In December 2021, the Tribune looked at the state of Illinois' plans to widen expressways to downtown Chicago as "solutions" to traffic congestion. But history shows this approach only results in more driving, pollution, transportation inequities, and traffic jams.

"Increased investment in fast, reliable public transit is clearly a more effective, sustainable, and equitable solution," then-Active Transportation Alliance spokesperson Kyle Whitehead told Streetsblog at the time. "Congestion pricing, such as charging drivers a toll for entering the Central Business District during peak hours, should also be considered if officials are truly interested in long-term, sustainable solutions."

That's accurate of course, but over the years our city has made little progress on implementing congestion pricing, which would help make CTA bus service quicker and more dependable, as well as improving safety for all road users. Here's a quick review of what's happened in Chicago.

In the late 2000s, then-Mayor Richard M. Daley proposed a congestion parking program that would have been funded by the second Bush administration. But the city of Chicago missed a deadline to raise downtown meter rates, so the Federal Transit Administration rescinded the $153M grant. Daley's successor Rahm Emanuel tried a similar strategy again in the early 2010s.

In the late 2010s the Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning proposed congestion pricing on Chicagoland expressways, and the Illinois Department of Transportation expressed interest in doing that on the Stevenson Expressway.

In 2019 under then-Mayor Lori Lightfoot, the city of Chicago proposed a new tax on ride-hail trips ending at or beginning in the downtown area, which it dubbed "congestion pricing." Thankfully, that passed.

But there hasn't been much talk of a central-area Chicago congestion fee from politicians since then. The exception that proved the rule was progressive alder Matt Martin (47th) floating the idea during city budget talks in November 2020. Meanwhile peer cities have been leaving us in the dust in that department.

At this week's Vision Zero Cities conference in New York City, hosted by local sustainable transportation advocacy group Transportation Alternatives at NYU, I got a preview of how Chicago could benefit from a robust congestion pricing initiative. In the panel discussion Driving Change: The Case for Congestion Pricing, experts from NYC, London, and Montreal discussed how their hometowns are rethinking public space and deprioritizing downtown driving.

The panel included Betsy Plum from New York's Riders Alliance transit advocacy organization, Clare Sheffield from the London office of the ARUP urban planning firm, and Charles de la Chevrotière from the "paramunicipal organization" Agence de mobilité durable Montréal. Consultant and board member with the New York MTA, the regional transit agency Midori Valdivia moderated.

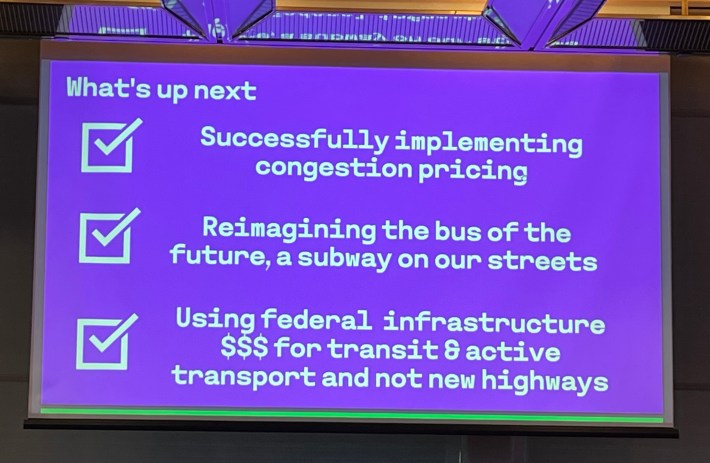

As Valdivia explained at the start of the talk, New York City’s congestion pricing program hopes to reduce traffic in Manhattan’s central business district, and also raise $1 billion a year for the the MTA. It became law in 2019, but it was delayed for several years by the Trump administration. But in 2023, the Biden administration gave its final sign-off, paving the way for congestion tolling to begin, which is now expected to start in mid-2024.

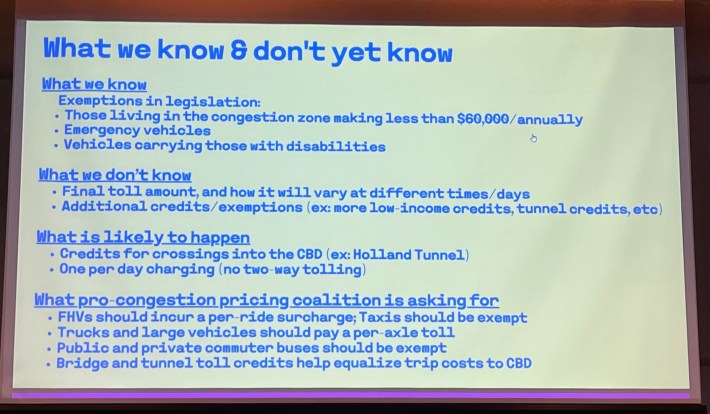

Plum elaborated on the NYC situation. The immediate challenge right now is that many drivers across multiple constituencies are seeking exemptions from the still-to-be-determined toll. Exemptions for any group, of course, will raise the toll for everyone else.

"There will probably be credits for those coming in from New Jersey and those crossing already-tolled entries to the Central Business District," Plum said. "And we have a pro-congestion pricing coalition, a bunch of different advocates across the transit, environmental, disability justice, immigration macro, housing all these different spaces that have come together. We've basically said, for-hire vehicles should just have a once-per-ride surcharge and yellow taxis should be exempt from the congestion toll, we have said that trucks and larger vehicles should pay a per-axle toll... and then we'll have public and private commuter buses being exempt."

"This is really thinking about the New Jersey Transit bus, and then bridge-and-tunnel toll credits should be equalized across the region," Plum added. "We don't want negative effects from this, and so we've been pushing for that. Ultimately, though, continuing to keep riders and the idea of transit justice at the core of this is super-important to a successful roll-out."

"Congestion pricing is not the be-all, end-all of good transportation policy," Plum concluded. "And so [there's] how we make sure that this program and policy is as successful as possible, the things we do around it to make its Day One successful. But then everything we do from the freed-up space on the streets as we've heard, and will learn more about, what London did, that is a part of our future and the dream that riders have, is that space will be used for buses and that we can really see a culture change in our city, state, and country."

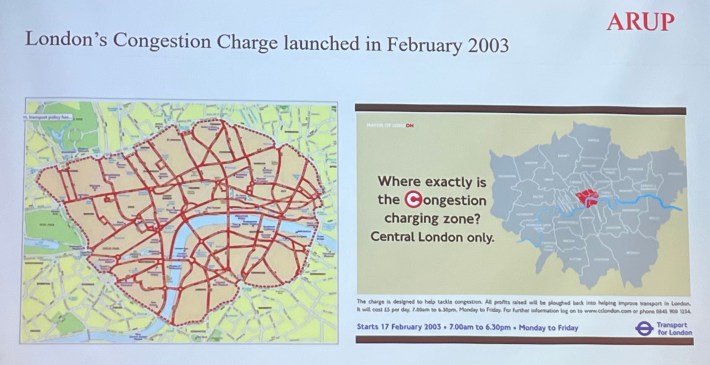

Sheffield has a background in social science, and in 2004 she took a job working on the Central London congestion charge, which had started in February 2003, working on research and policy development. She noted that the UK pulled off congestion pricing, even though the country is much more car-centric than transportation-friendly nations like the Netherlands and Denmark. "My message is, it can be done" even in relatively car-oriented places, she said. "Did it work? It did work! That's my short answer."

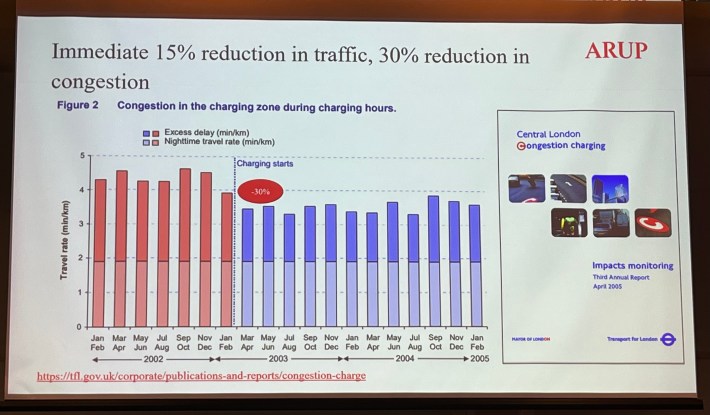

Sheffield said that from from day one of the congestion pricing, London saw a 15 percent reduction in traffic and a 30 percent reduction in congestion, and those levels have been sustained to this day.

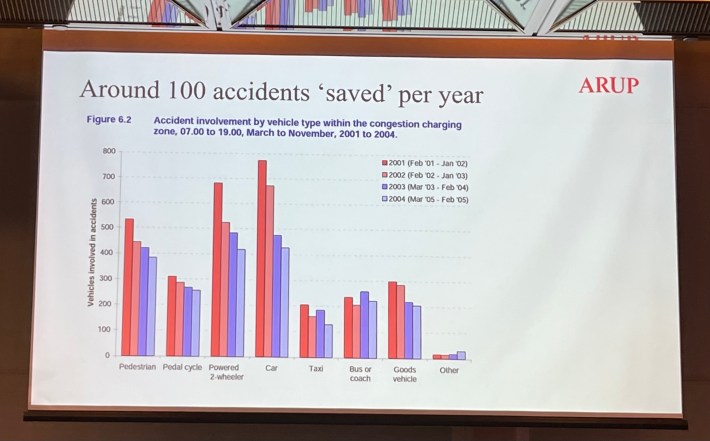

She also said there were dramatic safety benefits. A study estimated that about 100 crashes were avoided each year within the congestion pricing zone, and 140 citywide. "Basically, the roads were getting much, much safer all over the city."

Sheffield added that, thanks in part to congestion pricing, there was a very sustained decreased in traffic casualties in London. In 2005-9, the baseline for a study there, there were about 5,000 people seriously injured or killed, and that has been reduced by 44 percent to-date.

So making robust congestion pricing happen in downtown Chicago will take teamwork by advocacy groups, and some political courage from lawmakers. But the numbers make it clear the work would be worth it.

Did you appreciate this post? Please consider making a tax-deductible donation.