When it comes to lowering Chicago's default speed limit from 30 to 25 mph to save lives and money, the City Council is finally starting to put the pedal to the metal, so to speak. Yesterday the Committee on Pedestrian and Traffic Safety met to discuss enacting this safe streets policy, which has already reaped huge benefits for peer cities like New York.

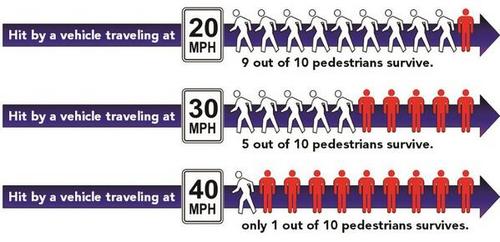

During the public comment period that kicked off the hearing, several speakers voiced support for lowering the speed limit. Micheal Podgers, policy lead at the grassroots advocacy group Better Streets Chicago, was typical of the supporters. "Lower speed limits are good. We know that speed is a major contributor to whether somebody who is hit by a [driver] is killed or not."

Podgers added that, like the Active Transportation Alliance and the mobility justice organization Equiticity, Better Streets wants to see lower posted numbers coincide with ambitious street redesigns that calm traffic. "Speed limit reduction... needs to be matched with robust funding and robust support for actually building up the infrastructure that is going to guide driver behavior towards safe choices." Such projects could include "road diet" lane reductions, sidewalk extensions, speed humps, raised crosswalks, and protected bike lanes.

At the meeting Morgan Madderom, director of transportation policy and planning for the committee, explained that the type of legislation the committee sees most frequently is routine matters. These include putting up a stop sign, designating a disabled parking spot, or changing the speed limit for a single block or stretch of blocks. For better or worse, the local alderperson is usually left to make decisions about traffic safety in their ward.

"Since routine legislation usually doesn’t affect alders outside of the ward that it is being enacted in, other alders don’t have a strong reason to oppose it," Madderom added. "When legislation is passed in our committee, it moves to the full City Council for a vote. Routine legislation is typically passed as an omnibus and items are not voted on individually. Non-routine legislative matters are often required to be passed by the relevant committee, and then are voted on and passed again by the full council. If the committee voted to reject a piece of legislation then it would not pass on to full council. The alder would have to reintroduce that piece of legislation again, if they wanted it to be reconsidered for a vote by the committee."

Committee Chair Ald. Daniel La Spata (1st), a traffic safety advocate, made it clear that after hearing from community members Wednesday, the alders were not immediately going to vote on lowering the speed limit. Instead, the purpose of yesterday's meeting was to begin the conversation. To jump-start the discussion, attendees heard from several expert panelists, such as Victoria Barrett, a senior transportation planner for the Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning, the region's metropolitan planning organization.

"It’s important to understand that the risks posed by the transportation system in the United States are higher than those in other developed countries," Barrett said. "When you consider traffic deaths in the generalized risk of fatality rate per population, the United States' rate is more than double that of Canada and Australia, and more than four times that of Sweden and the UK. Many of the countries included on this list have more stringent speed limit policies in urban areas."

Another panelists was Amy Rynell, executive director of Active Transportation Alliance, which has been a strong proponent for lowering the speed limit. She said her organization wants a city that is vibrant and climate resilient, with mobility choices that benefit all the neighborhoods in the city and allows citizens to get around safely.

Echoing earlier remarks by La Spata, Rynelle said that the goal of the 25 mph default is safety, not ticket revenue. "We need a policy in our city that values the ability of people of all ages and ability to get around safely. And lowering the speed limit is a key piece of that, but not as a revenue generator. We have been working really hard as a city to make our traffic enforcement process more equitable to address fines and fees and this is just another opportunity to dig into what is an equitable approach to community compatibility and traffic safety."

After the meeting La Spata said the committee does not have a firm timeline for voting on, let alone enacting, a new default speed limit. While the idea has gotten a favorable response, there's still no ordinance yet. So now the work is drafting the legislation, figuring out the schedule, and community engagement before and after the ordinance goes up for a vote.

Did you appreciate this post? Please consider making a tax-deductible donation to help Streetsblog Chicago keep publishing through 2025. Thank you.