Bike lane advocacy in Chicago tends to focus on whether a bike lane is “protected” or not. But too often on this city’s streets, a well-protected bike lane disappears before the intersection. Bike riders are forced to share space with right-turning drivers in “mixing zones” at intersections that neither look good on paper nor work well in practice.

Most crashes between people biking and and driving occur at intersections, so protecting cyclists as they ride through the junction is crucial. The solution is a protected intersection. These were invented by the Dutch, but have spread around the world and are even beginning to pop up here in the U.S.

The protected intersection is a little tricky to wrap your head around, but in practice biking through one is very intuitive. As one cyclists said, "It just works." Here's a "view from the handlebars" video from Mark Wagenbuur of Bicycle Dutch turning left and right through a Dutch protected intersection that will give you a better sense of what it's like.

A protected intersection follows three principles:

- Even though they must eventually cross paths, drivers and bike riders should be kept separate as much as possible

- When they do cross, they should cross at right angles for better sight lines

- Everything is safer when it happens at low speed

Let’s take a look at a typical intersection for a Chicago protected bike lane – and then sketch out how to make it into a protected intersection.

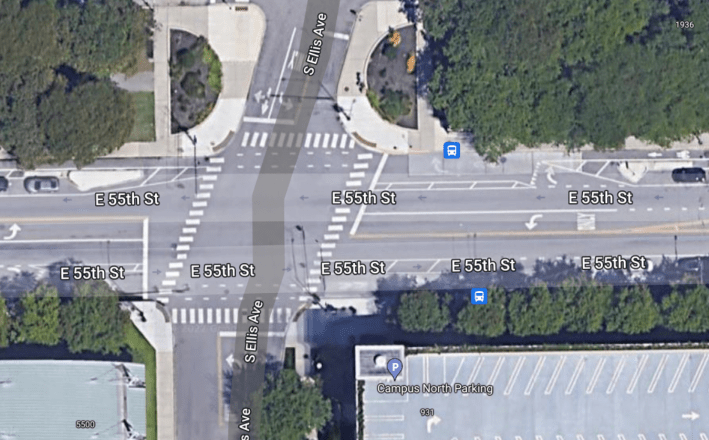

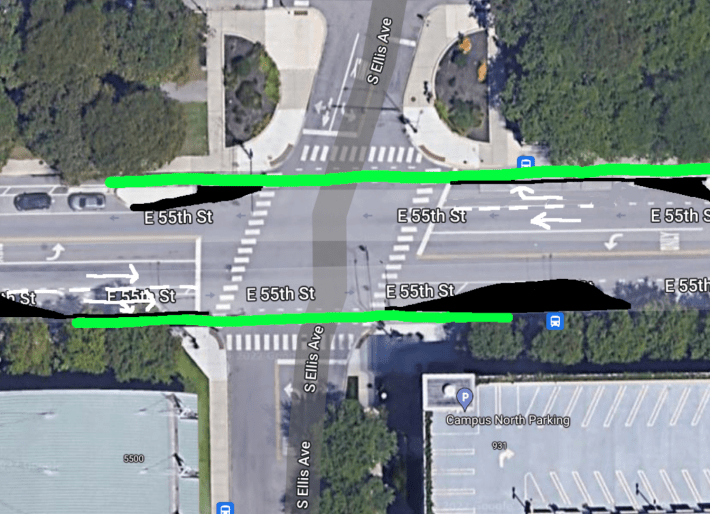

Here’s an intersection I ride through all the time, at 55th Street and Ellis Avenue in Hyde Park, heading west. (There is also a bus stop here, but intersections on this street without a bus stop have a similar design so we’ll cover bus stop treatments in a future article.)

The first thing to notice is that the physical protection ends 107 feet before the stop line, and the total distance that the bike lane is unprotected is 218 feet. That’s about one-third the length of a typical 660-foot Chicago block! So a person riding in this “protected bike lane” is actually exposed about one-third of the time.

The second thing is that right-turning drivers have to merge with the bike lane in a very dangerous way. The merging motorist has just cleared a line of parked cars, so neither cyclist nor driver can see each other until right at the merge point. And at the angle the driver enters the shared lane, the cyclist is in their blind spot. While the law here is the driver must yield to the bike bike rider, the reality is the cyclist must yield or risk injury.

And finally, with the shallow angle of the merge, the driver could easily enter this lane at 30 or 35 mph, a speed which makes a collision both more likely and more dangerous.

Ok, let’s fix this! The first step is to follow Principle 1 and keep the drivers and bike riders separate as much as possible, by adding curbs, black in the image below.

The easiest thing to do is just keep the bike lane protected by a curb until the crosswalk and not have it merge with the right turn lane in a mixing zone. I measured, and there is room for a 11-foot-wide through lane, a 10-foot turn lane, a 1-foot curb, and a 5-foot bike lane without moving any existing curbs. Doing this would immediately reduce the length of exposure from 218 feet to 74 feet and also prevent drivers from illegally parking in the bike lane.

All thru COVID we've been experimenting with street safety techniques in plastic. Glad to see crews replacing successes with concrete. 5th/Howard pic.twitter.com/nJO7BpO1Z3

— Jeffrey Tumlin 🏳️🌈 (@jeffreytumlin) March 5, 2022

In San Francisco, while there is concrete protection leading up to the intersection, the city opted for rubber speed bumps and flexible plastic posts for the corner refuge island. While that's not as good as concrete, it forces most traffic to take the tight turn slowly, while allowing large trucks (and fire trucks) to drive over the island at a slow speed if necessary. In places where a full corner refuge island is not possible under current law, this is a good way of getting most of the benefits without abandoning the general format, as long as it comes with a commitment to replacing these elements when they are inevitably damaged. In Europe it is common to use low-curb concrete islands in these cases. Drivers of large vehicles can still drive over them if necessary, but they're less likely to get destroyed by a snow plow operator.

In general, CDOT and and the Illinois Department of Transportation need to stop reinventing the wheel and just copy protected bikeway designs that work well elsewhere. Where creativity is warranted and welcome, though, is in finding ways we can quickly deploy known solutions like protected intersections without having to change existing laws or buy a whole fleet of smaller fire trucks. In these cases, creative solutions like we see in Salt Lake City and San Francisco are what we should be looking for from our transportation engineers.