At yesterday's ribbon-cutting for the nifty Augusta Boulevard protected bike lanes, during the press conference I asked Chicago Department of Transportation Commissioner Gia Biagi, who's stepping down tomorrow, how aldermanic prerogative affected her efforts to install bikeways across the city. Aldermanic prerogative, aka aldermanic privilege, is the longtime Chicago tradition of alderpersons having the de-facto right to veto infrastructure projects in their wards.

Immediately after former Mayor Lori Lightfoot took office in May 2019, she signed an executive order that supposedly ended the practice. However, by November of that year, CDOT officials basically acknowledged that alders still had the power to kill proposed safety initiatives in their districts. Aldermanic privilege is a big reason why South and West side communities generally have fewer, and less connected bikeways than their North Side counterparts, and why some neighborhoods where anti-cycling sentiments are common have few or no bike lanes.

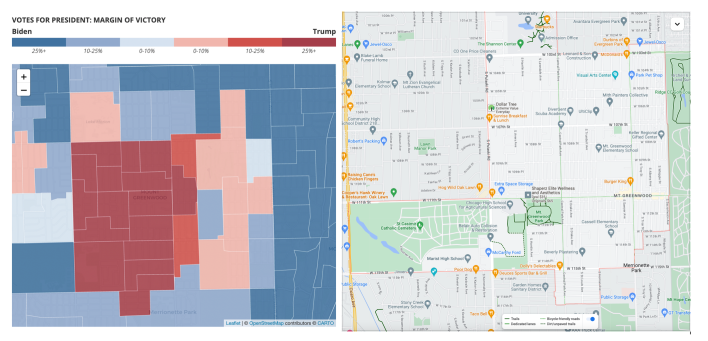

John Greenfield: What comment do you have about the issue of aldermanic prerogative in Chicago and getting projects like [the Augusta protected lanes] built? We all know that Alderman [Daniel] La Spata [1st, the local representative] is very bike-friendly. A couple weeks ago you were at a ribbon cutting for a streetscape project [with no bike lanes] on 111th Street [in Mount Greenwood] in the 19th Ward, which is a less bike-friendly neighborhood – it got a lot of votes for Trump in the last election.

So bike projects don't tend to get built in parts of town where the alder[person] is not supportive or the residents aren't supportive. But in progressive areas like this you're much more likely to get a nice bike project like this. How did that affect your work as commissioner?

Gia Biagi: I'll also let the alderman also talk about aldermanic prerogative, perhaps from his perspective. From my perspective, what's important is that we get these projects into play, no matter where they are, so we have great examples. But that we also spending time with aldermen, more than one alderman at the same time, right? The boundaries are artificial in a way.

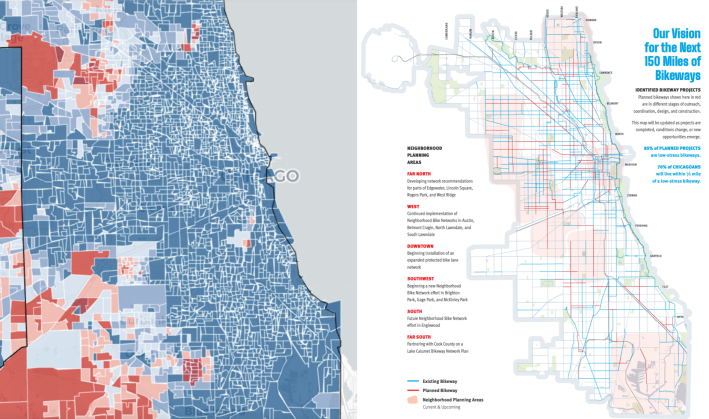

And so what we've begun to do is sit down with groups, together, who may have different opinions about what bike infrastructure means to them, and they're all reflecting different constituent interests. But I think developing a cohort of aldermen and a cohort of wards is gonna help us get there. And I think also that was why it was so important that we laid out, 'Here's what what we think are the next 150 miles [of bikeways, in the 2023 Chicago Bicycling Strategy plan],' we're putting that on the table.' I can't remember a time when the city has said, 'We're just going to draw it on the map, and everybody talk about it, and this is where we'd like to go.'

We're also trying to be trying to be really transparent, so it's not a surprise, and it's not block-by-block, but here is the system in which this exists. There are a lot of aldermen who are very interested in this, but we have to move at the pace of their constituents. And that's why in some cases it might take a little longer. In some cases we're going to hold hands across a ward boundary, but we're going to get it done.

Ald. Daniel La Spata: I hear the critique. If you ride down Milwaukee Avenue, even over the course of two miles, you can go from a dashed line, to a striped line, to no line, to a "sharrow" [bike-and-chevron symbol], to a protected bike lane. Sometimes to see in the past how that lined up with ward maps was challenging. Sometimes the redistricting of our [aldermanic] maps also complicates that. We need collaboration, we need cooperation. But I think over the course of the next few years we also need to consider or perhaps challenge how aldermanic prerogative might hurt [the goal of creating a citywide, connected bike network.]

Did you appreciate this post? Please consider making a tax-deductible donation.