Glass-half-full Bike League report highlights Chicago’s successes in promoting cycling

8:41 PM CST on January 28, 2022

Biking on 55th Street in Chicago’s Hyde Park neighborhood. Photo: Steven Lucy

Last July, People for Bikes’ City Rating declared Chicago to be one of the worst large cities in the U.S. for biking in its 2021 City Ratings report. However, the League of American Bicyclists held our city up as a case study for best practices in its new Benchmarking Bike Networks study. Streetsblog Chicago is looking at both of these assessments this week. Read our writeup of the People for Bikes report here.

Is biking in Chicago awful, awesome, or somewhere in between?

While the Colorado-based nonprofit People for Bikes rated Chicago in 99th place for bikeability among 104 large cities around the world, including dozens of more car-centric U.S. cities, the Washington, D.C.-based League of American Bicyclists advocacy group had a relatively rose-colored take on our city in its new report “Benchmarking Bike Networks.”

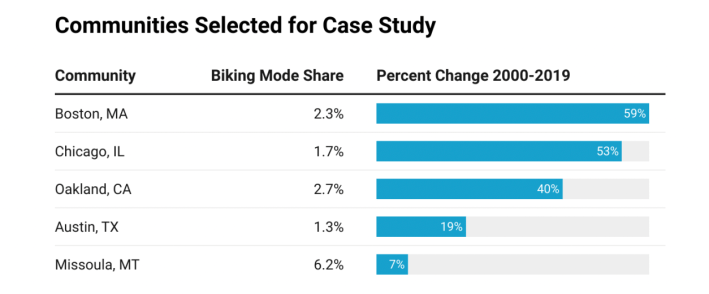

The League argues that Chicago is a success story in terms of infrastructure and policy initiatives to help get more people to ride. The study says that, along with Boston, Austin, Oakland, and Missoula, Chicago is one of the U.S. cities "where bicycle commuting has increased the most over the last decade," thanks in part to "areas where they have built connected [bikeway] networks."

While U.S. bike mode share (the percentage of commuters who get to work primarily by bike) is currently a dismal 0.5 percent, all five cities LAB discussed are at at least twice that level. Chicago's mode share is currently 1.7 percent, only about a quarter of that in Portland, Oregon, and a world away from cycling capitals like Amsterdam and Copenhagen, where about one in three trips of any kind is made by bike. However, the League notes that Chicago's current mode share represents represents a 53 percent increase from 2000.

“Benchmarking shows what really good communities [emphasis added] are doing and what others can do so that we’re all pushing towards the same goal of safe bike networks that are accessible to everyone,” League policy director Ken McLeod, the told Bloomberg City Lab. Like the People for Bikes study, the LAB report emphasizes the importance of citywide networks of connected bike lanes, and notes that high-quality physically protected bikeways are crucial for making cycling safe and comfortable on streets with high traffic volumes and speeds.

Let's take a look at what LAB had to say about the state of Chicago biking in its case study of our city. Many of the talking points came directly from conversations with Chicago Department of Transportation staff. So while yesterday's discussion of People for Bikes' dismal assessment of Windy City biking had a rather defensive tone, in contrast my commentary here will include some reality checks on CDOT's depictions of its own projects.

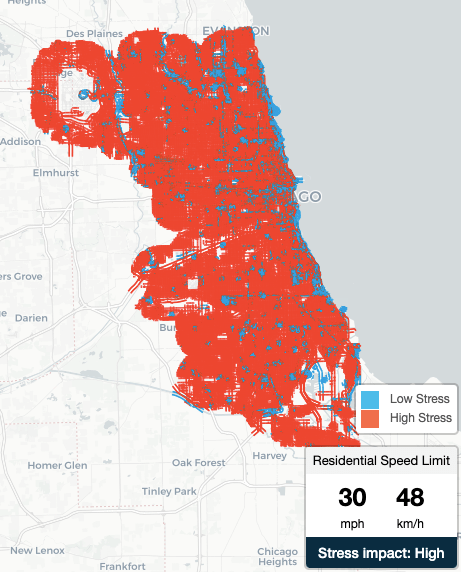

One big difference between the People for Bikes and the League study is the way Chicago's relentless street grid was interpreted. A PFB staffer admitted to me that the group's ratings inadvertently penalized Chicago for its grid, which provides lots of options for bike routes on low-traffic residential roadways. That's because PFB's Bicycle Network Analysis system rates any street with without bikeways and a 30 mph speed limit as "unsafe" for cycling, Chicago's default speed limit is 30, and the grid means we have tons of quiet, bikeable side streets that the algorithm dubiously classified as "high stress," as you can see in the map above.

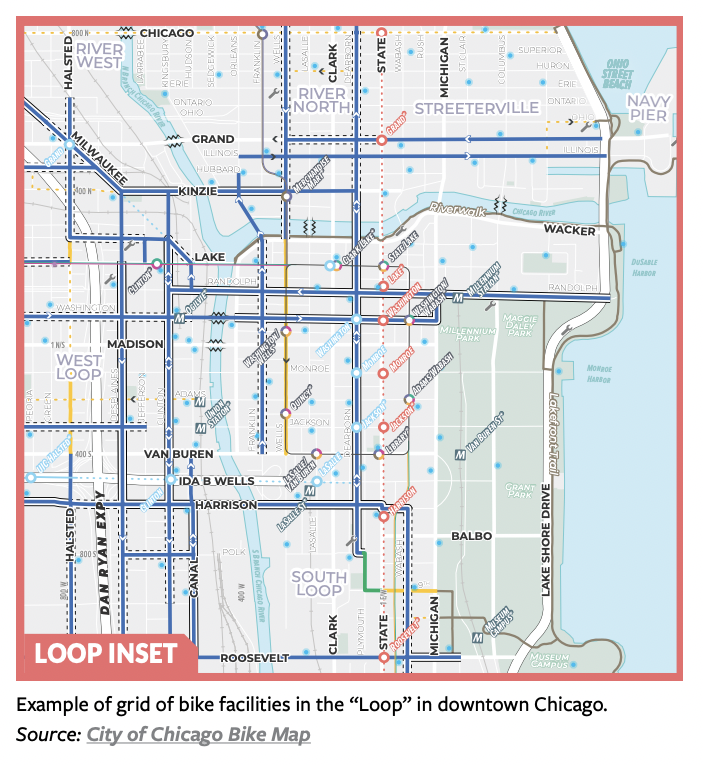

However, the League didn't make that mistake. It noted that Chicago's "gridded network of streets is an asset [emphasis added] when building a bike network, and grids of bike facilities... appeared to be more common than in other cities reviewed for this report."

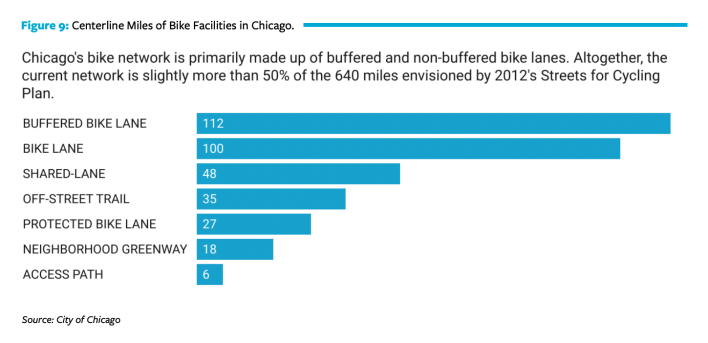

Now onto the reality check part. The League credits the Chicago Streets for Cycling Plan 2020, released in 2013, with helping Chicago roughly double its bikeway mileage over the last 10 years. However, that document was arguably a failure, since it called for building a 645-mile bike network by 2020, but our city still only had about 350 miles of bikeways as of October 2021.

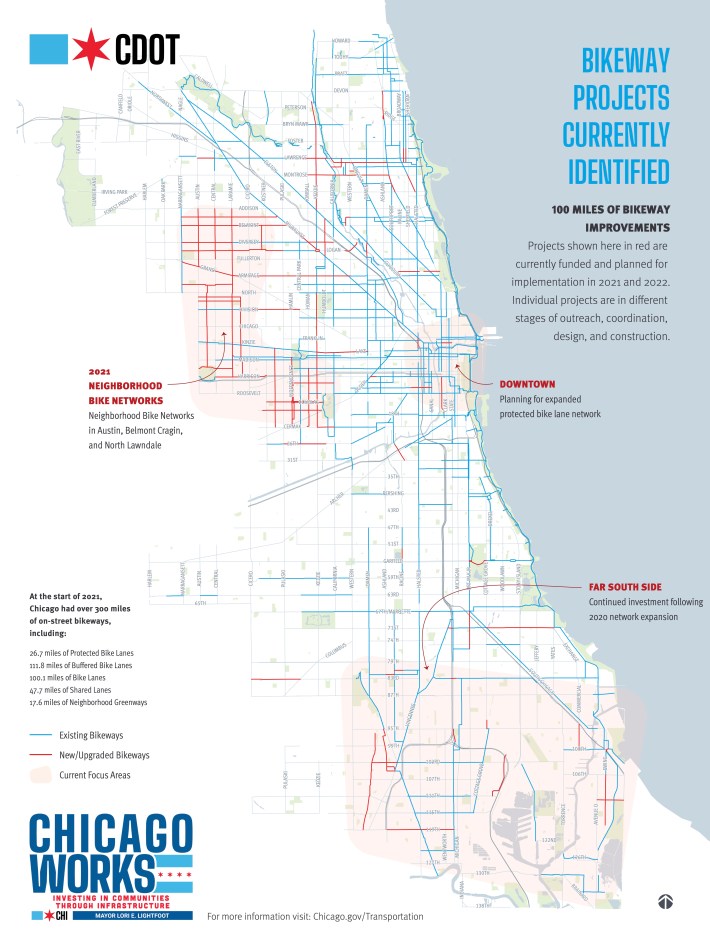

The League notes that last September CDOT announced a goal to install a total of 100 miles of miles of new and upgraded bikeways in 2021-22. But local advocacy groups like the Active Transportation Alliance noted that the current plan is too scattershot, without enough emphasis on building a cohesive system of physically protected bike lanes, where people of all abilities might feel comfortable riding. “We need to connect the network, build more protected lanes, and engage community members so they’re not fighting these projects," said ATA executive director Amy Rynell. "We need to build political will so we don’t just wind up with a patchwork, like we have now.”

LAB also highlights one of the transportation department's more effective recent approaches, using a saturation strategy in the Austin, Belmont Cragin, and North Lawndale communities, which were the focus of this year’s Divvy bike-share expansion, crisscrossing these communities with 45 miles of bikeways, incorporating input from local community members. Oboi Reed, leader of the mobility justice group Equiticity, told me last year he appreciated the plan’s “targeted focus on primarily Black and Brown neighborhoods where cycling and bicycles are needed the most.”

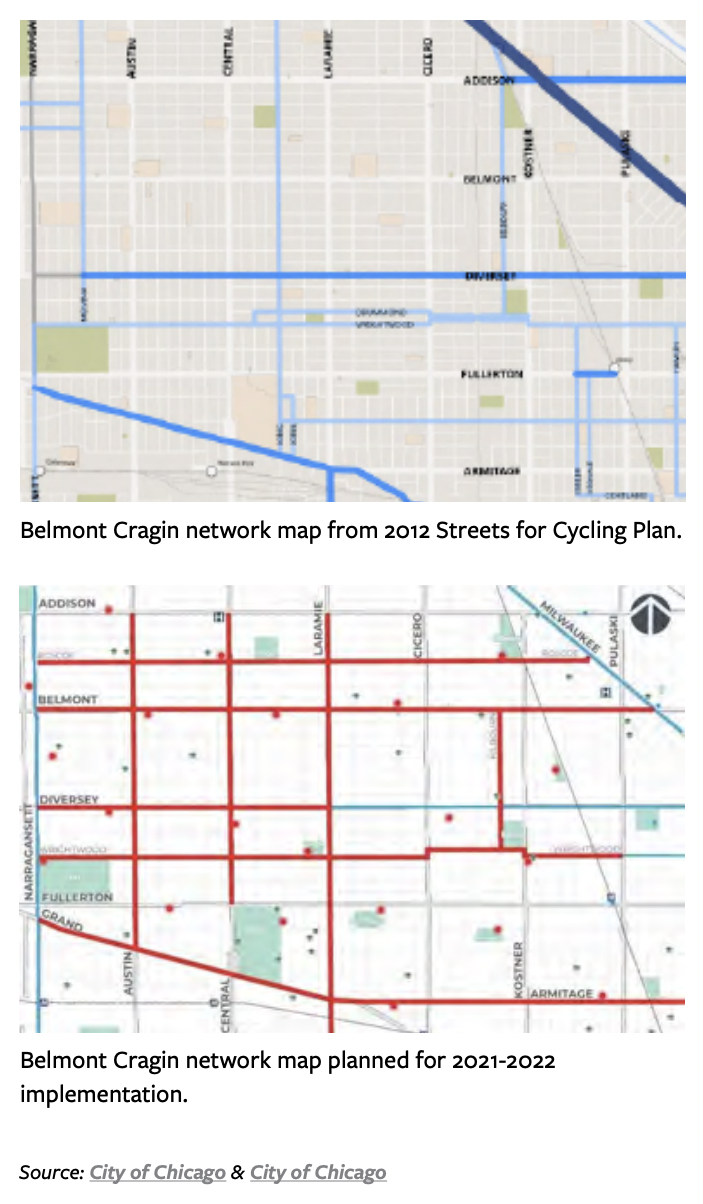

The League's discussion with CDOT staff focused on the department's efforts in Belmont Cragin, a predominantly Latino Northwest Side community, which LAB called "leading with collaboration," including partnerships with organizations like the Northwest Side Housing Center (now the Northwest Center) and its youth council, Bikes N' Roses bike education center, and the Consortium to Lower Obesity in Chicago's Children to help tailor the new local bike network to community members' needs.

CDOT told the League that this approach led to creating more miles of bikeways in Belmont Cragin than were proposed in in the Streets for Cycling plan. Interestingly, LAB says that while most cities would be updating their bike plan after a decade, "city staff told us that continuous neighborhood network planning in Chicago may remove the need for such a large formal update."

Judging from the fact that writing Streets for Cycling was a labor-intensive process involving lots of community meetings across the city, which yielded underwhelming results, perhaps CDOT is correct that doing that exercise all over again would be a waste of time. The hyperlocal Belmont Cragin planning model may be a more productive approach.

The League also spotlighted Chicago's Vision Zero Downtown Action Plan's call to “lower the speed limit [from 30 mph] to 20 mph across downtown.” The plan notes that Seattle saw one-fifth fewer severe crashes after lowering the speed limit in its central business district. This would be a great thing (and would raise Chicago's People for Bikes rating), but may be easier said than done due to existing Illinois legislation that restricts the power of municipalities to lower speed limits below 30, and pushback from local residents. But Streetsblog will definitely advocate for that lower sped limit moving forward.

In addition, LAB highlighted the fact that Chicago owns the extensive Divvy public bikes system, rather than having a patchwork of privately bike-share services. Moreover, the League noted, the city has kept a tight reign of scooters, holding multiple pilot programs before finally approving a permanent program for this year. "These efforts have provided the city a larger degree of control over shared bikes and scooters than some cities, and also made those efforts more integrated in the city’s planning." Of course, some would argue the downside of this approach is that Chicagoans have had to wait years for permanent access to scooter-share.

So the League's description of Chicago bike initiatives is a bit sunnier than the reality, reflecting the fact that their info came largely from city officials. But LAB did a good job of laying out some of the things that CDOT has gotten right when promoting cycling, which other cities would do well to emulate, while noting that Chicago still needs a lot more miles of protected bike lanes. That's a much more constructive approach than People for Bikes announcing to the world that our city is a horrible place to ride.

In addition to editing Streetsblog Chicago, John writes about transportation and other topics for additional local publications. A Chicagoan since 1989, he enjoys exploring the city on foot, bike, bus, and 'L' train.

Stay in touch

Sign up for our free newsletter

More from Streetsblog Chicago

Which Metra corridor would become more bike-friendly and greener under a new plan? Ravenswood!

Thanks to plans to convert little-used parking spaces, the avenue is slated to get a new bike lane, and the Winnslie Parkway path and garden will be extended south.

They can drive 25: At committee meeting residents, panelist support lowering Chicago’s default speed limit

While there's no ordinance yet, the next steps are to draft one, take a committee vote and, if it passes, put it before the full City Council.

One agency to rule them all: Advocates are cautiously optimistic about proposed bill to combine the 4 Chicago area transit bureaus

The Active Transportation Alliance, Commuters Take Action, and Equiticity weigh in on the proposed legislation.