There were many stirring moments during today’s inauguration of Lori Lightfoot as Chicago’s first Black female mayor, and the first openly gay person to run the city. However, her inaugural address had almost no transportation content, save for a brief reference to Chicago’s pension debt diverting money that could otherwise be used to “revitalize our transportation system.”

The most exciting thing in her speech from a walking, biking, and transit advocate’s perspective, was her promise to end Chicago’s longstanding de facto policy of aldermanic prerogative.

Aldermanic prerogative has allowed City Council members to treat their wards as a personal fiefdom by giving them the power to veto virtually any project within the district. In exchange for this perk, aldermen have rarely interfered with affairs in other wards, and under Richard M. Daley and Rahm Emanuel they’ve typically rubber-stamped the mayor’s big initiatives, going along to get along.

One of the major problems with aldermanic privilege is that it breeds abuse of power and corruption. When Council members have the ability to block everything from a request for a perpendicular storefront sign to a zoning change for a major development, it creates the temptation to shake down residents and businesses in legal and illegal ways.

It’s the norm for real estate developers to write fat checks to the local alderman’s campaign fund because they know it greases the skids for getting their projects approved. And a friend of mine who runs a green business incubator building once told me that while he despises the alderman in whose district the building stands, he always chips in a few thousand dollars to the politician’s reelection coffers because he knows that the politico can make his life difficult if he doesn’t. That’s a big reason why incumbents have had such an advantage in Chicago elections.

And, of course, powerful Finance Committee chair Ed Burke, a longtime Southwest Side alderman, was recently indicted by the feds for allegedly strong-arming a McDonald’s franchisee into making a large donation to Cook County board president Toni Preckwinkle’s mayoral election fund in exchange for a driveway permit.

“This requirement that people must give more to get access to basic city services must end,” said Lightfoot during her speech. “And it will end, starting today. Later this afternoon, I will sign an executive order to end the worst abuses of so-called aldermanic privilege.”

“This does not mean our aldermen won’t have power in their communities,” Lightfoot clarified. “It does not mean our aldermen won’t be able to make sure the streetlights are working …or the parking signs are in the right place …or any of the thousands of good things they do for people every day. It simply means ending their unilateral, unchecked control over on every single thing that goes on their wards. Alderman will have a voice, not a veto.”

Lightfoot made good on that promise later that afternoon, signing the document telling city departments to end aldermanic prerogative. Assuming Lightfoot’s effort to eradicate aldermanic veto power is successful, one obvious benefit will be removing a major barrier to addressing segregation in our city.

Traditionally, new affordable housing has mostly been built in low-income areas, which contributes to creating areas of concentrated poverty. Racist and classist resistance to building affordable housing in largely white, middle-class or affluent neighborhood is a major political force. It was a big factor in why pro-affordable-housing 45th Ward alderman John Arena lost reelection this year.

Meanwhile, when Alderman Anthony Napolitano in the neighboring 41st Ward invoked aldermanic privilege last year to block an affordable housing proposal, it was a popular move with many of the residents of his ward, heavily populated by white city workers and first responders. That probably helped him win reelection with a whopping 70 percent of the vote.

Now on to the subject of why dismantling aldermanic prerogative is good for sustainable transportation. While community input is crucial for successful and equitable projects, many of the best traffic safety initiatives involve a political lift. For example, whenever travel lanes or parking spots are converted to accommodate bus lanes, pedestrian infrastructure, or protected bike lanes, there’s bound to be some pushback from drivers.

Aldermen might be tempted to veto good projects in their wards because it’s the political path of least resistance. In some cases, their motives for putting the kybosh on a transit, walking, or transit project are completely inscrutable, but they’re successful in killing the initiative just the same.

The most notorious example of this abuse of power was in 2005 when the late 50th Ward alderman Berny Stone dug in his heels and refused to let the Chicago Department of Transportation build a fully-funded bike bridge over the North Shore Channel that he had previously approved. Stone gave various conflicting or nonsensical explanations for his opposition, but it wasn’t until after he lost reelection and passed away that the project finally moved forward. CDOT broke ground on the bridge in February, and it’s currently under construction.

Here are a few other more recent examples of City Council members using aldermanic privilege to block, downgrade, or delay sustainable transportation projects:

- In 2013, 24th Ward alderman Michael Chandler approved protected bike lanes on Independence Boulevard, and then ordered CDOT to convert them to buffered lanes after residents balked at the non-curbside parking configuration.

- Also in 2013, 42nd Ward alderman Brendan Reilly blocked CDOT from installing Divvy stations on the Magnificent Mile.

- In 2016, 5th Ward alderman Leslie Hairston and 8th Ward alderman Michelle Harris vetoed CDOT’s proposal to install protected bike lanes on Stony Island Avenue in their districts, arguing that they would cause traffic jams.

- In 2018, several aldermen on the Near North and South sides insisted that their wards be excluded from the Car2go car-sharing pilot area because they were worried about the impact on parking for private cars.

- In January, 3rd Ward alderman Pat Dowell tried to block the construction of an ‘L’ stop at 15th and Clark, and succeeded in forcing the developer who proposed it to relocate the facility.

- Earlier this month, 4th Ward alderman Sophia King finally allowed CDOT to start building bike improvements in the South Loop after delaying the project for a year due to her focus on maximizing car parking.

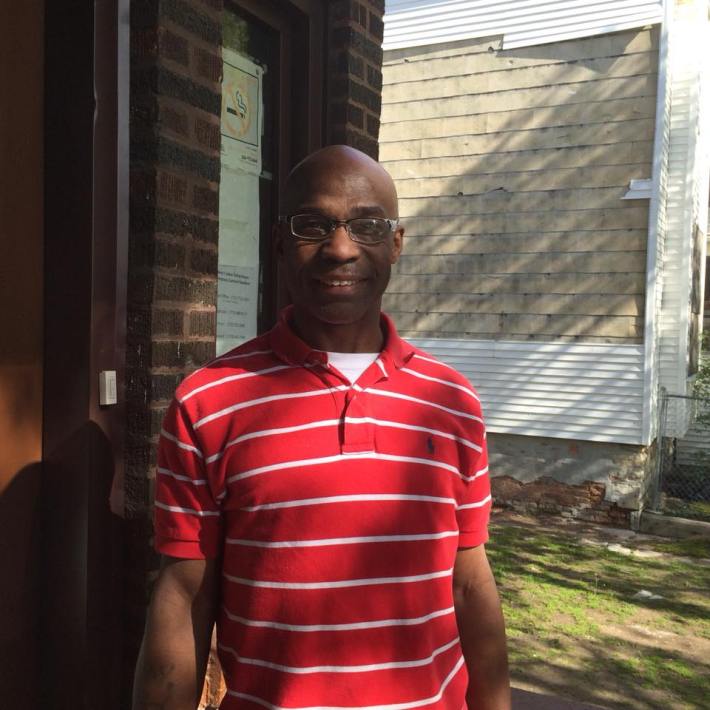

When aldermen block sustainable transportation improvements in their wards, it’s not just a source of frustration for city planners and transportation advocates. It can also put the safety of everyday Chicagoans in jeopardy. For example, last year Luster Jackson, 58, was doored and fatally struck on a bike on Stony Island in the area where Hairston and Harris refused to let CDOT install protected lanes.

But the opposite is also true. With less unreasonable interference from aldermen, CDOT and other city agencies will have more freedom to make positive safety improvements. That’s why Lightfoot’s move to eliminate aldermanic prerogative and prevent aldermen from unfairly blocking proposals in their wards could have a major positive effect for walking, biking, and transit.