People for Bikes' City Rating declared Chicago to be one of the worst large cities in the U.S. for biking in its 2021 City Ratings report, but the League of American Bicyclists held our city up as a case study for best practices in its new Benchmarking Bike Networks study. Streetsblog will look at both of these assessments in two different posts this week. Read our writeup of the League report here.

Last July I was annoyed when the Colorado-based nonprofit People For Bikes issued its annual City Ratings report that evaluates the bicycle-friendliness of over 700 cities worldwide, and Chicago was ranked in in the bottom 5 percent of large cities, behind dozens of other U.S. cities that are more car-centric than ours, and/or have way-lower bike mode share.

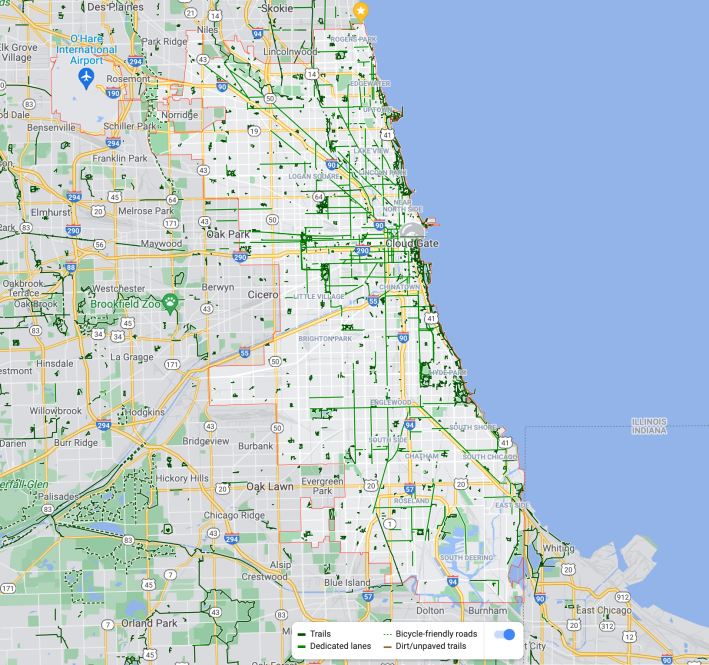

How could it be possible, I wondered, that Chicago, which has a cycling-friendly street grid, hundreds of miles of bike lanes (including dozens of miles of protected lanes), and a nearly-citywide bike-share network with about 13,000 public cycles, was ranked in 99th place out of 104 large cities worldwide?

Sure, our city has plenty of warts when it comes to bikeability. But is it really worse here than places like Dallas (97th place), Houston (93rd), Memphis (88th), Oklahoma City (73rd), Atlanta (68th), Los Angeles (58th), Phoenix (56th), and St. Louis (51st)?

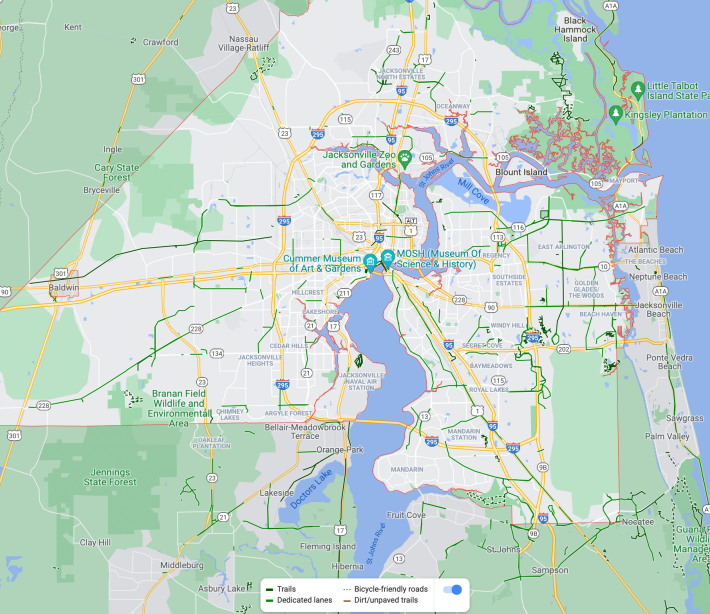

Particularly baffling to me was the relatively high 83rd place ranking of Jacksonville, Florida, which has less than a third of Chicago's 1.7 percent bike mode share (the percentage of commuters who primarily get to work by bike) at only 0.5 percent as of 2019, and about six times the bike fatality rate.

For example, @peopleforbikes ranked Chicago 16 places behind, Jacksonville, FL, pop. 890,467, a city with no rapid transit and the second-lowest population density of any large U.S. city. It's basically a worst-case scenario of car-centric sprawl, with relatively few bikeways. pic.twitter.com/wjQIne9btN

— John Greenfield (@greenfieldjohn) July 20, 2021

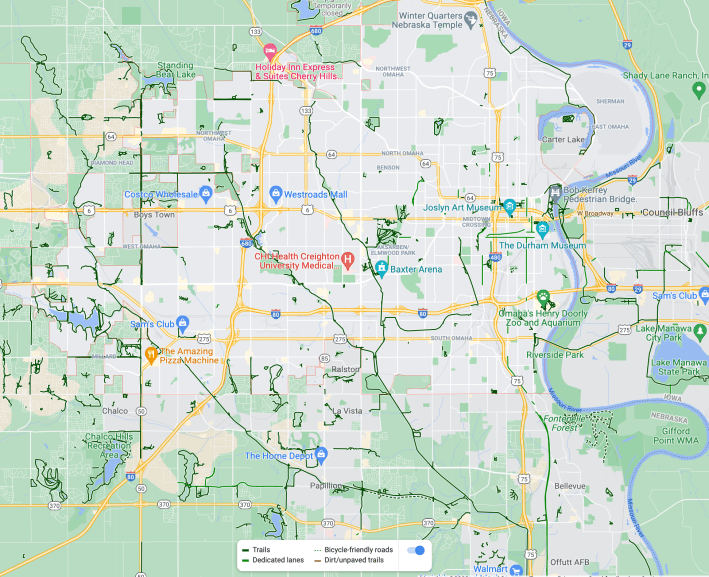

And then there was Omaha, Nebraska, in 54th place, a full 45 spots ahead of Chicago, despite the fact that Omaha had a measly 0.3 percent bike mode share as of 2019, or less than one-fifth that of Chicago.

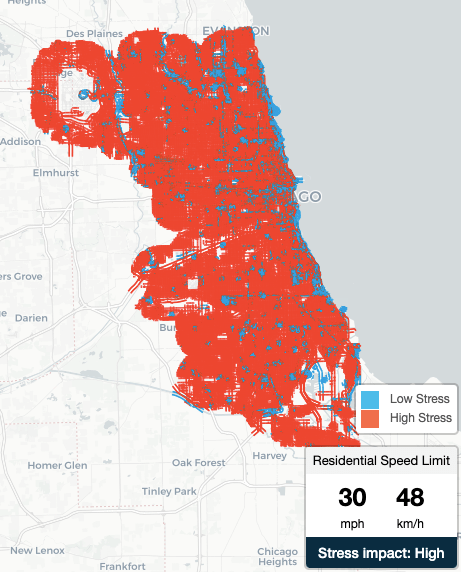

Kyle Wagenschutz, vice president of local innovation at PFB, explained that Chicago scored an abysmal 16 out 100 points under the group's overall rating system, which is based on the safety and connectivity of the bike network and survey feedback, largely due to our city's default 30 mph speed limit, and just-OK bikeway connectivity. Classifying every Chicago roadway, including quiet side streets, as "high-stress" due to the speed limit doesn't make a lot of sense to me. But Wagenschultz said that if we lowered the speed limit to 25, our city's Bike Network Analysis score would increase from a pitiful 5 out of 100 possible points, to a more respectable 37.

But why the heck did People for Bikes give much higher city ratings to Jacksonville and Omaha – car-focused towns with little on-street bike infrastructure, where almost no one cycles to work – much higher rankings than Chicago?

Wagenschutz referred me to Rebecca Davies, PFB's bicycle networks data manager, who runs the group's Bicycle Network Analysis tool, and Davies shared some thoughts behind the BNA scores for Chicago (5), Jacksonville (16), and Omaha (31).

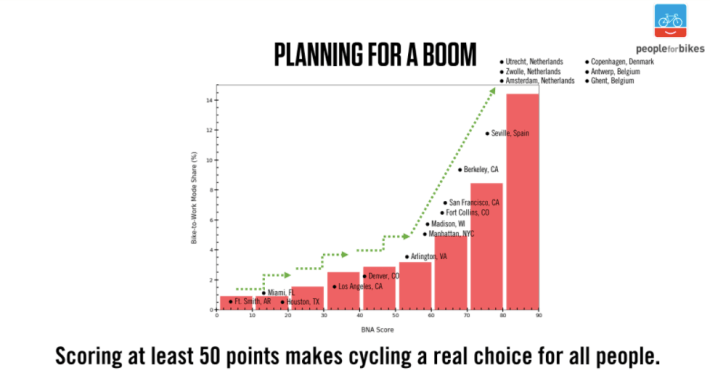

Davies said there's not that much difference between the bikeability of cities at relatively low BNA levels like these. "In the BNA, scores of 5, 16, and 31 are not as different as scores of 55, 66 and 81 even though their numerical difference is the same. Differences in low scores are less important because the relationship between good infrastructure and ridership is roughly exponential. At BNA scores under 50, most people still feel unsafe bicycling regardless of whether the BNA score is 10 or 30. Improving a score from 50, to 60, to 70 produces gains with a much larger marginal value because the network approaches the point at which people of all ages and abilities, including children and the elderly, view bicycling as a safe, efficient option."

Davis said this trend is seen most clearly in cities like Paris, France, and Seville, Spain, where the rapid deployment of a cohesive bike network led to fast increases in ridership. "Building one protected bike lane is not going to produce sharp changes. Building a protected lane network can produce a sharp change."

"All three cities lack connected bike infrastructure and have large swaths of the city that have no access to dedicated bicycling facilities," Davies added. "Higher speed limits and more lanes of motor vehicle traffic require greater separation of bikes and motor vehicles. Most low-scoring cities do not sufficiently separate bikes from motor vehicles, which is true of Chicago, Jacksonville, Omaha, and every other large city in the U.S. – even higher scoring cities like Seattle, San Francisco, and Brooklyn have a long way to go." (Amusingly, the PFB report refers to each of New York's five boroughs as a "city.")

While it's true Chicago needs way more protected bike lanes across the entire city to separate bike riders from drivers, it seems odd to put us in the same category in that regard as Jacksonville and Omaha. While our city had 26.7 miles of protected lanes at the start of 2021, with plans to add 12 more miles in 2021-22, Jacksonville and Omaha had few or none at the start of last year.

Davies acknowledged that Jacksonville has fewer on-street bikes lanes than Chicago, and the connectivity is worse. "Jacksonville’s bike network is limited to a handful of painted bike lanes and protected bike lanes. Few of these stretches of infrastructure connect, which results in a low score. Many of the painted bike lanes provide inadequate separation of bikes from fast-moving motor vehicle traffic." When you factor in that Jacksonville has the same 30 mph default speed limit as Chicago, it's even weirder that the Florida city got a higher Bike Network Analysis score than Chicago.

Davies also admitted that Omaha has few on-street bike lanes of any kind, but said the city got points for its off-streets paths. "While the network is insufficient to facilitate travel throughout the city, the paths are well connected in the western portion of the city, creating a continuous region of low-stress connectivity." Omaha also has a default 25 mph speed limit, although it's unclear whether that actually results in slower average speeds on that city's residential streets than on Chicago's side streets with 30 mph speed limits. But, obviously, lowering Chicago's default speed limit to 25, or even 20 mph, could only improve traffic safety.

"Chicago has more varied types of bike infrastructure than Omaha or Jacksonville," Davies acknowledged. "The infrastructure is concentrated in the eastern half of the city. However, the network is fragmented and many of the bike lanes are unprotected lanes that, as in Jacksonville, do not sufficiently separate bikes from cars. Some of the unprotected lanes are buffered, but it is still not sufficient separation given existing conditions on those roads – physical separation is necessary. Also, many of the [bike lane corridors] have large gaps where the lane disappears temporarily. While Chicago has more intermittent infrastructure than the other two cities, the BNA does not reward trips that are partially safe. Trips must be 100-percent safe to receive any points."

Well, sure, if People for Bikes defines any bike trip that's not on an off-street trail, a sub-30 mph residential street, or a main street route that has protected bike lanes on the entire route "unsafe," I suppose they can argue that Omaha has a higher percentage of "safe" routes than Chicago. That's despite the fact that fewer than one in 300 residents bikes to work in the Nebraska city, partly because it has no on-street bikeway network, and exactly one protected bike lane street.

But even using PFB's rules, arguing that biking is "safer" in Jacksonville than Chicago is simply nonsensical.

Another perverse aspect of the People for Bikes rating is that Chicago's relentless street grid – which is a very good thing for biking because it provides more options for routes on quiet side streets than exist in a less-grid-oriented city like Jacksonville – actually contributed to our low Bike Network Analysis score.

"[Without taking into account residential speed limits] Chicago has the strongest bike network based on the remaining factors, which is likely due to the presence of more... dedicated bike infrastructure and an efficient city street grid design," Davies acknowledged. "In other words, residential streets play a bigger role in Chicago's network score and thus [30 mph] residential street speeds depress the city's score more."

I'm sorry, but a bike-friendliness rating system where a city gets penalized for having a bike-friendly grid makes zero sense. People for Bikes really needs to fix that problem the next time they do City Ratings.

OK, now that I've got that out of my system, let's acknowledge the more important takeaways from the PFB report, although most of this is already familiar to Chicago bike advocates, with no number-crunching needed. Davies wrote:

For Chicago, Omaha, Jacksonville, and most U.S. cities, [the Bike Network Analysis] tells us:- There is not enough dedicated bike infrastructure to make bicycling an appealing and convenient option for the average person.- Speed limits on streets where bikes and cars mix are too high.- Existing bike infrastructure is often insufficient given other road conditions (speed, number of motor vehicle travel lanes, intensity of use.)- More safe street crossings are needed.

Although part of the BNA’s value is enabling comparisons across many cities, we encourage cities to compare themselves to cities that are aspirational models of great bicycling and identify how those concepts can be applied locally. For Chicago, domestic cities like Seattle, San Francisco, and Brooklyn are better models than Jacksonville or Omaha. We added international cities to the analysis because there are no large world-class cities for bikes in the U.S. International cities like [formerly car-centric] Paris or Rotterdam are even better aspirational models for Chicago and its U.S. peers.

So, yes, Chicago got screwed by People for Bikes' flawed rating system, and it was inaccurate for them to say this is one of the worst large U.S. cities for biking, when it's actually one of the better ones. But the larger truth is that American standards for bike-friendly cities are depressingly low. So Chicago really needs to take action to make transportation cycling as safe, enjoyable, and normalized as it is in truly great cycling cities in other parts of the world.