The Regional Transportation Authority is planning to use $486.2 million in transit funding from the latest stimulus bill to support transit services to “to the places and people across the region who most need transit” during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Based on the research shared during the RTA’s January 21 board meeting, this would mean Chicago, Joliet, Aurora, Elgin and Waukegan, as well as a handful of clusters in the south, west and northwest suburbs. It would be up to the individual transit agencies the RTA oversees to decide exactly how they would use the cash, and what service changes, if any, they would make.

The research data suggests that the CTA would benefit the most from the new stimulus funding, since it serves a decent portion of the areas in question. Like Metra and Pace, the CTA has been using federal funding from the original CARES Act stimulus bill to plug its budget deficit, but CTA president Dorval Carter has previously warned that his agency will run out of that funding faster than Metra and Pace.

The RTA will release a more concrete plan during its February 18 board meeting. The public will have until March 5 to give feedback. The RTA board will vote on the final version of the plan during its March 18 meeting.

As RTA officials explained during last week, the stimulus funding won’t completely fill the transit agencies’ budget gaps. The RTA will continue to lobby for further federal and state funding, as well as research other revenue sources – a possibility that it is cautiously optimistic about now that Joe Biden is president and people are getting vaccinated, which could mean more employees commuting to work.

Current ridership situation

One of the factors the RTA looked at when figuring out where the funding would go is transit ridership and transportation use in general. It found that, between February and November 2020, vehicle use in the Chicago area has declined by 25 percent, and people tended not to travel as far from their homes as they used to. Many areas – including significant chunks of the suburbs, as well as the Loop and its surrounding neighborhoods – saw transportation use dip by as much as 78 percent. However, in some census tracks, mostly on Chicago’s South and West sides and further-flung suburbs, transportation use actually went up due to increased commuting by essential workers.

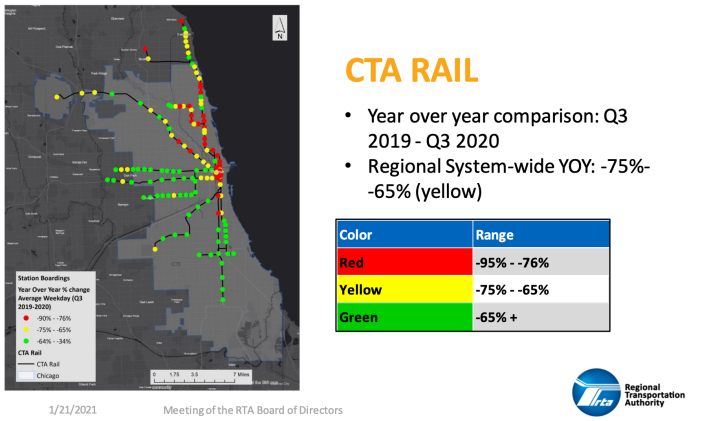

Overall transit use has been gradually increasing since April, although as of November it was still less than 50 percent of pre-pandemic levels. While the overwhelming majority of transit services saw ridership declines, some fared better than others.

In Chicago, ‘L’ stations on the South and West sides have seen smaller declines than routes serving other parts of the city. CTA buses saw the brunt of the declines fall on the routes serving the Loop, the University of Chicago’s Hyde Park campus and, interestingly, routes serving Evanston and Skokie. Pace similarly saw the biggest declines in express and local routes serving Chicago, as well as the routes serving suburbs directly north of the city.

Metra, which has a largely white-collar, suburban ridership, has seen the most dramatic ridership declines during the pandemic, and made deeper service cuts than CTA (which basically didn't cut service at all) and Pace. However, the officials officials noted that, as I’ve reported in the past, the Union Pacific North, Rock Island District and Metra Electric lines fared better than others. Peter Kersten, the RTA’s Strategic Planner, noted that RID and Metra Electric have more stops within the Chicago city limits than other Metra lines. He didn’t have an explanation for why the Union Pacific North has been doing better, but one possible explanation is the fact that Union Pacific, which operates the line for Metra, has been refusing to collect fares onboard during the pandemic.

Mapping the critical needs areas

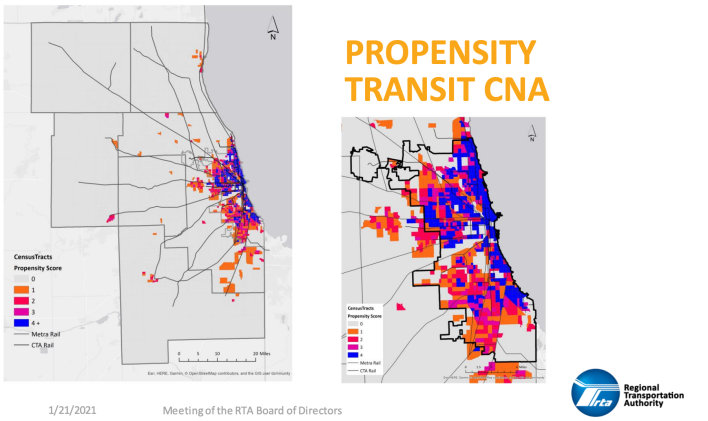

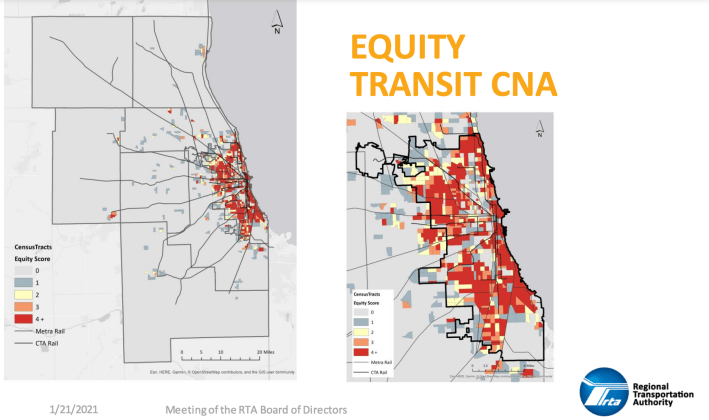

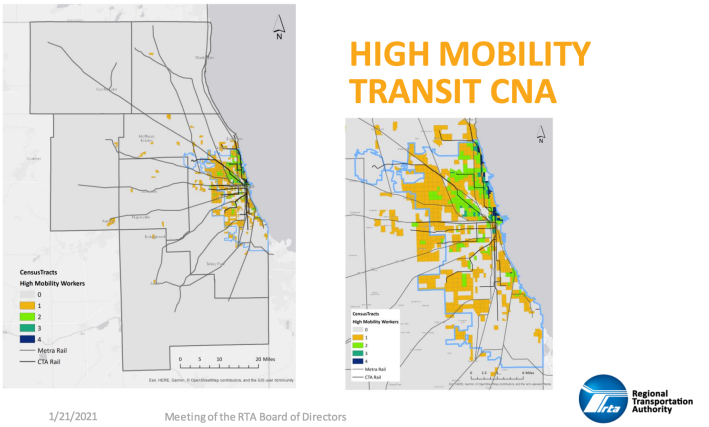

Kersten said that the federal funding will be targeted for Critical Needs Areas – areas that have a significant concentration of transit-dependent riders. The areas were determined based on three categories, dubbed "propensity transit," "equity transit" and "high-mobility industry transit." I'll explain those terms in a bit.

The RTA used the 2019 U.S. Census Bureau American Community Survey data, the most recent numbers available, as well as RTA’s own data, plus more up-to-date information from Chicago area employees to identify the census tracts.

Propensity transit includes residents who are more likely to need public transit in order to get to work. Based on RTA’s prior research, Kersten said, that includes workers age 20-44, African-American employees, workers who don’t have a car at all, and workers “making very low wage.”

While most of the population in that category was concentrated in Chicago, the map showed clusters in Joliet, Aurora, Elgin, and Waukegan; a large portion of south Cook County suburbs; majority-Black and majority-Hispanic suburbs west of the city; and a handful of smaller clusters elsewhere in the suburbs.

Equity transit includes residents who need public transportation to “access critical goods and services”: senior citizens, people of color in general, low-income households, people who use Pace paratransit, and residents with limited English proficiency. The resulting map looks similar to the propensity map, except with larger clusters in the north and northwestern suburbs, and additional small suburban clusters in every county except McHenry County.

The high-mobility industry transit category includes residents who work in fields “that are still operating or will be operating soon in person.” Kersten specifically mentioned healthcare workers, retail workers, factory workers, and teachers, as well as restaurant workers and people in the performing arts. “We know [the restaurant and entertainment] industries are hurting, more than other industries,” he said. “They may be down, employment-wise, but we're including those industries.”

The map was similar to the other two, except with fewer census tracts in south and (to the lesser extent) western suburbs, more census tracts in Skokie and Evanston, and no census tracts in Waukegan.

RTA board member Alexandra Holt, who represents Chicago, wondered whether the RTA looked at where the jobs are located, to ensure that residents would have transit options to reach them. Kersten said that they specifically weren’t trying to map where those residents worked, because they wanted to leave that part up to individual transit agencies. “We’re not focusing on service planning process. We're saying, service boards, you know your market, we trust you,” he said.

Finally, the RTA looked at how well the current services, with pandemic-related cuts and service reductions accounted for, serve each Critical Needs Area category. It found that 81 percent of the existing services serve equity CNAs, while 77 percent serve propensity CNAs and 55 percent of the existing services serve industry CNAs. The CTA accounts for the vast majority of those services, with Metra making up 16-18 percent and Pace representing 3-4 percent.

Board member Jamie Gathing, who represents suburban Cook County, which is served by some of Pace’s busiest routes, questioned those figures. “I'm wondering if population density in the city is overstating their needs,” she said. “There are essential workers who are using [Pace]. I'm just surprised that the Pace number is so low, compared to CTA and Metra.”

Kersten responded that density is indeed the biggest factor, so Pace “would perform best in those measures” in major suburban cities like Joliet, Aurora, Elgin and Waukegan. He also said that while Pace routes cover more miles than the other two transit agencies, "in total number of routes, ridership, they are smaller."

It should be noted that most of Pace service cuts involved workplace commuter routes geared toward office workers, while preserving routes serving hospitals, shopping centers, and UPS and Amazon shipping facilities.

RTA board member David Andalcio, who represents DuPage County, wondered whether COVID-19 caused any changes to the CNAs. Board member Christopher Melvin, who represents Chicago, argued that the residents within those demographics “are not that mobile,” and he didn’t expect the pandemic to change much. “Even though there are some changes, I'm not sure that some of the people captured in the equity chart are really the ones moving around,” he said.

Board member Brian Sager, who represents McHenry County, which has less transit service than the other five Chicagoland counties, said that he didn’t want to see RTA's actions hurt development in the long run. His county has transit needs, even if they aren’t obvious from the RTA data.

“The challenge, for me, is that there's a tendency for us to react very strongly to this type of data at this time, but then fail [to keep in mind] that we need to look forward as well,” Sager said. “I don't want us to take this and generalize across the board, especially when we're looking at long-term development efforts.”