that Chicago's current score reflects some specific areas of need. Like we said, reducing vehicular speeds to 25 mph or lower to enhance safety. Really filling in gaps to create a complete bike network, particularly through intersections. If you zoom in on the Bikeway Network Analysis map for Chicago, you can see where the network is disconnected at points. At intersections where a bike lane disappears to make way for a right turn lane, or something like that. Those are gaps in the network that are lowering Chicago's score, because they're not able to create a complete connection through that intersection to the rest of the network.

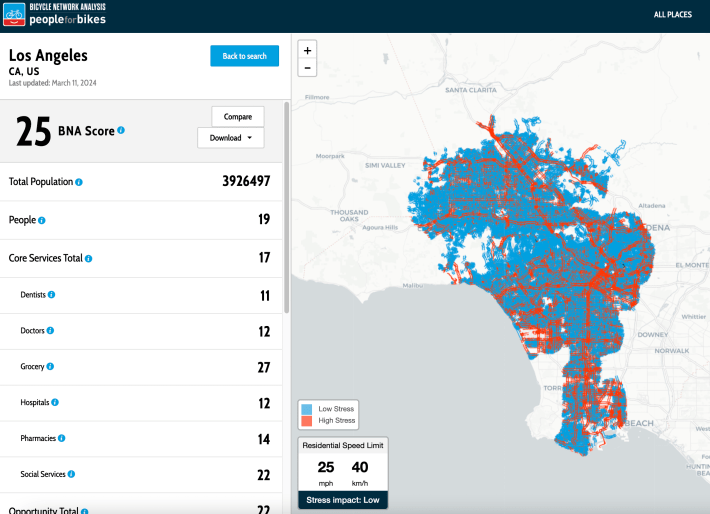

And I will say that Chicago's score has improved slightly, just over the last few years. But, I agree, it does fall behind a lot of other large U.S. cities. I think Chicago went from five points [out of 100] in 2020 to seven last year. So it's not moving backwards, but it's not comparable to places where we're seeing higher scores: Boston, Denver, Los Angeles, Milwaukee, New York, Washington D.C., Philadelphia.

JG: So your study is arguing that Los Angeles is a better place to ride a bike than Chicago?

MH: Our city rating program evaluates the quality of a city's low-stress bike network.

JG: What is the difference between how LA is doing its low-stress bike network and how Chicago is?

While Chicago got seven out of 100 points for its Network Score in 2023, Los Angeles got 19 points. And while Chicago's Bike Network Analysis number was nine, LA's was 25. Compare the mostly blue ["Low Stress"] map of LA below to the almost entirely red "High Stress" map of Chicago above. The main difference appears to be that while Chicago has a 30 mph default for residential streets, LA's default is 25.

MH: Los Angeles might not be the best example. They're certainly not the best place in the country.

So I would suggest looking, perhaps, at a place like Denver [Network Score of 42, or even Austin [Network Score of 31], where they really are focused on that network connectivity. They have slower speeds. They're looking at connections through intersections, building protected intersections, critically, to help folks get through those intersections. We know that's where things can easily fall a lot for bike networks. There's a lot of pressure at intersections. That's also where we see some of the biggest safety concerts.

So the cities that are scoring really well in our City Ratings are the ones that have lowered their speeds, not only in through speed limits but through actual design interventions to create slower streets, and places that are filling in gaps in the network to create those complete bike networks.

So, I agree, it's very encouraging to see this increase in bike ridership in Chicago. It clearly is showing that there's an interest in bikes as a mode of transportation in the city. And what we know is that that will only grow as the city builds more protected bike lanes, and fills in those gaps in the network, and reduces speeds.

We know, from studies that have been done for many years throughout the country, that complete bike networks and safer speeds help more people feel more comfortable riding bikes. So I feel pretty confident saying that with those kinds of improvements building over time, that Chicago really has this incredible potential to be one of the best places for biking in the U.S.

JG: Well according to this recent report, we had the most increase in biking of any of the ten largest U.S. cities. Isn't there kind of a disconnect between Chicago getting the highest ranking in one study, and one of the very lowest ratings in your study?

MH: I think it's really inspiring to think about what the ridership would be in Chicago if it had a better bike network. [Laughs.] It's phenomenal that people are persisting and ridership is growing without a perfect bike network. But we know that with a really great bike network, that ridership is going to grow even more.

JG: Were there any major changes to how the analysis was done this year?

MH: There weren't any major changes this year. We are currently considering some minor adjustments to how we integrate level of traffic stress onto streets, to make sure that we're really consistently aligned with some of the latest guidance that's come out through NACTO's latest bikeway design guide. That factors in things like the number of vehicular travel lanes on the street relative to the speed [that's often a big difference between otherwise analogous roadways in Chicago and LA], and what kind of bicycle facility is required on those streets.

So we are looking at some minor modifications to level of stress, potentially in next year's program. But I don't anticipate seeing any major changes in this year's program, in terms of how we do the analysis.

JG: OK, I think I pretty much know what's happening. It sounds like there's going to be another very low rating for Chicago this year based on the criteria that you've been using.

Thanks for taking the time to talk with me. I think I have a better understanding of the situation now.

MH: Yeah, of course. [Let me know] if you want to chat with any of the folks on our team post-June 25, once the ratings come out.

This year we're also going to be releasing historic data from the Bicycle Network Analysis, so cities will be able to see how their scores have changed over time, over the past several years, and how that compares to how other cities' scores have changed over time. So we think that we'll be something that folks will be really excited to see because historically we haven't published that data, but we've had it internally.

JG: All right, sounds good. Thanks again for your time.

MH: We appreciate your interest in the program, and thanks for encouraging people to check it out.

Did you appreciate this post? Please consider making a tax-deductible donation to support Streetsblog Chicago's paywall-free sustainable transportation reporting and advocacy.