Check out Luke Nelis' letter on the Sun-Times opinion page here.

Yesterday, lifelong Logan Square resident Luke Nelis had a letter to the editor published on the top of the Chicago Sun-Times opinion page, "Bike safety isn't a one-way street. Don't put it all on drivers."

Nelis isn't exactly a rocket scientist. No, seriously, his LinkedIn page says he has experience with "airline operations, aviation consulting, airport operations and consulting" and as a "professional pilot." So I'd never try to win a debate with Nelis over aviation policy.

But when it comes to creating safe, efficient, environmentally friendly, and enjoyable streets, I think Nelis has a thing or two to learn. It also would have been good if the Sun-Times had done a better job of fact-checking a statement or two in his letter before publication.

That said, I don't think Nelis' letter is complete garbage – it actually includes some reasonable points. So let's take a close look at his entire statement, in italics, with my responses in standard text. I've added links to his piece to help illuminate what he's talking about.

Bike safety is not a burden to be carried by drivers alone and must be shared by the city, bikers and drivers. Proponents of “Vision Zero” talk about reducing bike fatalities, but what is their plan to address the biker’s role in bike safety? What does Vision Zero do to address bikers blatantly ignoring traffic signals, weaving between cars and changing lanes without looking or signaling?

Bike riders treating a stop light like a stop sign, or a stop sign like a yield sign, is nicknamed the "Idaho Stop," because this behavior is legal in the Gem State. One or both of those practices are currently allowed in eleven other U.S. states. DePaul's Chaddick Institute published a study that found this behavior is nearly universal in Chicago, and said Illinois municipalities should consider legalizing it.

The DePaul report even mentioned a 2007 U.K. study that found that in London, turning truck drivers were much more likely to fatally strike women on bikes than men. That seemed to be due to women being more likely to obey the letter of the law by waiting for a green at stoplights, and get caught in a turning motorist's blind spot.

Still, if a person on a bicycle blows through a stop sign or red light without checking for, and stopping for or yielding to, cross traffic, that's dangerous for themself and other road users, not to mention obnoxious. And Nelis is correct that "weaving between cars and changing lanes without looking or signaling" while riding a bike is hazardous and inconsiderate.

It’s easy to ignore these daily realities in Chicago and blame drivers for safety issues, but a biker’s ultimate role is to maintain his or her own safety and any biker who undermines that hurts the entire biking community.

Like human beings using any other transportation mode, people on bikes have the potential to behave responsibly or recklessly. And I agree that, besides staying alive and not hurting anyone else, a great reason to be careful and courteous while riding a bicycle is to help other road users view cycling in a positive light. That can help create a "virtuous cycle" of good behavior on our streets.

But let's remember that there's exponentially more chance of doing harm when you're piloting a two-ton vehicle with poor sight lines at 30 mph or more, than a 20-pound bike with nearly 180-degree vision at a fraction that speed. That helps explain why, while drivers struck and killed 31 pedestrians and five bike riders on Chicago streets in 2023, I've seen no evidence that a person biking has fatally struck a pedestrian in our city, ever.

The city shares a role as well. When the city installs bike lanes, it needs to take other measures to keep traffic moving and not accept gridlock as there’s been on Belmont Avenue across Avondale, and Logan Boulevard after Ald. Daniel La Spata (1st) turned it into a two-lane road.

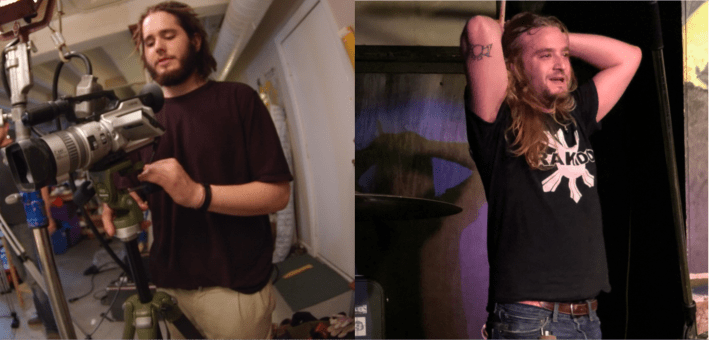

Logan Boulevard east of Rockwell Street did get a road diet with protected bike lanes a few years ago, partly in response to the deaths of two people cycling. In 2008, a motorist struck and killed videographer Tyler Fabeck, 22, on his bike there. About 13 years later, in May 2021, a driver fatally struck “School of Rock” drummer Kevin Clark, 32, while he was cycling through the intersection.

It’s not only about pouring concrete; it’s about a comprehensive community-driven plan to make bikes and cars mesh together, such as incorporating the re-timing of traffic lights, installing turn lanes and programming pedestrian scrambles — temporarily stopping traffic to allow pedestrian movement — to aid traffic movement.

Sure, pedestrian scrambles are good idea, and Chicago has exactly one of those, installed in May 2013 at Jackson Boulevard and State Street in the Loop. So I'd definitely support installing more of them, say at the Logan Square traffic circle.

It also takes commitment. If the city is going to build bike lanes, it needs to commit to maintaining them. That means clearing trash and snow. Logan Boulevard has seen standing water in it since the addition of bike lanes because trash that accumulates under the concrete blockers for bike lanes blocks the sewers. LaSpata was quick to build these lanes, but does not appear to have a commitment to maintaining them.

I agree 100 percent that the City needs to do a better job of keeping protected bike lanes of broken glass, garbage, and snow. Thankfully the Chicago Department of Transportation has recently started using miniature snowplows and street cleaners to do this work.

Thank you to CDOT and their bike lane-sized snow plows for promptly clearing our new Clark St protected bike lanes!! ❄️🚲 pic.twitter.com/ye88lsGyCu

— Alderman Matt Martin (@AldMattMartin) January 13, 2024

And there are annoying flooding problems with a few of Chicago's new protected bike lanes. But, contrary to popular belief, it's generally not the bikeways themselves, or drains clogged with trash or leaves, that are causing the problem.

The real reason for flooding appears to be "rainblockers," devices that are intentionally used to limit the amount of rainwater entering the city's sewer system, to prevent it from backing up. Read the City's explanation of the strategy here. So even before the curbside PBLs were installed, the pavement under cars parked against the curb would often flood.

So yes, CDOT needs to find a solution to the bikeway maintenance and flooding issues, and they're starting to install raised bike lanes more often, which are less prone to these issues. But Nelis' statement that "trash that accumulates under the [curb protection] for bike lanes blocks the sewers" on Logan Boulevard is probably incorrect. The Sun-Times should check with the authorities about this and run a retraction if necessary.

Drivers see fees and fines perpetually increasing, slower traffic and fewer lanes as bike lanes increase. It is high time that bikers share the burden and pay fees like drivers to help fund community-designed comprehensive improvement.

Bike riders don't pay sales, income, and property taxes that help fund car-centric projects like the recent $800M-plus Jayne Byrne Interchange Expansion in the West Loop? There's also the fact that when you choose to ride a bike instead of driving you're helping reduce societal costs associated with car crashes, congestion, pollution, and wear-and-tear on roads. And in some cases, initiatives that benefit bike riders are completely funded by fees paid by cyclists, such as the nearly $1M in Divvy bike-share revenue used to bankroll the Dickens Greenway in Lincoln Park.

Drivers have an outsize role in road safety. That means put down the phones, share the road, look before opening doors and lead the charge to a comprehensive plan increasing citywide street safety. Chicago has come a long way in making the streets safer for bikers, and I feel confident taking my children on bike rides. But we can only become a bike haven like Amsterdam together, with all stakeholders involved.

This paragraph actually isn't bad. But if Luke Nelis actually wants Chicago to be more like Amsterdam in terms of bike safety, he has to be willing to commit to what the Dutch did decades ago. That means less driving, more walking/biking/transit use, and less public space wasted on moving and storing large metal boxes. And we need better bike education and infrastructure, and traffic laws that prioritize the safety vulnerable road users over the convenience of motorists.

Check out Nelis' letter on the Sun-Times opinion page here.

Did you appreciate this post? Please consider making a tax-deductible donation, to help keep Streetsblog Chicago's sustainable transportation news and advocacy articles paywall-free.