These aren't golden years for the Chicago Transit Authority. The agency's problems with staffing shortages, unreliable and frequent service, safety, and cleanliness are well documented. Many politicians and transit activists are arguing that CTA President Dorval Carter Jr. should be fired.

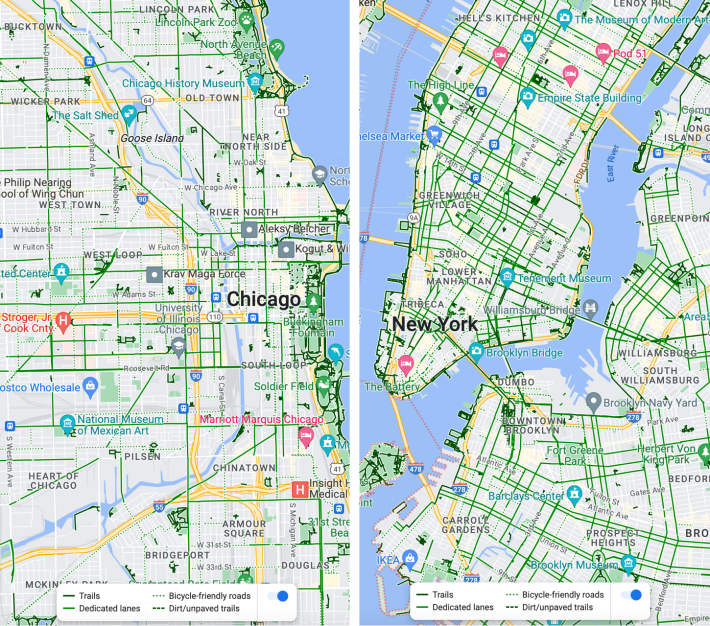

And while I strongly disagreed with a recent People for Bikes report that found Chicago is one of the very worst large U.S. cities for biking, we have been falling behind peer cities in building a connected, protected bike lane network. (The relatively large number of protected bike lanes built here in 2023 suggests we might be getting back on track.)

Now, my Streetsblog New York City colleagues might think my recent impressions of the Big Apple are a little rose-colored. But during a visit for advocacy group Transportation Alternatives' Vision Zero Cities conference (read my writeup of the downtown congestion pricing panel here), I was impressed by the state of local biking, transit, and more. Or at least it seemed good compared to the current situation in Chicago.

This was my first time hanging out in New York since the latest Streetsblog Network editor meetup in 2014. Granted, my recent visit was focused on Manhattan, so I didn't get much of an impression of what's going on in the outer boroughs. But here's what I saw.

Public Transportation

I started my visit at LaGuardia Airport in Queens. Now, one of Chicago's strengths is that we are one of the only U.S. cities with two airports served by rapid transit lines. LaGuardia does not have train access, although transit improvements are planned.)

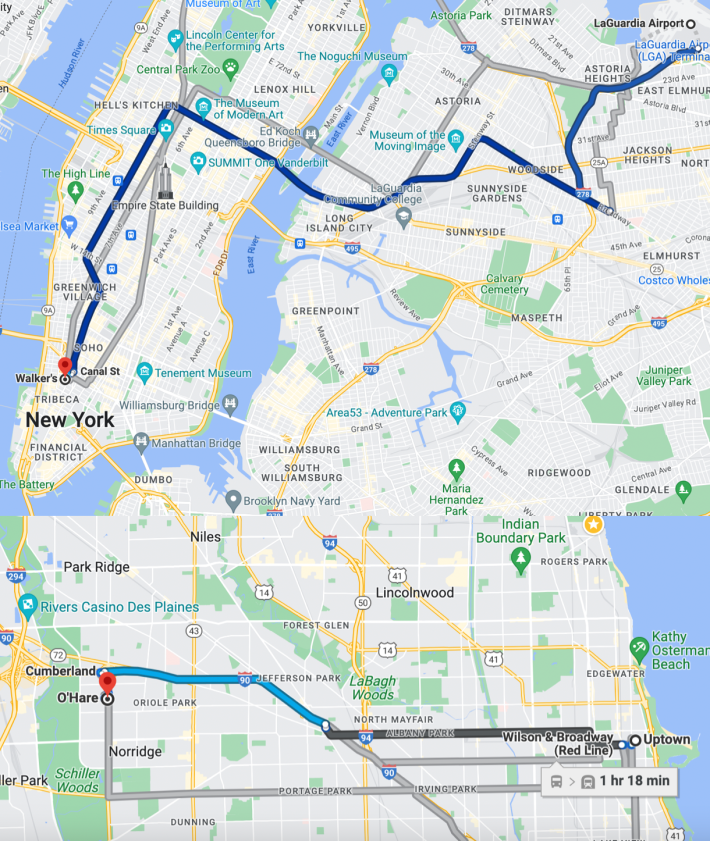

Still, the public transportation I took from LaGuardia to meet up with Streetsblog editors at a tavern in the West Village, near the network's NYC HQ, was pretty good. I went downstairs from the baggage carousel to catch a Q70-SBS Laguardia Link bus, which provided a no-charge, nonstop ride to the Jackson Heights Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) station.

At Jackson Heights I bought an MTA card and then walked down a couple flights of stairs to catch a Manhattan-bound E express train. This fast, clean ride took me the Canal Street station, a short walk from the bar.

The whole 10-mile trip, leaving around 7 p.m. on a Wednesday, took about an hour. That's a little faster than my usual 1:15 to 1:30 bus + Blue Line trip from Chicago's Uptown neighborhood to O'Hare, which covers roughly the same distance. ("Your ride from the airport to the train to the bar was exceptionally lucky," Streetsblog NYC editor Gersh Kuntzman told me. "Normally, add at least 15 minutes to your time."

Granted, my impression of New York subway conditions on this trip was probably skewed a bit by the fact most of my many train rides took place in more affluent parts of town. The conference took place at New York University in Greenwich Village, and I was graciously hosted by some old friends who live a mile south. And I rarely got uptown from Central Park.

Still, trips involving CTA trains that pass through downtown or fancy neighborhoods often involve "ghost trains" that are scheduled but don't materialize when scheduled due to staffing shortages. Loop subway stations tend to be unattractive and dingy, and there's often litter and/or cigarette or marijuana smoke in the railcars.

In contrast, I never encountered major delays or cancelled service on the New York subway, and runs usually arrived more frequently than even pre-COVID 'L' service. That's to be expected in a city where less than half of households own cars, compared to almost three-quarters in Chicago. But again, maybe I was just fortunate during my NYC visit when it came to avoiding service disruptions.

And the MTA stops I visited on this trip were generally fairly clean, and often had interesting station design and public art. Litter was rare in the rail carriages I rode in, and smoking was a non-issue. For what it's worth, I did see a couple of turnstile-jumping incidents.

One perk I noticed at the MTA's 33rd Street station by Manhattan's Koreatown, a stop that also serves PATH commuter rail trains to New Jersey, was public restrooms available to rapid transit customers. Those are nonexistent on the CTA, although the system's riders and employees have frequently requested them. The 33rd Street bathrooms are only open from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m., but the men's room was reasonably sanitary.

Public restrooms in MTA stations are "not common, but they are slowly coming back," Gersh Kuntzman told me. He added that all of the bathrooms were closed during the pandemic.

Bike infrastructure

I frequently rode New York's Citi Bike, which like Chicago's Divvy bike-share system is run by Lyft, although Divvy memberships aren't valid on Citi Bike. The equipment is very similar, although many NYC stations are much larger than their Windy City counterparts. But unlike e-Divvies, electric Citi Bikes don't have built-in cable locks (presumably due to NYC's more aggressive bike thieves) and can only be parked at stations. I learned that the hard way while running late for a dinner appointment.

Our city's Chicago, Bike Grid Now! advocacy group is tirelessly pushing for a citywide low-stress bikeway network. But least in Manhattan and some other cycle-centric parts of town, NYC basically already has a bike grid, now. In stark contrast to when I last visited in late 2014, just about all of my riding took place on protected bike lanes. (Gersh responded, "This is far less common outside the wealthiest neighborhoods in town.")

In June CDOT announced its plan to add concrete protection to all of Chicago's existing protected bike lanes, inspired by a similar initiative announced four months earlier in New York. And in the Chicago Cycling Strategy document released last April, CDOT stated that most new bikeways would be low-stress protected main street lanes or Neighborhood Greenway side street routes.

"Moving forward, concrete curbs will be the default barrier utilized when new protected bike lanes are installed," the document said. Indeed, many or most new 2023 bikeways were partially or fully concrete-protected bike lanes, which jibes with the increasingly popular bicycle activist slogan about bike lanes, "Paint is not protection."

Many of NYC's parking-protected bike lanes I saw had little or no concrete, and in many cases there weren't even flexible plastic posts separating bike riders from parked cars. And yet I rarely noticed motorists driving, standing, or parked in the curbside bikeways, which is common in Chicago. In addition to heavier bike traffic, I attributed that to the lanes usually being painted green, distinguishing them from car lanes.

I asked Gersh whether New York's quick-and-cheap protected lane strategy could be credited for the city's recent PBL boom. For example, about four miles of my Citi Bike ride from NYU to a Hungarian restaurant (we don't have any of those in Chicagoland) were on a largely paint-and-post protected lane on First Avenue. I'm pretty sure there are no continuous PBL streets any where near that long in the Windy City.

Bur Gersh suggested that my relatively hassle-free experience riding New York's protected lanes might have just been good luck. "The city’s parking protected bike lanes work OK, but there are often daylighting issues [parked cars blocking motorists' views of people in crosswalks], such as drivers that park too close to the curb, which is legal in the city," he said. "The city tries to prevent this by painting the corners in light brown paint, but it never works. The posts [delineating the no-parking area] always get knocked down by drivers parking on the brown zones."

"Virtually every painted bike lane in a commercial zone is blocked by double-parked cars," Gersh added. "They are effectively useless and also put you in the door zone."

He said that while New York has many green-painted bike lanes, these are generally not physically protected. "They’re merely green."

Dining areas in parking lanes

Chicago experimented with "Curbside Cafes," seating areas for patrons of restaurants and bars locating in car parking spots, in a few locations, but the pilot quickly petered out. Problems included the facts that the city's hated 75-year parking meter contract requires the parking concessionaire to be compensated for lost revenue, and that the seating areas had no weather protection.

Meanwhile, parking spot seating seems to be everywhere in eatery-heavy New York districts thanks to the city's Open Restaurants program. Much of it is nicely designed, and it often has good weather protection, which means that it can potentially be used most of the year, in all but the most challenging weather.

New York merchants seem very happy to swap a few car spots for a whole lot more seating for paying customers. Sure, New Yorkers are less likely to drive to a restaurant or bar (which you shouldn't do anyway) than Chicagoans. But the Windy City should definitely try doing this again, with designs that provide more shelter from the elements.

"While most of the outdoor dining set-ups are well protected from the weather, starting in 2025 that won’t be the case," Gersh noted. "The existing structures are grandfathered in until the end of 2024. Then we get newer, lighter and much less weatherproof outdoor dining."

So, yes, my POV may be a bit Pollyanna-esque. But I left New York with a positive impression of its current transit, biking, and outdoor dining conditions.

And while Chicago outdoes NYC on several culinary fronts (hotdogs, tacos, Italian beef, etc.), you can't beat New York bagels. Fortunately after I got home I was able to scratch that itch at this place in Lakeview that imports them.