This is the second entry in a series that also runs on the website A City That Works, a newsletter about public policy in the Chicago region. The first post was "No way to run a railroad: Governance is holding back transit in Chicagoland."

Last week I wrote about the fiscal cliff facing public transportation in Chicagoland, and the governance challenges that currently hold our transit system back. Due to the rise in remote work in the post-COVID era, ridership and farebox revenue are still down. Federal pandemic subsidies are running out, and the CTA, Metra, and Pace combined are facing a projected $770 million total budget shortfall in 2026. In the absence of a significant additional funding increase, next year the transit agencies will have to make major cuts and/or raise fares, leading to more ridership loss, a vicious cycle known as the "transit death spiral".

The financial side of this is challenging, to say the least. But the upside of this fiscal cliff is that it provides an opportunity to insist on major reforms to the in Northeast Illinois transit agencies. Done correctly, this could dramatically improve the quality and efficiency of public transportation going forward.

The primary question that has been debated over the last year is how the system should be governed. Right now, we have the three agencies that provide service, plus a fourth, the Regional Transit Authority, that is supposed to provide oversight. Even though the three systems provide service across municipal lines, the CTA is controlled by the City, and Metra and Pace are controlled by the suburbs. The RTA is hamstrung by a super-majority voting requirement that ensures either the City or suburban appointees can veto its decisions.

As a result, power lies with the boards of the service agencies, who jockey with each other for funding and authority. The result is poorly coordinated service, missed opportunities to invest in valuable capital projects like the Metra Electric line (a ready-made CTA route on the South Side), and less funding from Springfield and the feds than we’d otherwise get.

Now arriving: The Metropolitan Mobility Act

Then last year, and again this year, Senator Ram Villivalam (D-8th) and Representatives Eva-Dina Delgado (D-3rd) and Kam Buckner (D-26th) introduced versions of the Metropolitan Mobility Act in Springfield. The bill takes the most straightforward approach possible to reforming the system. That is, it eliminates the separate service boards, and consolidates them into a single Metropolitan Mobility Authority, responsible for transit in Chicagoland. The organization would be overseen by an 18-member board of directors, appointed as follows:

- 3 members appointed by the governor and confirmed by the Illinois Senate

- 5 members appointed by the mayor and confirmed by the City Council

- 5 members appointed by the Cook County board president and confirmed by board members

- 5 members (one per county) appointed by the boards of DuPage, Kane, Lake, McHenry and Will Counties

- 1 additional board member chosen as a board chair by the other 18 directors

The MMA board would make decisions based on a majority vote, rather than the super-majority system that has weakened the RTA. It also adds members provided the State, adding stakeholders who should prioritize the region as a whole. The bill also requires the new agency to develop a single integrated fare system, and establish performance standards for transit service.

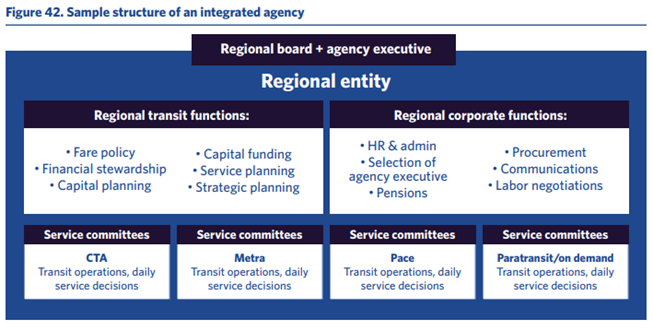

The resulting agency would look a lot like one of the recommended options in Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning’s Plan of Action for Regional Transit study.

The MMA would provide the cleanest break with the past. A single agency would be focused on maximizing ridership, rather than determining who collected which fares. The incentives to make duplicative investments would be eliminated. And a single agency that represents more than half the state’s population would have more clout to secure funding in Springfield and Washington, D.C.

The MMA would include some other important changes to transportation funding in the region. It would eliminates a current requirement that agencies fund 50 percent of their operating costs via fare revenue and other revenue sources, aka the farebox recovery ratio. That figure is untenable in the short term, given the post-COVID ridership drop. But it’s also been rendered kind of meaningless, as more and more costs, like security, have been carved out. In 2019, before the pandemic, the actual recovery share net of exclusions was only 39 percent.

In the long run, it might not be a bad idea to re-institute and gradually grow requirement back up to 50 percent. The ratio serves as a check on cost inflation and helps ensure transit investments are designed to actually boost ridership. It’s worth noting that world-class transit systems manage to cover a much higher share of their revenue from operations. The London Underground has a farebox recovery ratio of 130 percent (buses are at 65 percent). Munich had farebox recovery ratios of 70 percent as of 2010. And across much of Asia, farebox recovery ratios are regularly above 100 percent, and above 200 percent in parts of Japan.

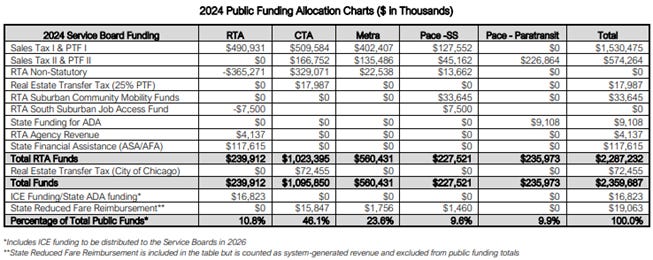

The MMA would also eliminate a complicated set of restrictions on the funding streams that determine how many dollars go to each service board. This would be progress both because it would enable more flexibility across agencies, and just remove an unnecessary administrative burden.

2024 Public Funding Allocation. Source: CTA FY 2024 Budget Book.

In addition to all that, there are three other reasons to expect more from the Metropolitan Mobility Authority.

1. Better managed capital projects

The MMA could give us a better shot at delivering capital projects faster, and at lower cost. Right now, that’s an enormous problem. The Red Line Extension is currently projected to cost over a billion dollars per mile. At that rate, it’s the last rail buildout the CTA will ever make. The RLE is particularly troubling, but this problem is endemic. The CTA’s recently finished Damen Green Line station cost $80 million and was delivered four years behind schedule.1 Meanwhile, Metra took 15 years and $34 million to build an above-ground infill station at Peterson and Ridge.

There are a lot of problems to unpack here, and we'll have more coverage of the Red Line Extension in the coming weeks. But one of the key factors identified by the experts at the Transit Costs Project is that U.S. transit agencies have outsourced key expertise to manage and oversee new construction.

Without enough engineers and technical experts at the agencies, engineering and contracting firms are given huge contracts without necessary guidance or oversight from transit agencies. This showed up clearly in the Peterson and Ridge case. Metra had lost control of the process, as change orders piled up and the small in-house Metra team found itself relying on contractors to manage each other and navigate complex city permitting processes.

The CTA and Metra should act yesterday to hire more in-house talent and rely less on external firms to do planning and oversight work. But that’s hard to do when agencies are doing a limited number of capital projects on an irregular basis.2 It’d be easier to justify a sizable in-house team in a larger agency overseeing a more stable set of capital projects across the agencies. Since the CTA is so much bigger than Metra or Pace, in the short term this would likely translate into a better resourced capital-projects arm for Metra. In the long run, it a unified agency could serve as a stronger foundation for better capital project delivery across the whole system.

A related problem identified by the Transits Costs researchers is that transit projects end up getting kicked around by other units of government. Sometimes this involves forcing transit projects to pay for other, ancillary benefits. In other cases, the intransigence of other players just drags out projects and drives up costs. In the case of the Peterson/Ridge station, both the Union Pacific Railroad and the City of Chicago’s Department of Water Management were extremely unhelpful as Metra tried to secure the necessary approvals and permits to complete the construction process.

A bigger, unified agency would have a better shot at fighting off these extraneous demands. The biggest beneficiary here would likely be Metra’s projects within the city. Infill stations or rebuilds would likely face fewer hurdles from City departments, which would no longer be able to write off commuter rail as a suburban project. And the freight railroads would have a harder time pushing around a larger agency that spoke for the region and had a direct line to the governor.

2. More density near transit

Transit doesn’t operate in a vacuum. More development near transit (both residential and commercial) creates more demand for service. Better service also makes it easier to justify more development. When residents move to areas near transit, their propensity to drive to work alone drops by a third. Analysis by CMAP finds that the impact of siting jobs near transit is even greater. But as the Metropolitan Planning Council notes, to the extent that the region has seen population and job growth in recent years, it’s been in areas with limited transit access.

There’s a lot of work to do here, and I’ve talked about corridor upzonings and a citywide land-use plan before. But the real solution to the region’s land use issues is at the state level, where policymakers are better able to balance localized objections with the broad social, economic, and environmental benefits of more housing.

The MMA includes a land use title that would start to point us in a better direction.3 It sets up an Office of Transit Supportive Development, and associated fund that could be used to support density via development funding, increased service, and technical assistance to help municipalities improve land use policies. Funding is conditioned on municipalities adopting transit-supportive overlay districts to increase density near transit, and the agency is also instructed to include land use rules in future strategic planning. Taken seriously, that could become a compelling tool. Over time, service levels could be optimized to serve communities that are making serious efforts to encourage transit-oriented development.

3. Overhead savings

A single agency should also be able to realize overhead savings. Some of that could be getting rid of duplicative functions and systems across Metra, Pace, and the CTA. How big these savings might be is hard to assess. The Civic Federation has cited an estimate from Slalom Consulting that there could be up $200-$250 million in savings associated with the consolidation. That report doesn’t appear to be public yet, so I can’t offer much of a perspective on how realistic it is.

That said, the RTA’s more limited reform plan (more on that in a minute), promises $50 million in savings via consolidation efforts. It’s not unreasonable to think that a more aggressive effort to overhaul the system and get rid of functions that are duplicative across agencies (or duplicative with CMAP’s planning functions) could generate substantially more savings. Given how much money the service boards are asking for, up to $1.5 billion per year, it’s entirely appropriate to be aggressive on this front.

Alternatives to the MMA don’t go far enough

Last year, the RTA proposed a less aggressive approach that keeps the separate service boards for the CTA, Metra and Pace. In addition to the cost savings mentioned above, the proposal would have the RTA set fares and an integrated fare policy; give it authority over capital projects and service standards; and give it the ability to review and approve budgets on a quarterly basis.

But as the Metropolitan Planning Council notes, the RTA already has authority over agency budgets. It might be a little easier to corral the agencies with more frequent reviews, but in the absence of reforms to the RTA’s supermajority voting rules, City appointees can block any budget cuts to the CTA, and the suburban appointees can block cuts to Pace or Metra. And by maintaining the different service boards, the leadership of each agency will ultimately be responsible to its own political masters, rather than the RTA.

The RTA’s plan doesn’t have legislative text yet, but a similar proposal has been floated by a coalition of labor groups, including the AFL-CIO and Chicagoland Federation of Labor. Their proposed legislation, dubbed United We Move, would also give the RTA control of capital project planning, along with the ability to withhold 10 percent of the service board’s budgets. It would also add state representation to the RTA board, lower the required 50 percent farebox recovery ratio, and create an RTA police force to beef up security.

If there’s one thing we learned through the CTA’s chronic staffing shortages over the last few years, it’s that the agency isn’t thoughtful enough about supporting and growing its workforce. Against that backdrop, it’s a good sign that labor is engaged. There are some important pieces of the bill. Adding state representation to the RTA board would increase the state’s involvement in transit issues and moderate city-suburban conflicts. Changes to farebox recovery ratio are also likely necessary in the short term.

But as its currently written, the United We Move legislation doesn’t go far enough to reform the current system. It has the same limitations as the RTA’s proposal (namely, keeping the service boards, and maintaining the supermajority voting requirement). It requires yet another study of the regional governance issues but explicitly rules out consolidating the service boards. In fact, it increases the size of the CTA and RTA boards, making governance efforts even more unwieldy.

The not-quite-enough effort is most obvious when it comes to security. The new RTA police force would be an effort to address critical safety problems on trains and buses. But it wouldn’t incorporate Metra’s existing police force, which means we’re in for another overlapping layer of security, rather than integrating operations across the agencies.

This is a solvable problem. Advocates of the MMA are looking for accountability and performance. That’s not in conflict with decent working conditions, salaries and benefits. In fact, the agencies need to be much more thoughtful about their workforces going forward. There should be a solution here that ensures labor has a seat at the table and protects the collective bargaining agreements, while moving us towards a consolidated agency that can deliver higher ridership and secure more funding.

Accountability for the CTA is a real risk

There are a bunch of reasons to like the MMA, but it comes with its own risks. The biggest concern is the potential impact on the City of Chicago. Today, the mayor appoints the majority of the CTA board and has to answer for its failings. That would't be the case if the CTA is part of a larger entity answerable to the City, County, collar counties and State. This has proved to be a serious problem in New York, where the governor controls the subway, but a large share of voters blame the mayor when thing go wrong.

In addition to an accountability deficit, the CTA could also face a funding problem. While Chicago accounts for roughly a third of the region’s population, the CTA accounts 85 percent of the region's transit trips. In a world where the transit agencies are all run by a majority suburban board, it’s possible that attention and resources gradually shift away from the CTA and the city. This is also a problem that has played out in New York. As the Eno Transportation Center study observes:

The composition of a board should correlate to the services it provides. In the case of the MTA board, suburban areas are disproportionately represented compared to urban areas relative to their ridership levels. This creates a tendency to overinvest in suburban capital projects, such as the Long Island East Side Access projects, while underinvesting in city infrastructure. It also may contribute to higher operating subsidies for suburban commuters relative to their city counterparts.

And while the CTA doesn’t play well with Metra and Pace, historically it has worked hand-in-glove with the City of Chicago.4 In the process, the CTA has benefited from billions of City Tax Increment Financing dollars for capital projects, including the Red Line Extension, Red-Purple Modernization, Damen Green Line Station and many more. It would be much harder for the City Council to fund major capital projects with Chicago taxpayer dollars if the MMA put the city on the back burner.

Done poorly, in the process of solving a serious but not life-threatening coordination problem between agencies, we could be creating a much bigger longterm challenge for the CTA. That's an agency with more than five times more ridership than Metra and Pace combined.

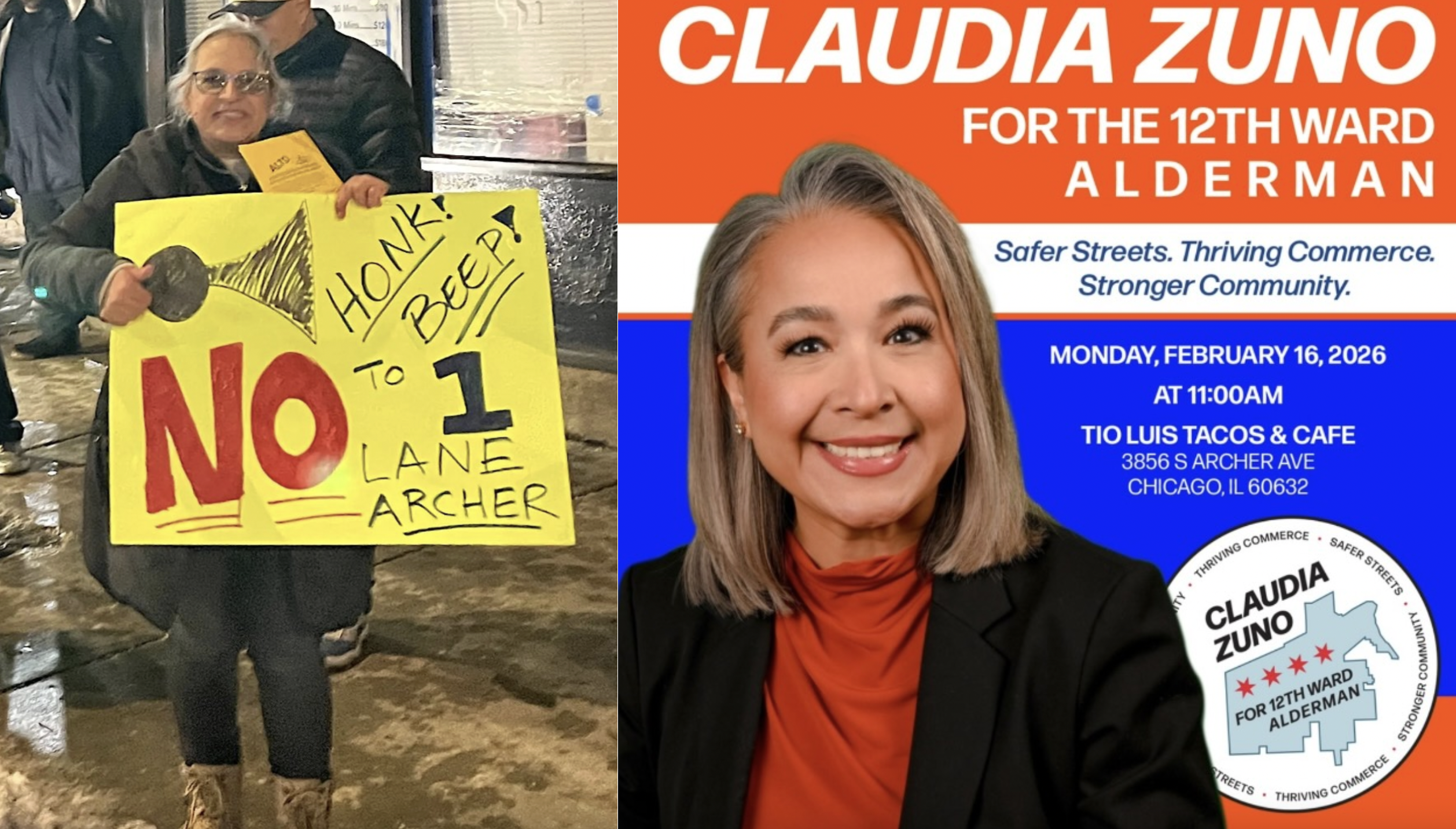

This might all sound academic, given how badly the CTA has been run in the last few years. But the Johnson Administration’s neglect of the CTA can and should be a real liability in the upcoming election. And challengers can credibly claim to be able to turn things around. If we instead punt CTA oversight to a 19-person committee with only five city appointees, we risk making the current problems permanent.

Solving for CTA accountability under the MMA

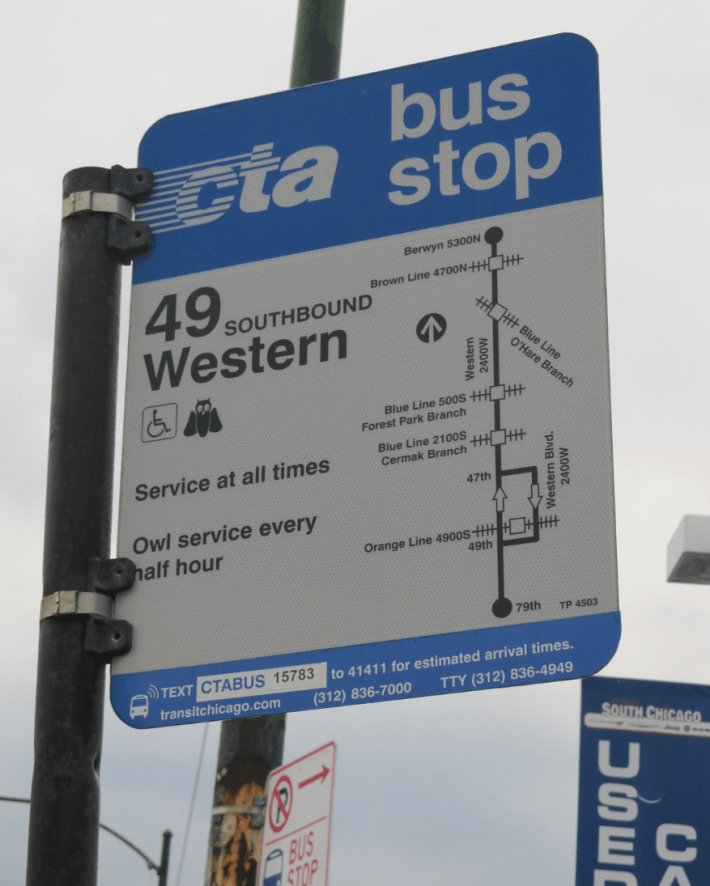

This problem can be addressed within the structure of the MMA. But we need to proceed carefully. Here’s the key test. Imagine a Chicagoan freezing on the side of Western Avenue because a scheduled CTA bus run never showed up. They're cursing our city's mayor under their breath because this "ghost bus" is going to make them late for work. How do we make sure that their anger is justified, because the mayor has the authority to help ensure reliable CTA service?

One potential solution, floated in the 2014 Northeast Illinois Public Transit Task Force Report, would be to have a board structured along the lines of the MMA, with a committee overseeing CTA operations comprised primarily of mayoral appointees. That committee would be tasked with overseeing CTA operations (i.e. delivering day-to-day service) and have confirmation power over the CTA president.5 That’s not a perfect system either, but it gets rid of the separate service boards, rolls all the non-operating decisions up to the larger agency, and still preserves enough mayoral control over day-to-day operations to keep the CTA accountable to the mayor.

The MMA’s accountability provisions, including requiring the agency to set and meet service standards, may also make it easier to determine how well the agency is performing and who is to blame. The bill even provides for performance-based compensation for managers. Done right, that could be a much more effective approach to accountability than simply dragging the CTA president before regular City Council hearings to get yelled at.

On the funding side, it’s worth noting that using some metrics the CTA is already getting the short end of the rail tie. While the CTA provided more than 85 percent of the transit trips, it only received 46 percent of the public formula funding in 2024. Of course, ridership isn’t everything. It’s more expensive to run transit in less dense suburbs; Metra and Pace both offer service in the city, and Chicago benefits greatly from having functional regional transit that enables suburbanites to commute into the city.6 But it would be a real problem if a larger agency started to deprioritize service in the city over time.

The solution isn’t to make insane demands for funding parity (that’s the trap we’ve been in for decades!) or re-create the strict funding formulas that put the transit agencies in a straitjacket today. But it might not be a bad idea to add some guardrails to the final bill to ensure that the CTA and City can’t get hosed.

A rule preventing a more than 40 percent divergence between an agency’s share of ridership and its share of regional public funding, for example, would help protect CTA service. It would also encourage City Hall to continue to put in discretionary funding in without fears that it would leak to the suburbs.7 This is another reason to slowly bring back the farebox recovery ratio. The CTA does a better job covering the costs of rides than Metra or Pace, so a gradually rising ratio would keep the combined agency focused on its most cost-effective urban service.

Mergers are hard

Merging the agencies won’t be an easy logistical task either. Consolidation amounts to ripping off a band-aid, but other regions have done this effectively – especially Boston, which has the most successful approach to regional service of any of the regions identified in a 2014 study of transit governance systems by the Eno Center for Transportation.

The good news is that the MMA gets rid of the competing board members immediately upon going into effect, with the current RTA board in charge until new board members are nominated. But it could likely move faster to actually integrate the agencies. Right now, the legislation gives the new authority two years to set up an Integration Management Office to oversee the consolidation, which seems far longer than necessary. But until we move forward with consolidation, we’ll continue to grind along with a transit system that functions less effectively than the sum of its parts.

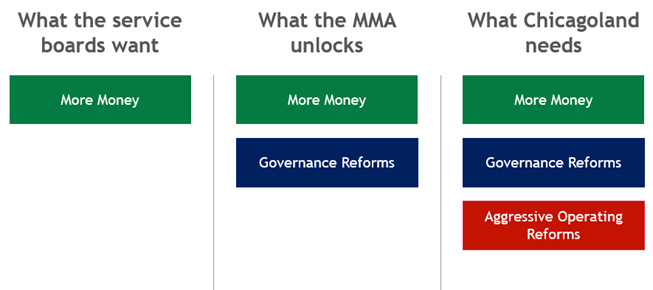

Governance reforms are necessary but insufficient

That said, while consolidation removes key barriers to better system performance, it doesn’t guarantee better outcomes. The MMA would provide a chance to shake up an ossified management structure. A newly constituted agency would need to seize that opportunity to force its various operating divisions to coordinate service, share resources (in the case of the Metra Electric Line), invest in in-house capacity, and push for better land use. The MMA legislation does require the establishment of regional service standards, but it’s an open question how aggressive those standards will be – and how capable the newly constituted agency will be of actually meeting them. Governance reform is a great place to start, but it’s a really bad place to stop.

The State’s involvement in this is every bit as important as its support for funding and governance. An empowered, high-performing agency with a mandate to drive critical transit reforms will only emerge if the State sets the expectation that similar performance under new management is unacceptable.

Or, as the Eno Center report observed: “[T]he State seems to believe that its role is to reorganize the transit agencies’ governance structures, instead of actually working towards improving performance outcomes or funding. This unusual State role contributes to the many challenges facing Chicago transit.”

While I’ve talked about some key operating changes that are required here, it’s beyond the scope of this piece to outline all of the operating changes lawmakers should push for. Some of that work may require legislation beyond the MMA. The other key question is the personnel named to a new agency’s board, and the mandate a new Executive Director might have. Those are the sorts of picks that will set the tone for a new agency: more of the same, or a hard-charging organization with a mandate to deliver superior service. I’ll spend more time on these issues in future pieces.

The next few months of wrangling over funding and governance reforms will be a huge political lift. But if we’re already going to find hundreds of millions of dollars and blow up the current agency structure, the added juice of real operational reforms is well worth the squeeze.

A massive opportunity

Like a lot of things around here, our public transit system is an incredible asset that delivers less for residents than it could. The current fiscal cliff presents a once-in-a-generation opportunity to address the roots of our current challenges. The proposed Metropolitan Mobility Act is a good start. But it needs two adjustments: mayoral accountability for CTA operations, and a gradual reinstatement of the farebox recovery ratio.

With those changes, the MMA could be the foundation of a much stronger transit network going forward. If it’s paired with additional funding and aggressive operating reforms, we could deliver on the frequent, safe, and cost-effective service that riders deserve.

1

The Damen Green Line station was also plagued by elevator outages almost immediately after the ribbon cutting.

2

Re: agencies doing a limited number of capital projects on an irregular basis, there’s a vicious cycle here: higher costs mean fewer projects, and fewer projects make it harder to justify in-house capabilities.

3

Streetsblog Chicago Cofounder and Advisor Steve Vance, who also runs the real estate data website Chicago Cityscape, has a good full summary of the provisions, "What the proposed MMA Act is offering land use policy," on his personal blog Steven Can Plan.

4

Yes, I know getting recently retired CTA President Dorval Carter to attend City Council hearings was like pulling teeth. But over the longer run the relationship between the CTA and the City has been extremely close, and making policy based on a recent outlier is a recipe for bigger headaches down the line.

5

In this version, the committee overseeing CTA operations might need termination powers as well.

6

You can also pull a Pate Phillip and run the math in reverse: Chicago accounts for just one third of the population in the service area, but the CTA gets almost half of the formula money. The point isn’t to do this either. It’s to move to a system that more flexibly moves funding to where its needed most, while addressing the unique strengths and needs of a dense urban city.

7

If you don’t want to do this [a rule preventing a more than 40 percent divergence between an agency’s share of ridership and its share of regional public funding] by agency because coverage areas may change in a more unified system, you could do the same thing based on the number of trips beginning inside the city, the county and the collar counties. That might serve as a stronger impetus for Metra to beef up intra-city service.

Did you appreciate this post? Streetsblog Chicago is currently fundraising to help cover our 2025-26 budget. If you appreciate our reporting and advocacy on local sustainable transportation issues, please consider making a tax-deductible donation here. Thank you!