By Richard Day and Conor Durkin

This piece also runs on the website A City That Works, a newsletter about public policy in the Chicago region. Richard Day and Conor Durkin edit the publication, with Day focusing on transportation issues, while Durkin concentrates on finance and budget matters. As a guest op-ed, it does not necessarily reflect Streetsblog Chicago staffers' perspectives on this issue.

Back in August, the Chicago Tribune had a nice article from A.D. Quig covering the success of the Red and Purple Line Modernization Tax Increment Financing district. The district was created in 2016 to finance improvements of the Red and Purple lines on the North Side, including renovating four stations in Uptown and Edgewater and creating the Red-Purple Bypass [aka the Belmont Flyover] to facilitate faster service.

Those projects have now come to fruition. The four stations reopened this July, and after completing the bypass in 2021 the CTA has now wrapped up rebuilding the old Red and Purple line tracks north of Belmont. As the Tribune noted, the TIF district has succeeded wildly as well, and is on pace to pay off the $625 million earmarked for the project by 2028, well ahead of schedule. That’s great! The modernization project has been a big success, and we’re glad that the TIF district was able to finance the project.

Yet the big remaining question is what the City should do with the district, which is scheduled to exist until 2052. We have a simple answer: City Council should end it.

TIFs 101

Let’s start with how TIFs work in general. They are one of Chicago’s most powerful (and least understood) economic development tools. The simplest way to think about them is as a separate economic development budget for the City, which increases property taxes citywide to generate large pools of funds available for economic development and infrastructure in specific neighborhoods. As of March 2025, the City projected that its 108 TIF districts would collect $1.15B in 2025 revenue, and end the year with $627M in uncommitted funds.

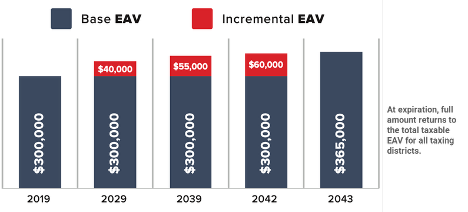

At a high level, the basic way TIF districts work is:

- Freeze the assessed property tax base within a given area for 20-30 years. That frozen tax base is what’s available for most government entities (city, county, school district, etc.) to tax

- When property values go up, whatever incremental tax revenue is collected on the increased value (relative to that frozen assessed base) are set aside and earmarked for the TIF district’s fund

- These funds are then used for funding development projects in that neighborhood

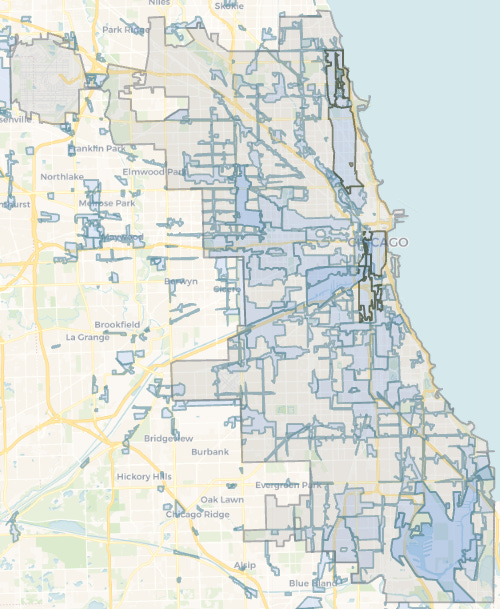

To our knowledge, no city uses TIFs more heavily than Chicago. A 2017 report from the Lincoln Institute showed that Chicago has as many TIF districts as the other nine largest cities in the United States combined. In aggregate, roughly one-third of the city of Chicago is located within at least one TIF district. The map is pretty wild:

In total, TIFs account for around 16 percent of all property taxes collected in the city of Chicago – around $1.6 billion in 2024.

That does NOT mean that other entities (the City, Chicago Public Schools, etc.) forfeit 16 percent of revenues they’d otherwise receive. Instead, those entities set a dollar value for their property tax levy. That levy gets allocated the value of all properties that aren’t captured by a TIF to determine the tax rates property owners pay. That means that with $1.6B directed to TIF districts, Chicago taxpayers end up paying $1.6 billion more in property taxes than they otherwise would.¹

Importantly, a small number of TIFs drive a large share of these property tax shifts. In 2025, 108 active TIFs are projected by the City to bring in $1.15B in revenue. Almost half of that ($486M) is accounted for by just 5 TIFs covering portions of Downtown, Fulton Market, and the North Side.

During the life of a TIF, the City can declare a TIF surplus, which sweeps dollars held in TIF accounts to their respective taxing bodies. This functions as a one-time cash sweep back to the various bodies.² At the end of a TIF district’s life (23 years, or 35 if the district is extended), the full value of the property reverts back to the standard tax rolls. When that happens, the other taxing bodies have the option to increase their property tax levies to 'capture' the increased property value that has returned to the rolls. The City also has the option to retire a TIF early (which has the same effect).

Transit TIFs

Of those 108 districts, two are special ‘Transit TIFs’ which work differently from the standard model: one created in 2016 for the Red-Purple Modernization project, and another created in 2022 for the Red Line Extension project. These were created under a separate statute and were designed specifically to finance major CTA capital projects without forcing the transit agency to take on debt.

Transit TIFs employ the same basic structure as normal TIFs. They divert the incremental property tax revenue created in a given district towards the TIF so those funds can be used for the project. For Transit TIFs, however, that diversion is pretty watered down. First, CPS actually gets their full allocation of incremental revenue -–a little over 50 percent of all funds – from the transit TIF district. After those revenues are swept out, the remaining funds are split 80-20, with the TIF getting 80 percent and other taxing districts getting 20 percent.

It gets odder still. Even though these TIFs don’t impact CPS, the property tax revenue coming from the transit TIF districts don’t count against the state mandated cap on CPS’s property tax levy – they’re just a bonus source of revenue that the district gets.

CPS’s Property Tax Cap

That cap is called the Property Tax Extension Law Limit, or PTELL. It prevents local taxing bodies from raising property taxes faster than inflation or 5 percent (whichever is lower). For our purposes, that matters for CPS – which accounts for roughly half of our property tax bills, and has been maxing out its allowed property tax hike every year in recent years.

There are some important exceptions to PTELL – including levies to pay debt and pensions, and tax revenue from newly created properties.³ But there are also two important TIF-related loopholes.

The first is TIF surpluses. Dollars routed to CPS for a TIF surplus aren’t counted against the PTELL limits. This is a large part of why TIFs tend to benefit CPS. A (non-transit) TIF doesn’t reduce the property tax levy to CPS (it just shifts it around). But a declared surplus routes additional dollars back to CPS that exceed the PTELL cap.

The second is the Transit TIFs. As mentioned above, the two transit TIFs don’t impact CPS levy collections (funds from the TIF'd properties keep going to CPS), but they are excluded from the PTELL collection. That means that the rapid growth in revenue from the RPM properties doesn’t "count" towards CPS’s PTELL limits, which allows the district to crank up tax rates on Chicagoans faster than it otherwise would.⁴

Both of these factors are substantial. An excellent report by the Civic Federation and Manuseto Institute (which explains these issues further), calculated that CPS pulled in an extra $111M in property taxes not subject to PTELL in 2023 thanks to the transit TIFs. This year, CPS’s budget includes $163 million in transit TIF revenue, making up around 3.8 percent of their total levy of $4.242 billion.⁵

The point here is not that we should defund CPS, or slash new funding sources to the bone. But taxpayers deserve some honesty from their elected officials about how much they’re paying, and where this money is going. A democratically-elected school board should have to justify a mix of tax hikes and spending cuts directly, rather than ride a backdoor escalator to higher tax rates courtesy of the RPM TIF.

Off into the Sunset

We’re talking about a lot of money. Based on the Chicago Inspector General’s dashboard on TIFs, the district has brought in nearly $80 million in the past two years (and that’s just the TIF’s share, after CPS and other entities get their cuts). This is expected to increase in coming years, with the Tribune citing estimates of nearly $100 million annually by 2031. Given that success, the district is on pace to pay off its $625 million tab for the RPM Phase One project by 2028. The question is what to do with the district after that.

Again, our answer is straightforward. The RPM TIF district was created for a specific purpose: to finance $625 million in transit improvements for the RPM Phase One. As of 2028, it will have achieved that purpose, and it should not be allowed to persist as an ongoing concern after that time.

For starters, if it left outstanding, everyone citywide will be left paying higher property taxes than they’d otherwise need to. An outstanding TIF keeps reducing the tax base available to the City, County, and other bodies, which means they’ll need to implement a higher tax rate on everyone else to reach the tax levy they want. And that $100 million per year can do a lot of good elsewhere. Based on the City’s share of the overall property tax burden⁶ for Chicago residents, we’d guess that around half of that $100 million would be released into the City’s levy, providing an extra $50 million in annual revenue to the City. That’s not a panacea to our myriad of budget woes, but it’d certainly help.

Second, it’d serve as a responsible check on the CPS property tax levy. As is usually the case with an expiring TIF, CPS would be able to institute a one-time levy increase to capture their proportional share of the property value, boosting their annual levy. But they’d no longer be able to rely on further growth on those property values to serve as a bonus PTELL-exempt levy which increases each year; their overall levy would be more subject to PTELL than it is today. Given the school board’s recent propensity to squeeze out every dollar PTELL allows them to, we think that’s a good thing. And we’re talking about potential significant amounts of money here – left unchecked, we estimate that CPS’s property tax levy could be over $450 million higher over the next decade if the RPM TIF isn’t phased out.⁷

Finally, while there are likely other capital improvement needs on this stretch of the Red Line, it’s a bad idea to dangle a large pool of money in front of the CTA. The agency has done an awful job managing other major recent capital projects, and while there have been discussions on RPM Phase Two needs, any construction is years away. There’s also no realistic prospect of federal funding in the short term.

None of this is to say that there might not be valuable projects CTA should pursue along the Red and Purple lines. It is, however, to say that CTA should have to make a new, fresh case for those projects. The City Council could even create a new RPM Phase Two TIF for them to do so (or the CTA could use some of the new capital dollars that the Northern Illinois Transit Authority now has access to). But we shouldn’t leave a larger TIF account piling up in the meantime, creating more opportunities for the city and CPS to jack up property taxes in the process.

The Bottom Line

The Red-Purple Modernization TIF has been a huge financial windfall, and it’s great that the CTA will be able to pay off this project so quickly. The City Council should congratulate them on that successful project – and then ensure that the TIF is unwound. Chicago doesn’t have a lot of fiscal flexibility, but sunsetting the RPM TIF is one of the few ways the City could improve its financial picture and reduce the pace of property tax hikes hammering Chicago residents. The alternative is an irresponsible slush fund for whatever new ideas CTA can come up with, and a loophole that lets CPS get away with hundreds of millions of dollars in extra tax increases.

1

It’s not like the parcels in TIF districts are off the hook here either – they pay the same rate as every one else, it’s just that a (growing) share of their rate is deposited into the TIF fund.

2

At present, 27 percent goes to the City, 55 percent to CPS, and the rest is distributed to other taxing bodies like the County and Forest Preserve.

3

This is a reason CPS (and the teacher’s union) should be especially supportive of new development – the full taxable value of a new office building or multifamily development flows straight into the district’s coffers!

4

It is worth noting that for a given TIF district, only one of these two loopholes can apply at a time. Because the transit TIFs aren’t impacting CPS tax collections in the first place, surplusing them doesn’t result in more dollars going back to CPS.

5

We’d also recommend Austin Berg’s recent dive into the various TIF exemptions, if you’re interested in learning more about the various loopholes.

6

Back of the envelope math: Remember that CPS is already getting their full allocation of funds from the Transit TIF, so the $100 million here would be allocated to the *other* taxing bodies. For 2023, 49 percent of all property taxes in Chicago went to CPS (so 51 percent went to the others), and 24.1 percent went to the City. 24.1 / 51.0 gets you about 47 percent going to the City.

7

This math is a bit wonky, so bear with us. We’re ballparking this based on tax revenue growth within the TIF district to date. In 2024, the RPM TIF brought in $75.6 million in tax revenue. Since we know the TIF only gets 38.4 percent of the total incremental property tax revenue in the district (80 percent of 48 percent), we can back out the total incremental revenue figure, which was around $197 million. That represents about $24.6 million in annual revenue growth ($0 to $197 million over 8 years). If we assume that same rate over the coming decade, and keep CPS’s share at 52 percent, then CPS would collect around $1.73 billion in tax revenue from the TIF district over the next ten years. If we instead assume that CPS could take a one-time levy increase for their share of this incremental revenue next year, and then keep taking an extra 2 percent (CPI) per year, they would instead collect around $1.26 billion in tax revenue from the district over the next ten years. The difference is around $467 million.

On November 12, SBC launched our 2026 fund drive to raise $50K through ad sales and donations. That will complete next year's budget, at a time when it's tough to find grant money. Big thanks to all the readers who have chipped in so far to help keep this site rolling all next year! Currently, we're at $19,702 with $30,298 to go, ideally by the end of February.

If you value our livable streets reporting and advocacy, please consider making a tax-exempt gift here. If you can afford a contribution of $100 or more, think of it as a subscription. That will help keep the site paywall-free for people on tighter budgets, as well as decision-makers. Thanks for your support!

– John Greenfield, editor