Streetsblog Chicago has fact-checked anti-bikeway articles from the local "Not In My Back Yard" neighborhood newspaper chain Inside Publications many, many times. Their publisher / editor Ronald Roenigk should make a donation to us for all the free publicity he's gotten.

But, sorry, if widely circulated print publications are going to put out nonsense about safe streets projects, and other local walk/bike/transit advocacy organizations, it's my responsibility as SBC editor to debunk it. So let's get to work.

On Monday, I heard about Inside Publications' latest "report" about bikeways on the Near North Side and in Edgewater titled, "Bike lanes get privilege over buses, emergency vehicles, disabled." Read it at your own risk.

I wasn't the only person who suspected the byline of this new piece might be fake. After all, Roenigk has a well-documented history of writing articles under pseudonyms.

But as it turns out, the person credited as the author of the new article seems to be an actual, non-Roenigk human being. It turns out Peter Von Buol is a Columbia College adjunct journalism professor. But it's shocking that he has taught other people to write news articles, because the lack of research and tortured prose in his new Inside Publications piece is truly appalling.

Let's give Von Buol the benefit of the doubt that Roenigk wrote the obnoxious headline. Read my deconstruction of the editor's longtime slur of protected bike lanes as "privileged bike lanes" here.

But Von Buol's very long first sentence is a quite a piece of work. "As the City of Chicago continues to implement its bicycle-focused Complete Streets program, which adds road obstacles with the specific purpose of slowing down all motorized vehicle traffic, including Chicago Transit Authority and Chicago Public Schools buses, police cars, firetrucks, ambulances, and United States Postal Service vehicles, public transit passengers have been experiencing dramatic changes at some bus stops."

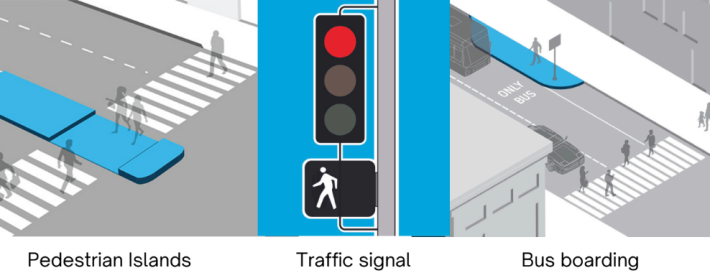

Where to start? Chicago's Complete Streets initiative isn't "bicycle-focused." Rather, as its website states, "Complete Streets benefit all modes of transportation – walking, biking, rolling, public transit, and driving – by making our streets safer and more accessible for everyone." Some of our city's Complete Streets projects don't really involve cycling facilities at all, such as recent improvements to Ashland and Western avenues in the 40th Ward. These included sidewalk bumpouts, pedestrian islands, bus boarding islands, and/or bus-only lanes – benefitting people on foot and transit – but no bike infrastructure to speak of.

Yes, Complete Streets projects are often designed to calm traffic by discouraging speeding. That's important, because people struck by drivers doing 30 mph, Chicago's default speed limit, usually survive, whereas those hit at 40 almost always die. That was a major factor in drivers killing 38 pedestrians and bike riders in Chicago last year. In addition, 69 people in motor vehicles died in crashes here in 2024.

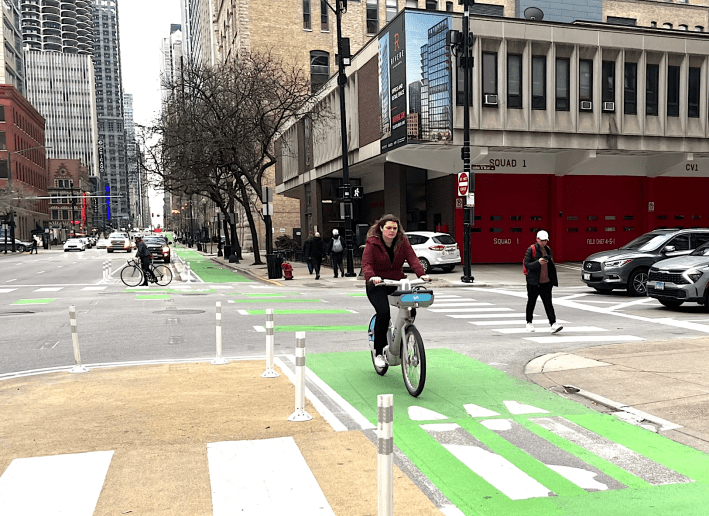

Safer street designs, including layouts with protected bike lanes, generally don't make it any more difficult to drive the speed limit. And, contrary to popular belief, there's no evidence that these street remixes delay first responders. In multiple news reports about streets like Chicago's Augusta Boulevard and Dearborn Street, a Chicago Fire Department spokesperson has reported that, despite worried neighbors, new PBLs don't appear to be delaying fire engines.

If you won't take CFD's word on it that emergency vehicles can quickly get through PBL streets during busy times, watch the video below of Clark Street next to Graceland Cemetery from the 1:15 mark. The relative ease with which the ambulance driver travels the crowded roadway isn't surprising, because the Chicago Department of Transportation often collaborates with first responders on street redesigns.

Like Roenigk, Von Buol claims "privileged bike lanes" are making things harder for other road users. For example, he writes that PBLs have "made it more difficult to exit from a bus directly to the sidewalk." True, bus boarding islands and sidewalk extensions on streets with protected or raised bike lanes mean that CTA customers board and disembark a little farther from the the sidewalk proper. And they also have to cross the bikeway to access the bus.

But these layouts also offer benefits for passengers and people on foot. Since the boarding area aligns directly with the travel lane, the bus driver doesn't have spend time pulling to and from the regular curb, which shortens transit trips.

In this video, a bus driver is able to stop alongside a sidewalk extension and raised bike lane to pick up a passenger, and then quickly depart, without having to waste time traveling to and from the old curb.

And while CTA customers and pedestrians have to check for people on 40-pound bikes and e-scooters before crossing the green-painted bikeway, that's a lot safer than avoiding faster-moving, 4,000-pound vehicles on "car" lanes. Moreover, the total street crossing width is dramatically shortened, as you can see in the images below.

The main complaint in Von Buol's tirade is about the state of the bus stop for the Newberry Library, 60 W. Walton St. on the Near North Side. The only human being the journalism teacher quotes in the entire article is West Ridge resident Jean SmilingCoyote, complaints about the Newberry and Edgewater bike lanes.

SmilingCoyote too seems to be a real person, rather than a construct. A Google Search uncovered a letter she wrote to the Chicago Reader 20 years ago, titled, "Home Is Where the Car Is." "We Americans... have the right to travel–in our cars if we can and wish," SmilingCoyote argued in the letter. Lest that passage makes you think she's a total motorhead, Von Buol mentions that she regularly rides the #22 Clark bus to events at the library.

Want to help ensure Streetsblog Chicago can keep publishing articles like this for another year? Please consider making a tax-deductible gift here. Thanks!

SmilingCoyote's grievance that the #22 and #70 Division buses aren't currently stopping next to the sidewalk in front of the library, as they were before Walton got a partial PBL, with bollards near Clark, is not totally unwarranted. She says customers are forced to enter the street to board the bus.

But what Von Buol doesn't mention is there's currently no official bus stop at the library for the Clark and Division buses at all. That's not because of the protected lane on Walton, but because of road construction for a new concrete bus pad. (There is a space east of the main Newberry entrance where bus drivers can presently wait between shifts, and let passengers sit down in the vehicle if these choose.)

A sign on the old Walton bus stop sign explains that the Newberry stop is currently out of service, so passengers should go west, around the corner, and north on Clark a short distance to the bus shelter at Oak Street.

Von Buol didn't mention that sign. On Monday, I contacted the CTA for more information about what's going on at the Newberry, and a spokesperson implied they'd get back to me on Tuesday after touching base with the Chicago Department of Transportation. If that happens, I'll update this article.

Update 4/9/25, 4:30 PM: Streetsblog just got a full response from a CTA spokesperson. "CDOT is installing a concrete bus pad in front of the Newberry Library entrance," they emailed. "When that construction is complete, CTA will be able to move the bus stop to its final accessible location (a bit east of where the bus stop pole is currently), which will correct the issue of the bus stop pole being adjacent to the bike lane flexi-posts."

"While the bus pad is being built, the stop is signed as temporarily out of service, and customers are expected to use the next available stop at Clark/Oak northbound farside [at the northeast corner of the intersection]," the spokesperson added. "This is normal construction coordination, and we expect to wrap up soon."

There's no indication Von Buol even asked the CTA for an update. It also appears he didn't actually visit the library site, since both of the photos in his article were taken by SmilingCoyote. Altogether, this rather lazy approach is an effective lesson for his journalism students on how not to write a news article.

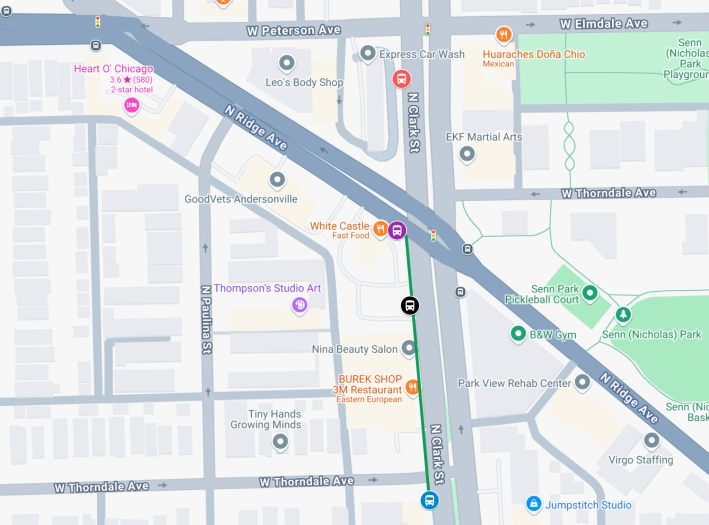

SmilingCoyote also complains that, up in Edgewater, a southbound #22 Clark bus stop on the west side of Clark, just south of a White Castle at Ridge Avenue, was removed to accommodate protected bike lanes on Clark. She claims that passengers heading east on #84 Peterson Avenue buses, which turn southeast on Ridge just before Clark, are now required to head north from the slider joint and cross busy, four-lane Ridge. Then, she says, you have to catch a southbound #22 from a stop on Clark just south of Elmdale/Peterson. Presumably, this is her bus commute from her home in West Ridge to the Newberry Library.

"They have forced passengers to use the Elmdale/Peterson stop instead," she insists. "It's only that blasted bike lane hardscaping that has messed it up." But it's not actually true that the street redesign requires people to cross Ridge in order to make this transfer.

In reality, if you're switching from an eastbound #84 to a southbound #22, for most people it doesn't make sense to head north across Ridge to the Elmdale/Peterson stop (red bus icon in the above map). There's another southbound #22 stop on Clark just south of Thorndale Avenue (blue icon). That's in your direction of travel, with no major street crossing. Sure, it's not as convenient as it was to simply go around the corner from the Peterson stop on the north side of White Castle (purple icon) to the old stop on the east side of the burger place (black icon). And people who need or want to minimize their travel distance might choose to head north to Elmdale/Peterson instead. But the trip from the #84 stop to the Thorndale stop is still only 520', less than one standard Chicago block.

Here's one more very annoying thing about the Inside Publications article. Von Buol writes that the Active Transportation Alliance, Chicagoland's leading walk/bike/transit advocacy group, provided input for the region's Complete Streets planning. "While ATA bills itself as a membership-based transportation advocacy organization, it is a powerful special interests organization funded primarily by government grants," he sniffs.

That's a grossly misleading statement. ATA doesn't just claim to be a member-driven organization. It actually gets a significant amount of its funding from memberships, donations, and its annual Bike the Drive fundraiser, happening this year on Sunday, August 31.

And what exactly was Von Buol's evidence that ATA is "funded primarily by government grants"? I emailed the question to Roenigk, his editor. "We based it on their IRS 990 [nonprofit information report] filings, and asked them directly in an email," he replied.

The thing is, Van Buol's statement doesn't jibe with reality. In just about all of ATA's 990s from the last five years, revenue from "Contributions" was much higher than that from "Program Services." (There was exactly one report where the numbers were basically tied.)

And when I asked ATA directly in an email, spokesperson Ted Villaire replied, "In recent years, the majority of our revenue has come from fundraisers and membership dues."

So not only is Van Buol’s statement that ATA is "primarily funded by government grants" patently false. Roenigk's claim that they checked the 990s and asked ATA about this is extremely shady, like much of what his publication sees fit to print.

Read "Bike lanes get privilege over buses, emergency vehicles, disabled," if you feel you must.

Did you appreciate this post? Streetsblog Chicago is currently fundraising to help cover our 2025-26 budget. If you appreciate our reporting and advocacy on local sustainable transportation issues, please consider making a tax-deductible donation here. Thank you!