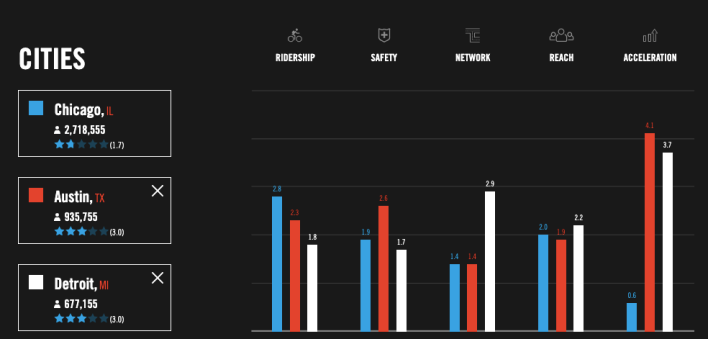

Each year, PeopleForBikes, a Colorado-based bicycle advocacy nonprofit, issues "The Best Cities for Bikes" scorecards for over 600 cities across the U.S. with a bicycle-friendliness rating based on five criteria: safety, ridership, network (how well the bike network connects people to destinations), reach (how well the network serves everyone equally), and acceleration (the city’s commitment to growing ridership). The PFB scale uses European cities like Amsterdam as the gold standard to which American municipalities can aspire.

It's no surprise then that few U.S. cities even broke 3 on a scale of 0 to 5—the two highest ranked in 2020, San Luis Obispo, California, and Madison, Wisconsin, came in at 3.5. Chicago’s score is not only somewhat low—well below Manhattan, Austin, and Detroit—but dropped in 2020 to 1.7, down from 2.0 in the two prior years. So I reached out to PFB to ask the reason for the demotion.

Kyle Wagenschutz, vice president of local innovation at PFB, said the rating drop wasn’t due to a bikability decline in Chicago over the last year, but a data correction; PFB had assumed the default residential speed limit in Illinois was 25 mph, as is the case in much of the U.S. It’s actually 30 mph. “You’ll see the score drop in cities across Illinois,” he said. “Illinois and a handful of other states made a data correction, which in turn changes the stress level of cycling in those cities.”

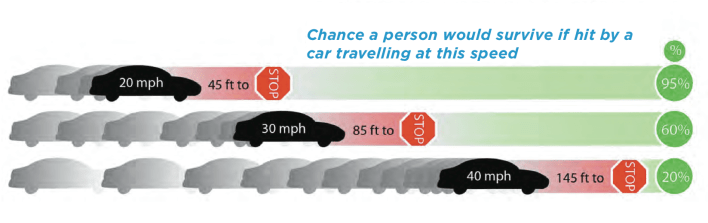

The speed limit correction dealt a nearly one-point blow to Chicago’s network and reach metrics. “The network score is an evaluation of connectivity in a community,” Wagenschutz explained. “We look at how well does a safe, comfortable bicycle network connect you to the destinations you want to travel to. We have thirty destination types: doctor's offices, trailheads, schools, parks, pharmacies, grocery stores, etc. We only use those corridors, trails or roadways that are considered to be low-stress for a relatively inexperienced bike rider. Standard national guidance is that 30 mph is too high a speed for roads to be shared with people riding bikes, so all of Chicago’s residential streets show up as high stress.”

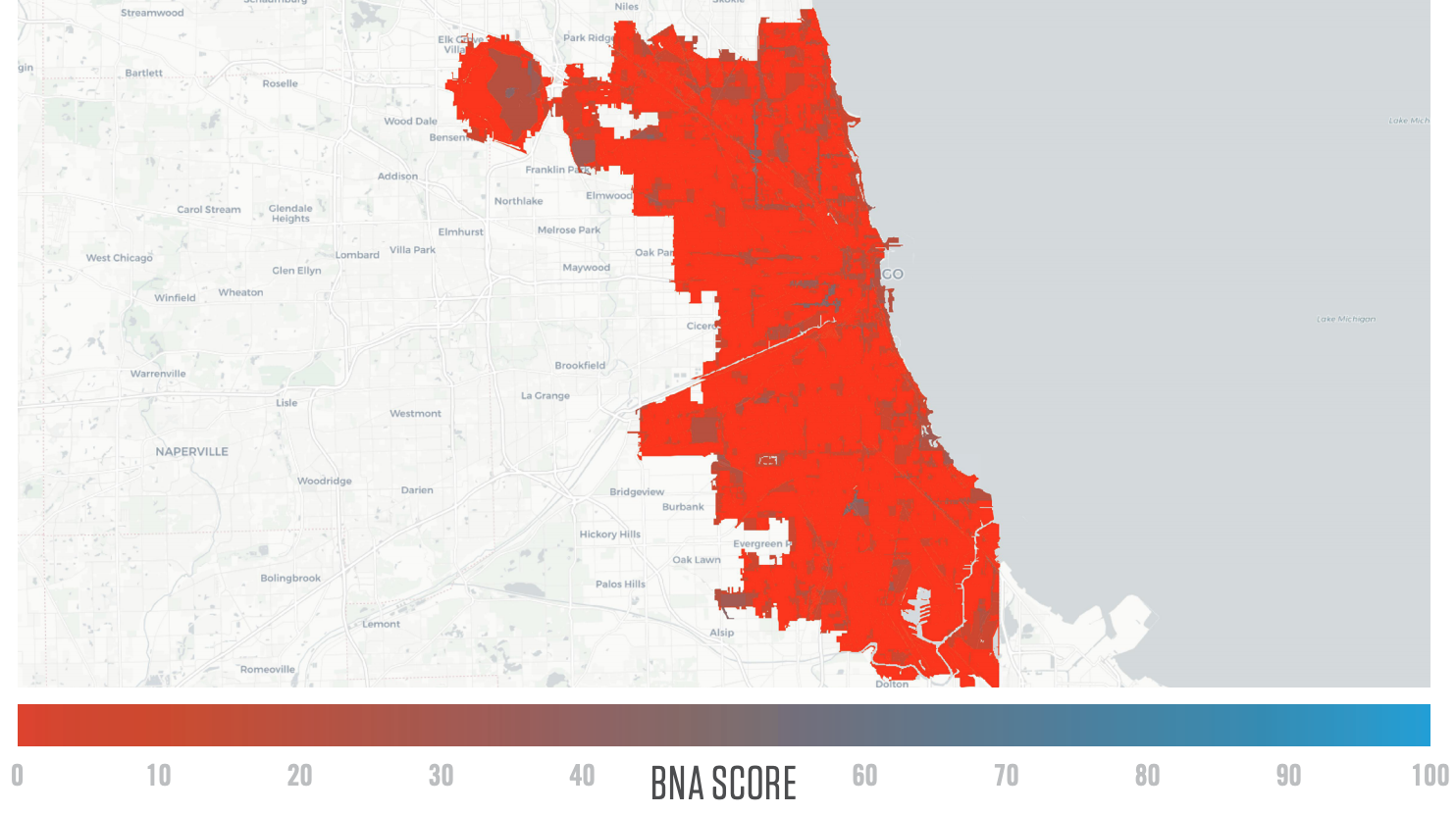

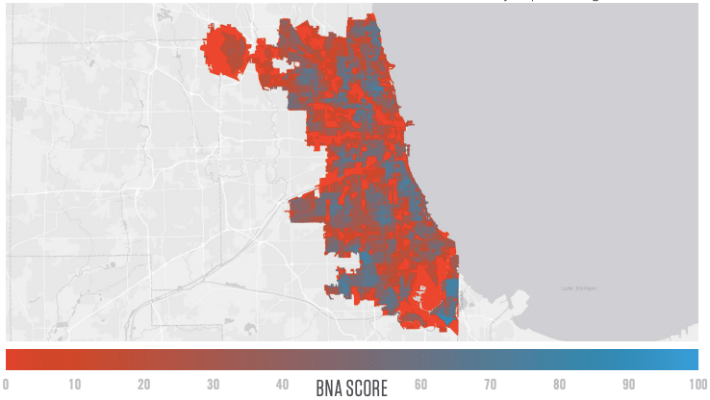

Once PFB corrected Chicago’s residential speed limit, all side streets were effectively knocked off the network. Each scorecard includes a heat map of the bicycle network and, placing the 2019 and 2020 maps side-by-side, the impact of a higher residential speed limit is stunning.

Chicago’s reach score, because it’s closely related to network, took a dive for the same reason. “Reach is a reflection of how the bicycle network serves neighborhoods throughout the city,” Wagenschutz said. “Reach looks at how that connectivity works for pre-identified populations within the city.” The loss of residential streets as identified parts of the network also registered as a drop in how well Black and Latino communities on the South and West sides are served by the roads, trails and bike lanes identified as part of a safe, comfortable network.

“This is further evidence of how far we have to go in building a network of streets where all Chicagoans feel safe and comfortable biking," said Kyle Whitehead, spokesperson for the Active Transportation Alliance. "It’s difficult and often dangerous to ride a bike on most Chicago streets. The challenge is greater on the South and West Sides because bike facilities aren’t equitably distributed. These areas need more infrastructure because destinations are further apart and streets are wider with faster car and truck traffic. In recent years we’ve seen fewer protected bike lanes and more painted lanes. This lower quality infrastructure provides some benefit for people already riding on these streets but doesn’t really move the needle on safety, or get more people to ride.”

At the outset of ATA's last town hall meeting, the group's campaign manager W. Robert Schultz III said the organization has a long-term goal of universally reducing residential speed limits in Chicago to increase both bicycle and pedestrian safety. Schultz said a reduced speed limit is critical to Chicago’s Vision Zero commitment to eliminate serious and fatal crashes.

Chicago Department of Transportation spokesperson Michael Claffey argued that the lower PFB rating doesn’t reflect substantial bicycle infrastructure improvements made over the last year. “We strongly disagree with the change in ratings because they don’t seem based on up-to-date information on our bikeway progress in 2020. And we have big plans to build on this progress in 2021, thanks to a significant boost in funding from the city’s new five-year Capital Plan.”

Claffey pointed to the 30 miles of new bike lanes installed this year, over half of which were added to the South Side, in concert with the expansion of Divvy and the introduction of electric-assist bikes to the Divvy fleet. Claffey also cited the new Lincoln Village bike/ped bridge that traverses the North Shore Channel and recently installed plastic curb-protected bike lanes on Milwaukee Avenue in Logan Square. “The project is part of CDOT’s Vision Zero traffic safety program; this also includes pedestrian safety infrastructure and transit access improvements, all designed in coordination with residents, businesses and the Logan Square Chamber of Commerce,” he wrote.

As for lowering residential speed limits, Claffey said CDOT is in favor of this, “where possible, especially when there is community support,” pointing to CDOT’s recent recommendation to lower the speed limit on Damen Avenue between Diversey and Belmont avenues in conjunction with new dashed bike lanes. Barista Liza Whitacre, 20, was run over by a truck driver and killed on that stretch in 2009.

The improvements Claffey sited are supporting data for another metric for which Chicago has been dinged—unfairly—on the PFB scale: acceleration. Wagenschutz said PFB relies on cities to self-report their improvement plans, and CDOT hasn’t submitted data to date. Lack of measurable data resulted in low acceleration marks, hurting the overall score. It’s the reason why cities like the above examples of Austin and Detroit rank above Chicago: Other metrics like reach, network or safety might be on par, but these cities gained points for reporting their progress toward improving biking.

Wagenschutz sees this as a flaw in the system and said PFB is revamping the scorecard next year so cities that don’t submit acceleration data aren’t penalized. “It makes it hard to make apples to apples comparisons and it’s hard to gauge year-to-year comparisons between cities. And even year-to-year within the same city if they report one year but not the next."

“I assume cities like Chicago are inundated with requests like this,” he added. “The act of somebody taking the time and energy to report to us and probably 50 other organizations asking for the same data is burdensome.”

Wagenschutz named a few other ways to give Chicago’s Best Cities for Biking rating a bump in the future. “The city has been building protected bike lanes for a number of years, but accelerating and expanding that network, particularly along arterial roadways is important to improve its score,” he said. “The other thing I notice: those protected bicycle lanes, being able to connect in a more direct way to the city’s transit access lines could also have a lot of benefits to bicycling generally speaking.” The $37 million in the capital plan for bikeway improvements over the next five years is a promising commitment to improving the comfort and reach of Chicago’s bike network. Reducing residential speed limits is clearly a high-impact, relatively low-cost change that belongs in the plan as well.