Another year, another flawed report from the advocacy group People for Bikes rating Chicago as one of the very worst big American cities for biking.

For at least the third year in a row, the organization has ranked Chicago near the bottom of all large U.S. cities in its annual Best Places to Bike Report. This year our city scored a mere 7 out of 100 possible points, and 67th place out 69 slots. We were also ranked 161st out of 163 big cities around the world.

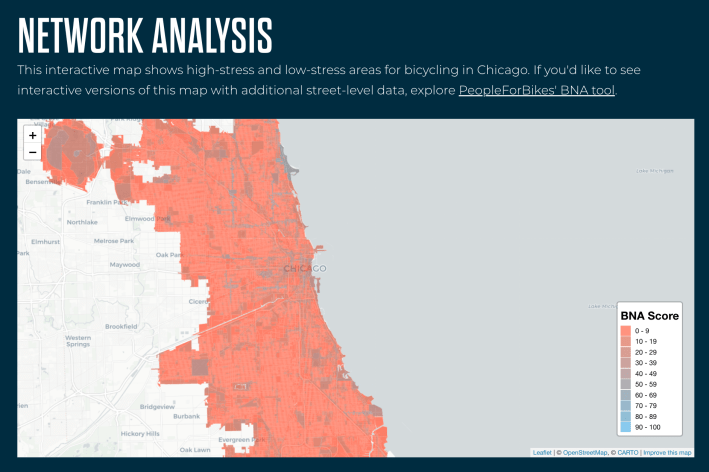

PFB City Ratings program director Rebecca Davies told Streetsblog a year ago that Chicago's terrible ratings are due to two factors: our city's default 30 mph speed limit and lack of a connected low-stress bike network. Davies said simply lowering the standard speed limit to 25 mph would put our city in the top 15 of large U.S. cities.

Davies is right that Chicago's relatively high speed limit, and not-always-cohesive and sometimes stressful bikeways, need improvement – more on that later. And I have no issues with PFB's assessment this year that Minneapolis (1st place), San Francisco (2nd), and Seattle (3rd) are the best large American cities for cycling, significantly safer and more comfortable to ride in than ours.

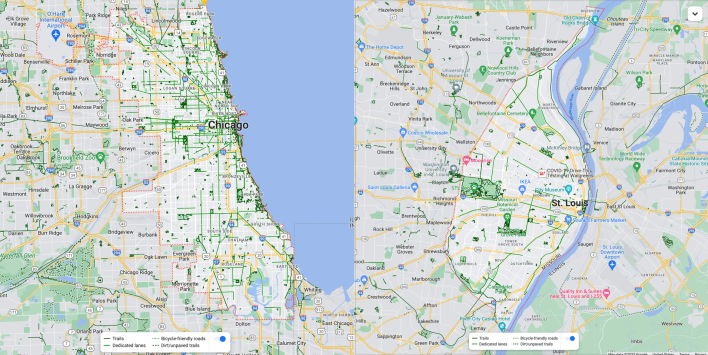

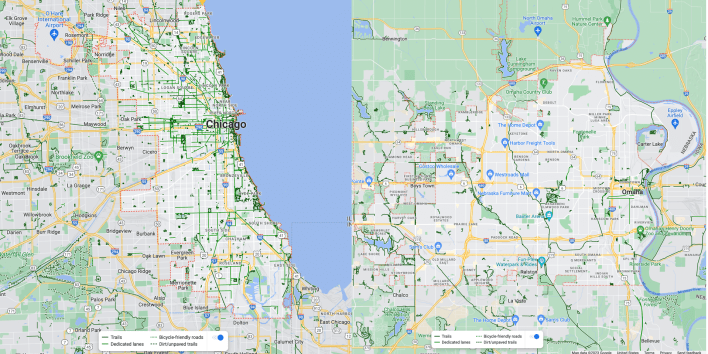

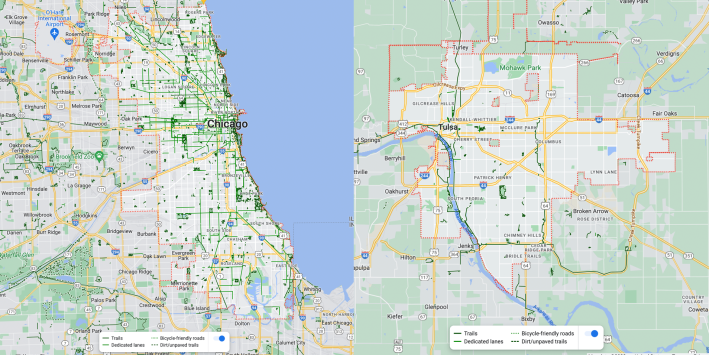

What I do have a problem with is PFB consistently rating Chicago far below way more car-centric large U.S. cities. These "superior" biking towns typically have relatively few or almost no bikeways. Again, Chicago, population 2.7 million, is in 67th place out of 69 large U.S. cities rated.

Saint Louis, population 302,787, is in 16th place for large American cities.

Omaha, population 488,059, is in 20th place for large American cities.

And Tulsa, population 410,652, is in 35th place, 32 spots above Chicago, despite the fact the Oklahoma city nicknamed the "Oil Capital of the World" is almost devoid of bikeways.

Obviously Chicago is an imperfect cycling city with lots of room for improvement. But what the PFB fails to acknowledge is that our city has put a significant amount of money and effort into improving bike infrastructure, certainly more per capita than many of the car-focused towns that got exponentially higher point scores. Here's are a couple of the reasons why, contrary to what you'd gather from the report, Chicago is already a non-awful big American city for biking.

• According to the Chicago Department of Transportation, we currently have over 430 miles of bikeways, including nearly 40 miles of protected bike lanes, more than 40 miles of Neighborhood Greenway side street bike routes, and 55 miles of off-street trails. The latter include landmarks all over the city including the Calumet Trail, the Major Taylor Trail, The 606, The 312 RiverRun, the North Branch Trail, and the 18.5-mile Lakefront Trail, a key commuting route to downtown that recently got separate paths for people on foot and wheels. CDOT says that over the past four years, the bike network has increased by over 30 percent.

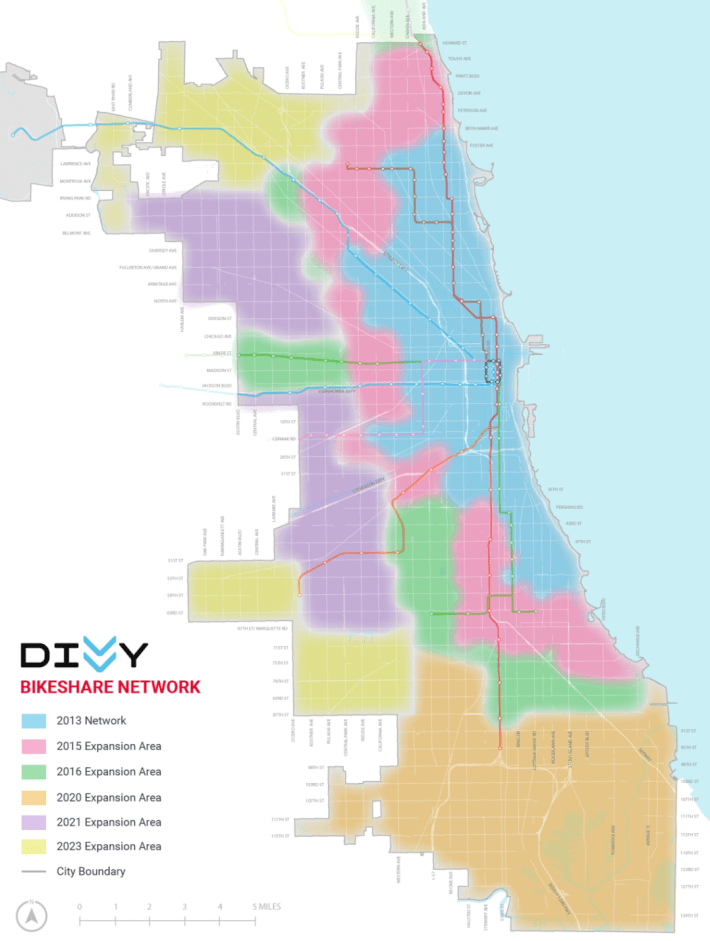

• The Divvy bike-share system currently has more than 800 stations, and over 15,000 (mostly) bikes and scooters, and by the end of this year it's slated to serve the entire city. Some of the cities ranked far above Chicago don't have bike-share at all. According to CDOT there are currently about 8,000 participants in the Divvy for Everyone program, which offers $5 memberships to low-income residents.

For these reasons, Chicago has been described as one of the best big American cities for bike infrastructure by the League of American Bicyclists' recent Benchmarking Bike Networks study. And in 2019 Bicycling magazine rated Chicago as the number-one U.S. biking city, although at the time I noted that that was a little overboard.

And even if we had no bike infrastructure at all, Chicago would still be a non-terrible place to ride thanks to our relentless street grid. This includes many bikeable residential streets like Leavitt Street north of Diversey Parkway, which is currently a fairly mellow northbound cycling route for miles, despite having no bike lanes. CDOT plans to improve it this summer by adding southbound contrafow bike lanes and speed humps. (Granted, some advocates have noted there should also be traffic diverters, infrastructure that prevents drivers from using side streets as "cut-through" alternatives to arterials for crosstown trips.)

But like just about every other reasonably chill residential street in Chicago, PFB rates Leavitt as a "high-stress" route because it has the city's default 30 mph speed limit. (Interestingly their Network Analysis map of Chicago identifies O'Hare and Midway airports as fairly comfortable places to ride a bike.)

PFBs description of Chicago as a horrible place for cycling isn't just annoying. It probably does some harm.

"While I wish the speeds were lower, this report could discourage people from trying to bike in Chicago at all," tweeted former Chicago Tribune transportation columnist Mary Wisniewski. "That's a shame – biking here is one of the great pleasures of my life, despite frequent aggravation with driver behavior. And more bikers means more safety."

On the other hand, there are some positive aspects to having a national advocacy group say your city's bike network is garbage due to higher speed limits and a sometimes spotty bikeway layout.

Eight people were killed by drivers while riding bikes in Chicago last year. If Chicago was to lower its default our speed limit from 30 mph, it would surely prevent some serious injuries and deaths. Federal studies show that a vulnerable road user struck at 30 mph has a 45 percent chance of dying. But at 20 mph the percentage drops to only 5 percent.

In new Chicago mayor Brandon Johnson's recent transition report, the transportation committee section, heavily influenced by local bike advocates, recommends lowering the speed limit to 20 mph on arterials and 10 mph on side streets. It remains to be seen whether the mayor can pull that off, but a national study arguing our current 30 mph limit endangers bike riders can't hurt the cause.

And, as I've written in depth before, while it's great that Chicago has hundreds of miles of bikeways, there are lots of gaps in the system, especially on the South and West sides. That's partly due to aldermanic prerogative, the de-facto ability of City Council members to veto projects like bicycle lanes in their wards. These politicians often worry about new bikeways upsetting constituents who drive. But If we want to make Chicago a safer and more comfortable place to bike for people of all ages and abilities, we need to build a citywide, connected, protected bike lane network ASAP.

So while PFB's report that Chicago biking is atrocious is only half true, it's good that it provides ammunition for local advocates to complain about our city's speed limit and bikeway gaps. Hopefully that will light a fire under the mayor, the City Council, and CDOT to do more things, faster, to solve these problems. Here are a few examples of that phenomenon.

"Our speed limits and our laws reflect our values,” Chicago, Bike Grid Now! cofounder Rony Islam recently told Block Club in response to the PFB study. “When we have laws that say it’s OK for cars to drive 30 miles per hour next to a bike in a painted bike lane that’s in the door zone of parked cars, I think that’s a reflection of what we think is important in our city."

Equiticity founder Oboi Reed recently said to Axios that he's optimistic that the report will spur local officials to "do more and invest more to make our city more bikeable, especially in Black and Brown communities."

"While the city has invested millions of dollars building dozens of miles of protected bike lanes over the past ten years, the lack of seamless connections among these safe and comfortable bikeways is a barrier for many people who would otherwise use bikes as everyday transportation," noted Active Transportation Alliance advocacy director Jim Merrell in a blog post yesterday.

"Chicago ranks [161st] out of 163 [global] big cities for biking," tweeted bike injury attorney Brendan Kevenides (a Streetsblog Chicago sponsor.) "There's your wakeup call CDOT. Enough half measures. Enough gaps in our bike ways. Build a protected, comprehensive bike grid for our city now!"

So I find it irritating that People For Bikes says Chicago is a much worse place to bike than Phoenix or Jacksonville. But even I will acknowledge it's good that a national advocacy group says Chicago needs to get serious about lowering speed limits and creating a citywide protected bike network. We do.

Read the 2023 People For Bikes Best Places to Bike report here.

View PFB's 2023 city rankings here.

Dd you appreciate this post? Please consider making a tax-deductible donation.