Update 10/16/24, 12:15 PM: Here's an interesting tidbit about this issue. On September 16, the 43rd Ward told Streetsblog, "Because there is adequate width on the street, bike lanes will border the single lane of [westbound motorized] traffic, continuing the intended use of the Dickens Greenway."

Of course, that's not what happened. As you can see from the photo at the top of this post, there is no westbound bike lane to the right of the westbound mixed-traffic lane. Instead, there's a so-called "shared lane" requiring bike riders and scooteristas to travel directly behind and in front of drivers, which can be dangerous. It's a relatively narrow lane, so there's no room for sustainable transportation device users to ride next to the curb to allow motorists to pass them on the left.

"The design hasn’t changed," Chicago Department of Transportation spokesperson Erica Schroeder told Streetsblog today. "This is what was coordinated with the alderman based on the ward's feedback and the available widths at the intersections."

Let's not make too big a deal out of the fact that, assuming the CDOT response is accurate, it appears the ward statement was not. People make errors.

But this begs the question, why didn't CDOT get rid of the tan portion of the road, shown above, and shift the westbound mixed-traffic lane a few feet south? It appears that would have made room for curbside, concrete-curb-protected bike lanes in each direction, which would have been much safer.

Schroeder didn't reply to that question, but we'll post another update if we get a response to this suggestion.

Update 10/15/24, 1:15 PM: After publication of this article, the Active Transportation Alliance (a Streetsblog Chicago sponsor) Advocacy Manager Alex Perez provided a statement about the Dickens Greenway plaza issue.

"At ATA we advocate for safe walking and biking routes, so it is unfortunate when safety improvement infrastructure like the Dickens Plaza is removed," Perez said. "The implementation of the Dickens greenway and the plaza has been a great addition for people of all ages and abilities to feel safe and comfortable riding their bikes when traveling to and from the lake."

"The greenway took years of advocacy to get implemented and was removed without any public meeting about the decision," Perez added. "Opening vehicle traffic to travel west on Dickens and Stockton Drive creates the potential for a crash to happen in the future that could have been preventable with the Dickens plaza not being removed."

"We do not want the removal of the Dickens Plaza to be an example and affect future safety improvement projects CDOT is working on in other parts of Chicago," Perez concluded. "We should be working together to add more safety improvement infrastructure across the city to help with slowing down drivers from speeding and preventing crashes."

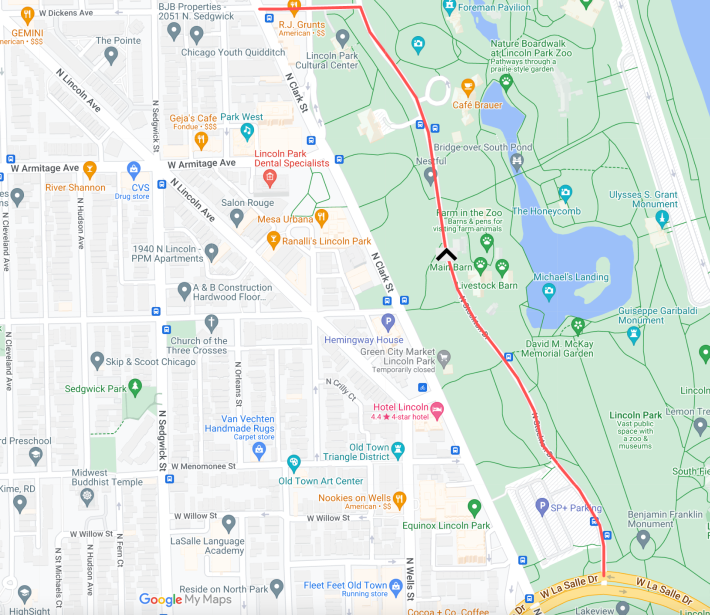

At this point, most Streetsblog Chicago readers are probably very familiar with what happened last week with the Dickens Greenway plaza, located at Dickens Avenue and Lincoln Park West in the Lincoln Park neighborhood. If not, you can read this article to get up to speed.

In a nutshell, it took four and a half years of community meetings and advocacy for residents and sustainable transportation boosters to get the 1.4-mile Dickens Greenway bike-ped-priority side street route installed, opening last January. The project included the plaza, a traffic diverter that discouraged dangerous "cut-through" driving on the greenway and in the Lincoln Park green space. But it took only nine months of behind-the-scenes lobbying by drivers, with zero public meetings, to pressure local Ald. Timmy Knudsen (43rd) and the Chicago Department of Transportation into eliminating the plaza last week.

I've done plenty of commentary on Streetsblog and social media since Friday, when motor vehicles were once again permitted to drive from Stockton Avenue, the main north-south park road, west onto the greenway corridor. So for a different perspective on the issue, let's take a closer look at what other local walk/bike/transit advocates recently had to say about it.

Rony Islam is the cofounder of Chicago, Bike Grid Now!, which is pushing for a citywide network of low-stress, bike-priority routes. Molly Fleck is a sustainable transportation activist and bike mom who lives in the 43rd Ward. They both gave speeches at a protest CBGN! organized last month at the plaza, which drew some 150 bike riders.

Nick Reichert, host of the national podcast Bike Talk recently invited the three of us on his show to discuss this Dickensian saga, before CDOT removed the plaza. Islam and Fleck did a great job of zooming out to discuss how the elimination of this small public space has big implications for Chicago's efforts to reduce crashes, pollution, and congestion by creating a safe, citywide bike and e-scooter grid.

I've also reached out to Islam and Fleck for post-Friday commentary, which I'll add as an update if they have more to say.

Here are some key passages from the Bike Talk interview, edited slightly for clarity and brevity.

Molly Fleck (from the Bike Talk interview): Before it became a greenway route, Dickens was a mostly one-way street for westbound car traffic. It's very wide. It's kind of unusually wide for a one-way street. There's street parking on both sides. And it's one block north of a street called Armitage Avenue that's a more major street that has a bus route and it does have painted bike lanes.

The nice thing about Dickens, though, is that when it became a Greenway, it added a contraflow lane for bike riders. So people on bikes are allowed to go both ways, but drivers are not. And it connects a couple of major parks. So Lincoln Park, the neighborhood, is named after Lincoln Park, the park, which is a massive park along Lake Michigan, on the eastern side of the neighborhood. So the greenway connects Lincoln Park, which, if you ride through that park, will connect you to the famous Lakefront Trail in Chicago, which is our marquee piece of bike infrastructure in the city of Chicago.

Dickens is a great way to provide an east-west route between the Lakefront Trail and Lincoln Park, the park, to the rest of the city. You're able to go west all the way almost to the river, and then once you cross the river you can take The 606 [aka The Bloomingdale Trail], which is a former elevated rail track, which has been converted into a pedestrian- and bikeway.

The Dickens Greenway is mostly just paint on the ground. There are some pedestrian bump-outs. There are a few really good raised crosswalks that have helped by some of the neighborhood schools. It crosses through Oz Park, which is a great local neighborhood park, with a playground and baseball fields, and Lincoln Park High School is right there. So there are a lot of things that it helps to connect. And that's why I think it was chosen as a greenway route.

Towards the eastern end, one of the things that was added on later in the process was a traffic diverter [The Dickens Greenway plaza]. So motorists used to be able to drive all the way east as far as they could, to a road called Stockton Drive, and that's kind of the last road in the park. And this traffic diverter stop drivers from being able to cross all the way to Stockton. Bike riders can still go through. It's still kind of a permeable barrier to bikes, but it's formed a very small, little pedestrian plaza.

And so the plan going forward is that it is no longer going to be a complete diverter for drivers. It still will partially divert car traffic, because previously it was two-ways for drivers there. So now they're going to re-open it to allow westbound motor vehicle traffic, and then there still will be a couple of protected bike lanes to allow the bike riders to continue to go through.

[An aide to Ald. Knudsen's office told us, "Because there is adequate width on the street, bike lanes will border the single lane of traffic, continuing the intended use of the Dickens Greenway." However, the current design only has the "shared" westbound lane, dangerously sandwiching bike and scooter riders between motor vehicles.]

But the frustration is that modifying this traffic diverter threatens to add additional car traffic onto the Dickens Greenway, which is supposed to be a low-stress bike route. And low-stress means low-traffic, generally. So I think that's the frustration, getting rid of that traffic diverter.

And it also just sends a symbolic message that the voices of drivers are more important that the voices of cyclists and pedestrians. And so I think that something that Rony and Chicago, Bike Grid Now! have been advocating for is this protected bike grid, and that there are certain streets that need to be cyclist-priority. We're talking about a very small physical portion of the greenway that's going to be affected. But I think the symbolic message that is much louder is that, even on roads that have been designated for cyclists, the preferences of drivers are sill strongly considered, even over the needs of cyclists.

Rony Islam (from the Bike Talk interview): Yeah, and I think that another thing that is incredibly frustrating is that there was so much time and effort put into fighting for the Safe Streets infrastructure, like the Dickens Greenway. And now advocates have to fight before infrastructure is built, while the infrastructure is being built, and for the lifetime of the infrastructure, and making sure that it persists.

And I think that the lack of a citywide vision kind of contributes to this, and it lets folks fight back against Safe Streets improvements and have things rolled back. So now we're in a position where we're fighting for new pieces of infrastructure, and also fighting to maintain existing pieces of infrastructure, which is an incredibly taxing effort.

[At 31:00 in the podcast, I discussed the fact that it took 4.5 years of community meetings and advocacy to get the Dickens Greenway built. That's because there was next-level Not in My Back Yard opposition to the project from affluent neighbors, including a rather obsessive attorney, Edward C. Fitzgerald. I mentioned that I submitted a Freedom of Information act request to CDOT almost a month ago in an effort to find out exactly who was behind the campaign to the plaza back to drivers. I'm still waiting for a full response.]

RI: And I think another concern is, there's a lot of conversation about Lincoln Park right now, and this one plaza. But the folks who use Dickens as a greenway, or folks who use any greenway or any piece of infrastructure, not 100 percent of users live in the immediate vicinity of the infrastructure that's being built.

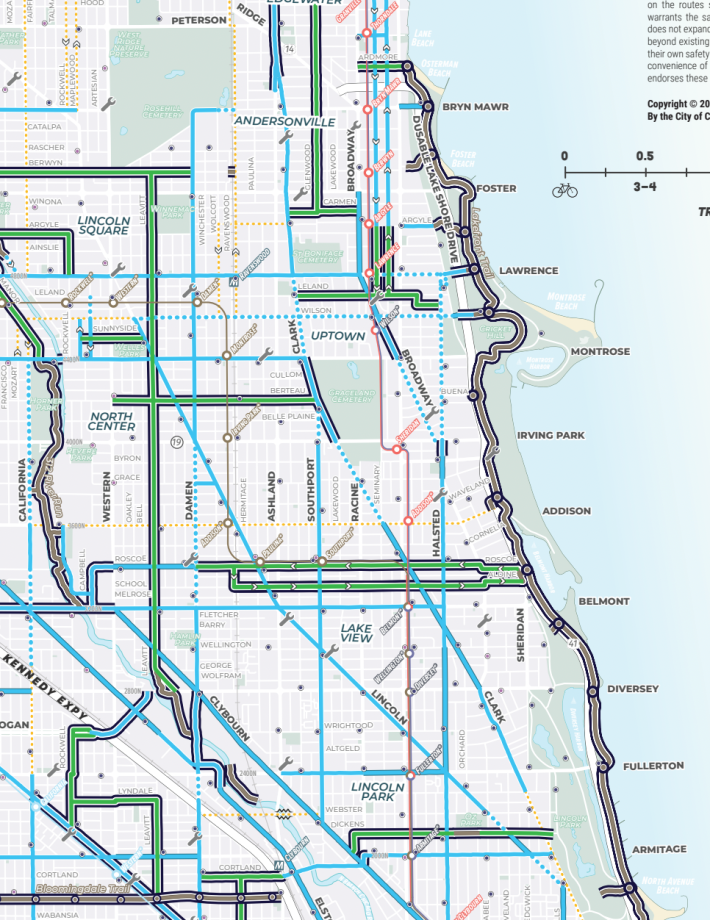

An example of this is, I live in Lincoln Square, and we have a greenway that goes through the neighborhood called the Leavitt Greenway. It currently terminates at one intersection at a [cul de sac, at Montrose and Lincoln avenues], and then continues after that intersection.

And the [47th Ward, represented by Ald. Matt Martin] is currently building a modal filter to allow cyclists to pass through that existing [cul de sac]. And when that is completed, there's going to be a nearly four-mile, continuous stretch of greenway that starts up north in a neighborhood called Bowmanville, and will go all the way south to the Chicago River. And this greenway will connect to Berwyn Avenue, which is another greenway, it will connect to Roscoe Avenue, which is another greenway, it will connect to the protected bike lanes on Belmont Avenue. And these are all really critical east-west connections that allow people to travel through our entire city in a low-stress way.

So although fights often happen at the community or neighborhood level, these are citywide impacts. That's why I think these kinds of conversations need to continue happening at the neighborhood level, but also need to escalate to, "What is our citywide vision for getting around, and how are we going to reduce traffic fatalities, traffic injuries at the citywide level, and not only having these conversations intersection by intersection, or street by street, or neighborhood by neighborhood.

MF: Yeah, and this is something that I'm trying to do as someone who does live in Lincoln Park. We know that the vast majority of driving trips are under three miles, and that's such low-hanging fruit. I will say that I cycle over a thousand miles a year. The vast majority of my cycling is within my neighborhood. I bike to work, I bike to drop my four-year-old son off at school and take him to appointments. I bike to the grocery store. I bike to the park. I bike to the Lincoln Park Zoo. And greenways like the Dickens Greenway facilitate those journeys for me. And I will often run into neighbors out biking.

It's almost been a year since the Dickens Greenway has been completed, so I assume that the Chicago Department of Transportation will be studying the impacts. And I can just tell you from my own observations as someone who uses the greenway almost daily, there are all kinds of people out there using this greenway.

Lincoln Park is an affluent neighborhood and oftentimes a small group of people who like to drive everywhere in our neighborhood will use that to be very loud and vocal about it. But 32 percent of people that live in Lincoln Park are car-free. The neighborhood has an average Walk Score of 94. There's three different 'L' lines, there's 12 different bus routes, there are over two dozen Divvy bike-share stations. This is a neighborhood that is really a pedestrian neighborhood. And so something that I'm trying to do is organize my neighbors to show up to these community meetings and say that people who live here want this, and people who live here will use this. And a lot more people are walking and biking than may be vocal at these community meetings.

And so we as a neighborhood need to organize, and we need to advocate for more and for better to impact us and to improve the life in our neighborhood. But also, to Rony's point, to create one link in a chain that will benefit people from all over the city of Chicago.

[Next, Fleck discussed her background in the neighborhood and with bike advocacy, and I talked more about the politics that led up to the current situation.]

RI: I think one thing people don't realize is, these pieces of infrastructure, they are saving lives. They're preventing people from getting hurt in car crashes. They're preventing car crashes from evening happening in the first place. And these are critical pieces of infrastructure that transform how people get around. They transform how people live their lives in their communities and strengthen neighborhoods. And it's not something that we should be fighting for for the rest of our lives. We should be able to rely on our local officials to try to make our neighborhoods the best places to live.

Listen to the Bike Talk podcast episode here.

Did you appreciate this post? Please consider making a tax-deductible donation, to help keep Streetsblog Chicago's sustainable transportation news and advocacy articles paywall-free.