This piece also runs on the website A City That Works, a newsletter about public policy in the Chicago region. As a guest op-ed, it does not necessarily reflect Streetsblog Chicago staffers' perspectives on this issue.

Since ridership collapsed at the start of the pandemic, Chicagoland’s transit agencies have been operating deep in the red. For the last few years, federal money has filled the gap. Now that funding is expiring, and if lawmakers in Springfield don’t come up with another solution, the region faces a disaster: drastic service cuts of up to 40 percent that would wreck commutes, disrupt daily life for millions, and do serious economic damage to the region.

For years, lawmakers have rightfully insisted that any more state funding comes with structural reforms to the way transit is managed in the region. At the end of May, lawmakers introduced a revenues and reform package that cleared the State Senate, but failed to pass the House. Now conversations about transit reforms are kicking back into high gear in advance of the fall veto session.

So it seems like a good idea to revisit the governance reforms included in the new bill, which would replace today’s relatively ineffective Regional Transit Authority with a new and more powerful Northern Illinois Transit Authority.1 The reforms in the bill aren’t not perfect, and there’s much more that needs to happen in order to deliver a fiscally sound and effective transit system going forward. But they’re a strong start, and I hope lawmakers push forward with them in the fall session. Let’s dive in.

A substantially improved voting structure

To very briefly recap the challenge today, our transit system stretches across a wide range of political constituencies. A functional network requires seamless service across the region. Unfortunately, the various regions have historically fought each other for control and funding. Metra service within the city has been an afterthought (the Metra Electric Line), as has CTA service beyond the city’s limits (such as the western branch of the Blue line). And the different agencies use different fare systems and rarely integrate service. The result has been worse service, higher costs, and a whole that counts for less than the sum of its parts.

Technically, the CTA, Metra and Pace (the service boards) are all accountable to the RTA, which has the power to withhold funding and set performance requirements. But because Chicago, Cook County, and the Collar Counties all have five seats on the RTA’s board and 12 votes were required for any action, in reality the RTA’s power was limited.

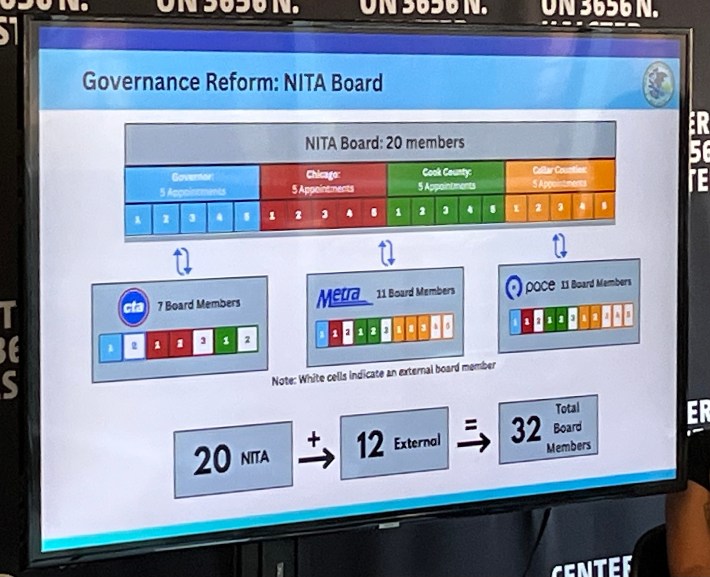

The most important change NITA makes is to reform the structure of the governing board. The new board will still include five members each from Chicago, Cook County, and the Collar Counties, but it will also include five representatives nominated by the governor – who should be more focused on the region as a whole. And one region no longer holds veto power – 15 votes are enough to proceed with major decisions (or 12 if at least two representatives from each region agree). That’s still a little unwieldy (a 12-vote threshold would be better), but it represents significant progress.

The proposed NITA and transit agency boards structure.

The board does three other things that should also help break up the fiefdoms:

- Previously, Metra, Pace and the CTA all had their own separate boards. Those boards aren’t being abolished, but a number of the NITA board members will also serve as representatives on the service boards. That should help get the service boards to be more tightly linked to the challenges in the region.

- In the past, the CTA board was dominated by mayoral appointments, and the Metra and Pace boards were run almost exclusively by the suburbs. In the new structure, the service board sizes aren’t increasing, but Chicago's mayor will get an extra appointment on the Pace and Metra boards, and Cook County will get appointments on the CTA board.

- Elected officials can no longer serve as board members. This is a particularly good change, because local elected officials (think Suburban mayors) face particular pressures to fight for their localized interests over the network as a whole. It will be especially helpful for Pace, which historically has seen a significant share of board members be local mayors who are naturally more focused on playing to individual constituencies than serving the network.2

Functional governance enables other changes

With a more functional NITA board, the newly-designed structure can also accomplish a few more things effectively. Service standards will be planned centrally, ensuring that the agencies work together to optimize transit options across the region, and enabling easier transfers from the CTA to Metra or Pace. The agencies will also be required to develop a unified fare payment system.

NITA will also be in charge of capital planning, which should help prioritize higher-quality projects that have a better chance of winning funding from Springfield or DC. And some of that capital budget might be better managed as well. The new bill creates a fast track authority for high value projects with proven cost controls, such as "itemized costs, standardized designs, or increased in-house staff to manage contracts." It also puts local governments on an expedited timeline to provide approvals or necessary right-of-way for the projects.

Importantly, this new structure keeps the transit service boards in charge of service delivery, even while NITA handles broader coordination and planning. Under the new system, the mayor will still be (mostly) accountable for the day-to-day performance of the CTA – and Chicagoans can still hold them accountable when service slips.

The bill also makes a few changes on public safety. The Cook County Sheriff is required to convene a task force to make longterm recommendations on public safety, which could theoretically lead to a systemwide police force at some point. More immediately, the agencies are required to develop a standard, app-based approach to discretely identifying emergency situations (an update that’s long overdue). The bill also creates a Transit Ambassador program, which would add additional unarmed employees to the system.

Transit oriented development

The bill also includes a provision that allows NITA to function as a developer and generate revenue from land it owns near stations. In other countries, this has been a major asset for transit agencies. It’s a nice idea, but it’s a little harder to see how impactful it’ll be in this case. NITA would still be subject to local zoning laws, and given Metra and the CTA's poor track record building new stations on schedule and budget, it’s hard to imagine they’d do a good job building apartments. There is some additional funding that NITA could use to incentivize transit-oriented development, which might help a bit.

Recognizing that one of the best ways to boost transit is to boost density around transit, the bill also makes some land use changes. The most important of these is to eliminate mandatory parking minimums within a half mile of rail hubs, and one-eighth of a mile of high-frequency bus corridors. That doesn’t prohibit developments from adding parking, but by not requiring more parking than is necessary, the legislation will make it easier (and cheaper) to add housing or commercial space in areas with high quality transit. Chicago has already done this, but this change could make a real difference in the suburbs.

Farebox recovery ratio

Finally, the bill changes the current farebox recovery ratio, which (theoretically) requires the RTA to cover 50 percent of its expenses via operating revenue. That wasn’t really happening even before the pandemic – a series of exceptions and carveouts had allowed the agencies to operate at closer to 40 percent cost recovery. That’s plummeted to roughly 25 percent in recent years, which is where the new level would be set.

I understand why this needs to happen now – a 50 percent requirement is obviously untenable in the short run. But the goal should be to drive the number back up over time. A low farebox recovery ratio is a sign of weakness – transit should be well-run enough to compete with other modes of transportation. And longer term, a higher recovery ratio is a tool for accountability: it forces transit agencies to deliver service that riders actually value, and it provides a constraint to push back against demands for ever more spending. Notably, the best-run transit systems in the world have recovery ratios of 70 percent or higher.

CTA, Metra and Pace need a better governance structure, but they also need to do a better job running their day-to-day operations. The CTA still hasn’t made much progress on its safety issues, Metra is trying to build new stations for $80M a pop, and even as the revenues have collapsed, the service boards have carried on with business as usual rather than taking the opportunity to make hard decisions to improve efficiency and cut costs. 3

Now the transit agencies are asking for an additional $771M just to maintain current operations – and up to $1.5B to deliver better service. It’s understandable that voters (and lawmakers) are hesitant to shell out so much money to organizations that have done a less-than-stellar job with the resources that they have today.

We can’t go over the cliff. But I’d much rather keep the pressure on a newly constituted Northern Illinois Transit Agency to continue to improve, rather than writing the biggest possible check in the short term. It’d be great to route an additional $1.5B flow into a high performing, integrated regional transit system – but if we write that check today, I worry that it’s less likely that we get to that outcome.

Of course, we also can’t afford to crush the system we have in the meantime. But that’s a case to get to $771M now, and then map out a path to more as the system continues to improve. From a funding perspective, that’s a much easier hill to climb. With $200M in interest from the road fund and another $100M from tollway surcharges, plus an additional $150M better-performing sales tax revenue, there’s an opportunity to preserve the system we have with relatively moderate tax hikes today, and then map out a path to more revenue as ridership and service quality improve.

A step in the right direction

The good news is that the reforms embedded in the May bill represent a pretty significant step in the right direction. They’re not exactly what I’d put on paper, but they represent a pretty solid compromise that delivers a governance structure that our region desperately needs.

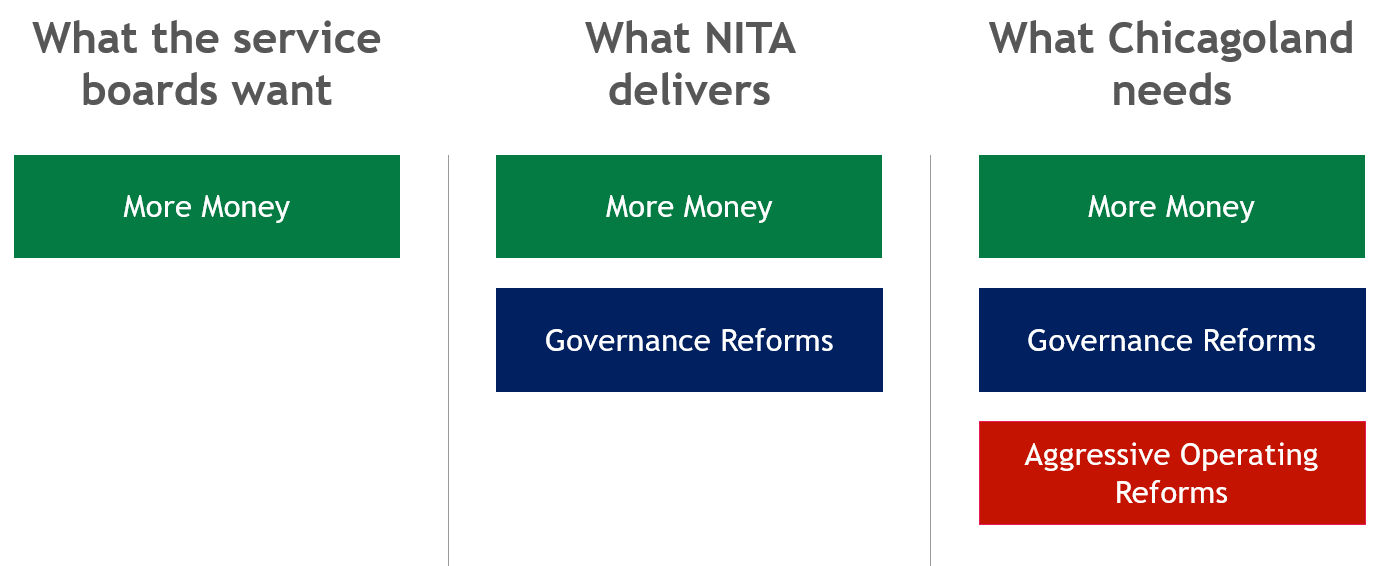

The less-good news is that the reforms included in NITA are not, on their own, enough to rescue the system. As I’ve written before, a functional transit system will require not just more money and reforms to board composition, but also major improvements in the way transit service is managed and delivered. Springfield needs to make sure transit riders in Northern Illinois see changes at all three levels.

1 If you’re following along at home, I highly recommend the Metropolitan Planning Council’s comprehensive summary of the major provisions, which also notates the specific page they can be found on.

2 This may also explain some of the current opposition to the reforms from suburban Mayors. As friend of the newsletter Star:Line Chicago notes, four of the mayors who have signed a letter of opposition to the NITA reforms would lose their Metra or Pace board seats.

3 To just throw out one example, this would be a perfect opportunity to consolidate bus stops – a reform that would generate some complaints, but make a real difference in service quality and cost. But the CTA hasn’t even really floated the idea. And it’s not like other transit agencies aren’t making progress here - last year Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority cut costs by $120M, while redesigning parts of its bus network and re-introducing automatic train operations.

Do you appreciate Streetsblog Chicago's paywall-free sustainable transportation reporting and advocacy? We officially ended our 2024-25 fund drive in July, but we still need another $43K+ to keep the (bike) lights on in 2026. We'd appreciate any leads on potential major donors or grants. And if you haven't already, please consider making a tax-deductible donation to help us continue publishing next year. Thanks!