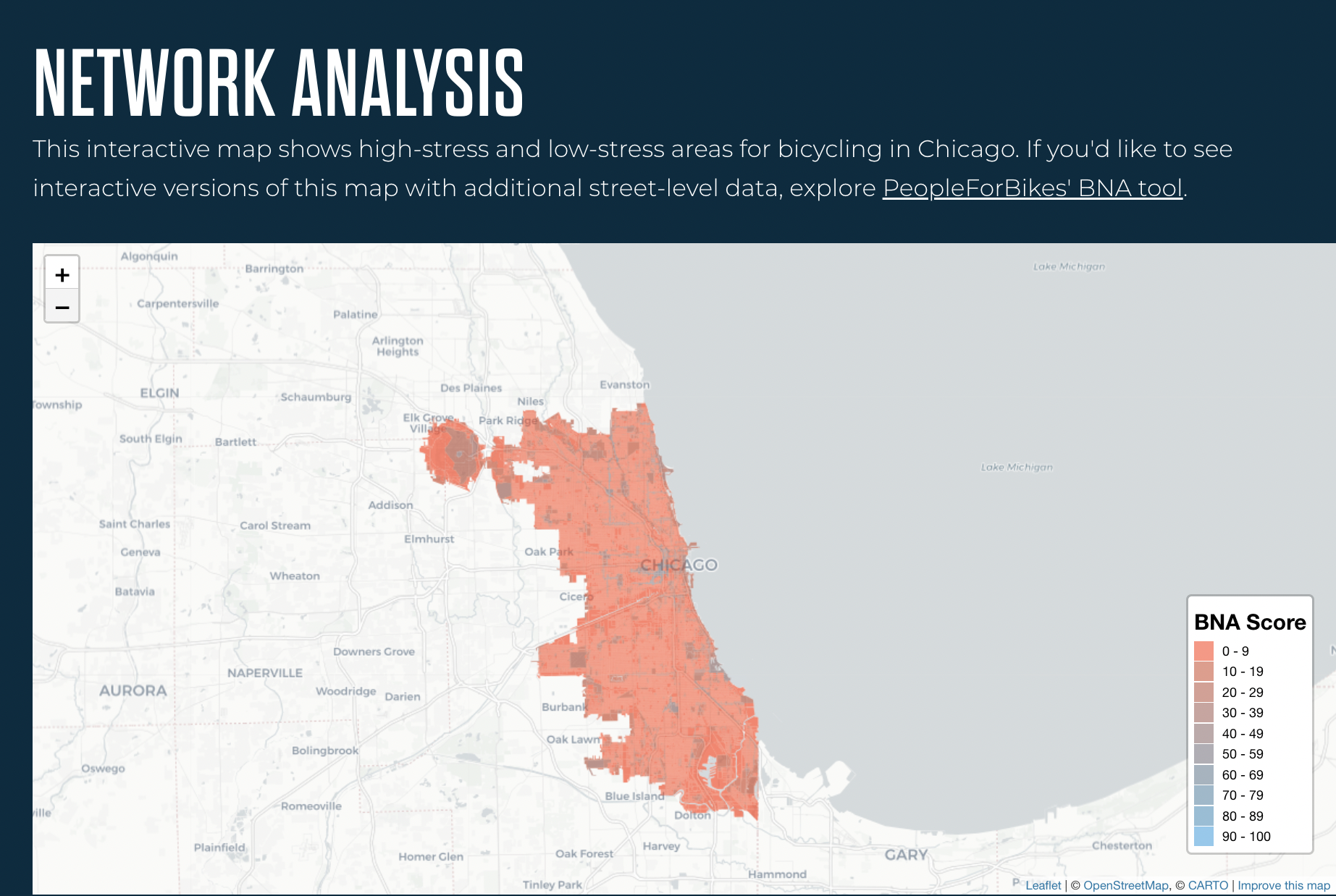

Each year, Colorado-based nonprofit People For Bikes issues a bike-friendliness rating for over 700 cities worldwide. And each year, Chicago can be found near the bottom of the list, ranking below car-centric, bicycle-sparse metropolises like Houston and Los Angeles. 2022 was no exception; the Windy City scored an embarrassing 16 out of 100 possible points for the second year in a row. The lousy rating is due to two factors: Chicago’s high default speed limit and absence of a connected bicycle network of protected lanes.

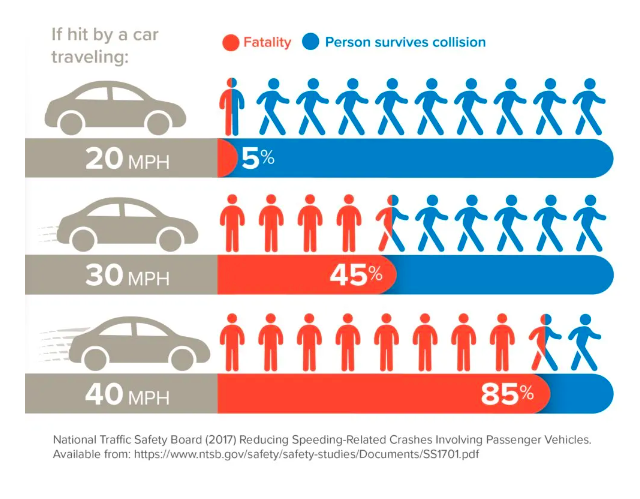

Let’s look at speed limits first. In PFB’s guide to how cities can improve bike conditions and boost their rating, reducing residential speed limits to 25 mph or less tops the list. Traffic speed determines the risk of a fatality in collisions between drivers and people on bikes or on foot. Federal studies found that while pedestrians and cyclists struck by drivers traveling 40 mph have an 85 percent chance of dying, those struck at 30 mph have a 55 percent chance of surviving. However, the chance of survival increases to 90 percent if the driver is traveling at 25 mph. PFB City Ratings program director Rebecca Davies said lowering Chicago's default speed limit from 30 to 25 mph alone would boost our city’s rating from 16 to 42, putting it in the top 15 of large U.S. cities.

Unfortunately, it looks like codifying policies for safe traffic speeds is an uphill battle in our town. Ironically the PFB scorecard was released on the same day a razor-thin majority of alders on Chicago's Committee on Finance voted to pass Ald. Anthony Beale’s (9th) proposed ordinance to allow drivers to speed by as much as 9 mph with impunity to speed cameras. The can has been kicked down the road for now, but should Beale’s ordinance pass, it would condone vehicle speeds of up to 39 mph on most streets, making what is a less-than-safe residential speed limit exponentially deadlier.

Regarding PFB’s safe speed metric, Davies wrote, “given the relationship between speed and risk of injury or death, there is no justification for cities to allow cars to travel faster than 25 mph in neighborhoods.”

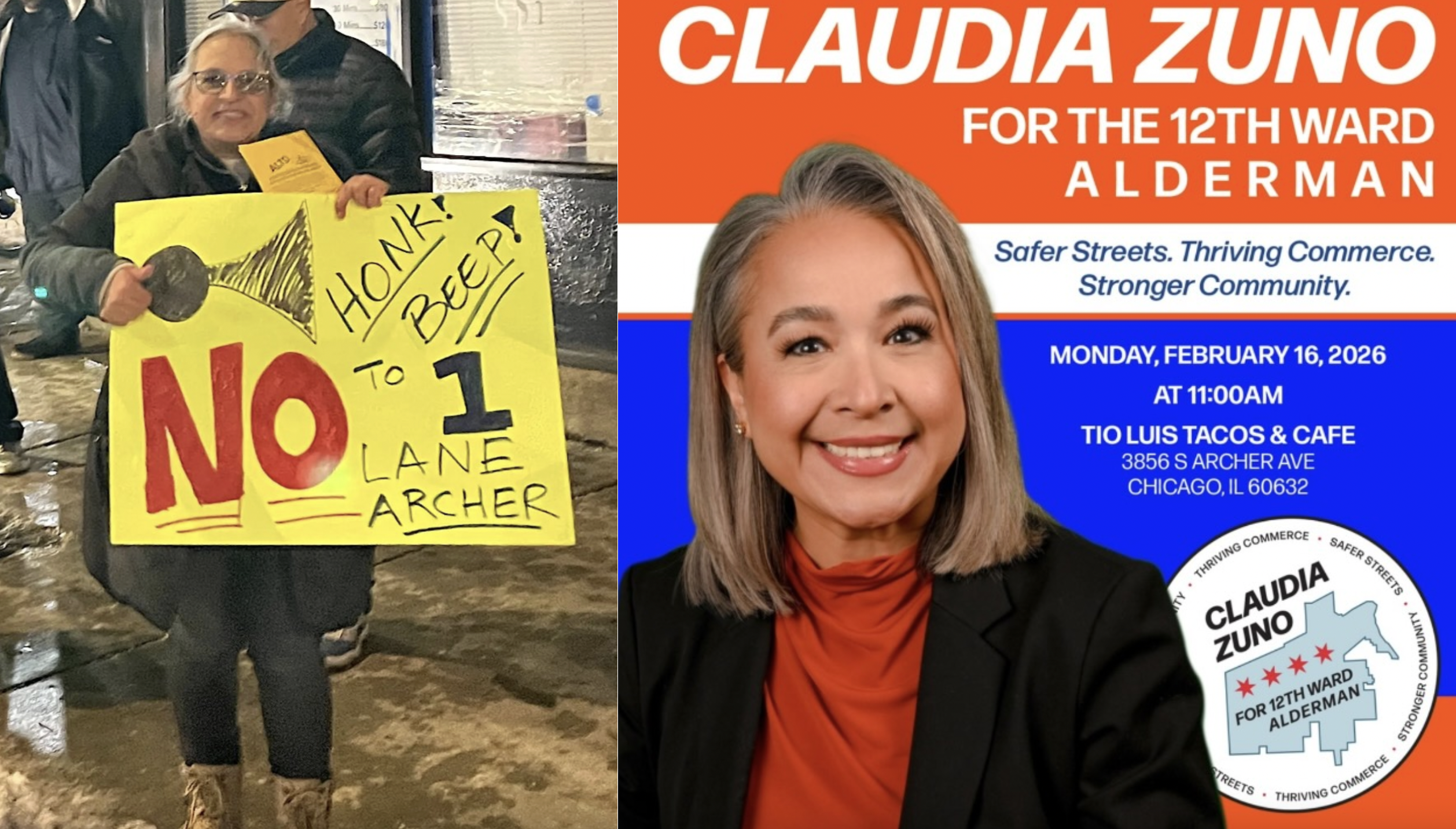

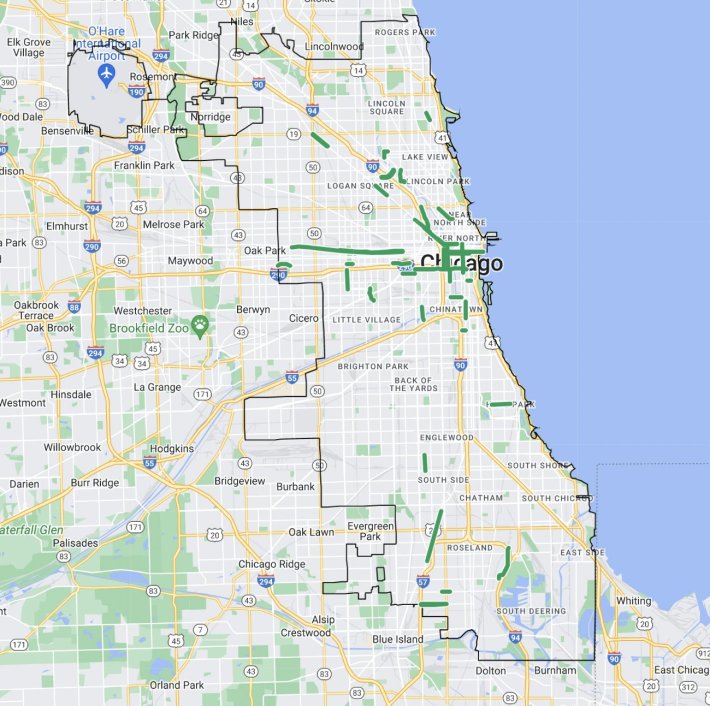

The second factor dragging down Chicago’s bike friendliness score is the city’s piecemeal of protected bike lanes that abruptly start and stop, failing to connect riders to school, jobs, recreation, services, and major transit hubs. Kyle Whitehead, a spokesperson for Active Transportation Alliance, said the PFB score shows just how far Chicago has to go in making bicycling safe and viable for all levels of riders. “For too long, Chicago has taken a patchwork approach to building bike lanes, using paint or plastic to temporarily mark lanes before weather or car and truck traffic limits their usefulness. People riding may feel safe and comfortable for a few blocks of their trip, but they’re inevitably dumped on to a dangerous street alongside high-speed car and truck traffic.”

Shortly after the PFB ratings were released, CDOT announced that all flimsy plastic bollards, which provide no real barrier between cars and bikes on “protected” lanes, will be replaced by concrete curbs or parking-protected lanes by the end of 2023. This is a huge step forward for public safety on existing bike lanes. However, Davies noted that the protections on many of Chicago’s bike lanes, where they do exist, end before intersections where crashes are more likely to occur. These gaps make “low-stress” point-A-to-point-B trips by the PFB standards rare, even along routes where the city has made some investment in bicycle infrastructure. As the city upgrades existing protected bike lanes, it’s worth looking at how extending protections can improve safety where bicyclists are most vulnerable.

The natural inclination when sifting through the PFB City Ratings is to pit cities against each other, sometimes with head-scratching results. I mean, is Las Vegas truly better for biking than Chicago? Whitehead wrote that it’s best not to get hung up on the numbers but focus instead on the key issues in the evaluation. I tend to agree, but there is a peculiarity to Chicago’s score that’s worth noting. (Plus, this is a ranking system so comparing cities is kind of the point.)

The PFB City Rating is calculated with two numbers: a Network Score, which is heavily determined by the factors discussed above and weighted at 80 percent; and a Community Score, weighted at 20 percent and drawn from survey data of resident opinions on biking convenience and safety in their city. Among large U.S. cities, Chicago ranked dead last on the Network Score, getting a measly 5 points out of 100. However, it scored extraordinarily high on the Community Scale, scoring 62 out of 100: Fifth best of large US cities, right after Portland, Oregon. It’s the largest discrepancy between the objective and subjective data of any city—worldwide, of any size—PFB rated.

Davies rightly pointed out that bias plays a big factor in who responds to surveys. Whitehead said the gap in the two scores reflects Chicago’s “strong and growing community of experienced bicyclists”—those most likely to complete the survey. I would contend this strong and growing enthusiasm for biking in the face of inadequate infrastructure and policies that favor moving cars quickly over public safety should be viewed as a mandate to city officials. Chicagoans deserve sufficient infrastructure for biking and safe streets for all users. We can do better.