This piece also runs on the website A City That Works, a newsletter about public policy in the Chicago region.

The transit bill that cleared the House and Senate in Springfield last week is a monumental achievement. At the 11th hour of the veto session, 4 a.m. to be exact, legislators passed a bill that saves transit in Chicagoland from backbreaking cuts. It also has the potential to transform our system for the long run. The legislation does this in two ways.

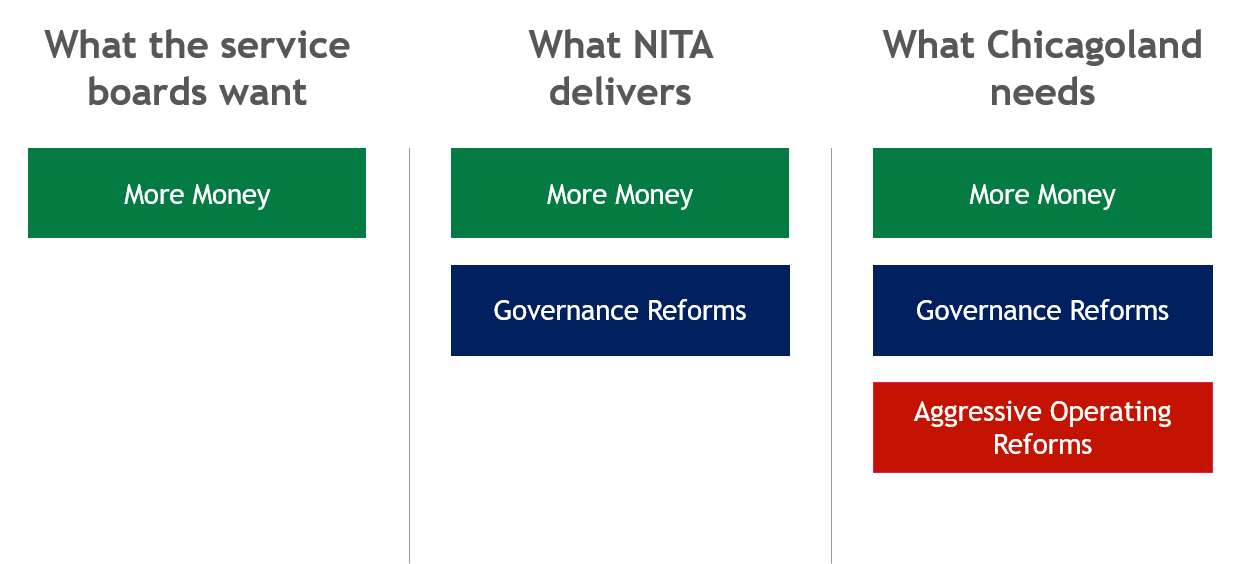

First, it implements several major reforms to the way transit is managed. I've previously discussed this, but the short version is that the new Northern Illinois Transit Agency will have the power to oversee a unified transit network that makes Metra, Pace, and the CTA work together more effectively for the benefit of city residents and suburbanites alike. It also enables better central oversight and management of core functions like service planning, capital budgets, and safety.

Second, the bill provides $1.5 billion in annual funding to both address a looming fiscal cliff (currently about $230 million and estimated at $700 to $800 million in coming years ) and improve service. It also does so with a healthy degree of fiscal sense. The majority of the funding comes from redirecting the state’s existing motor fuel tax to transit (providing about $860 million), dedicating interest on the state’s Road Fund to transit (roughly $200M in revenue) and permitting a 0.25 percent increase to the Regional Transportation Authority's local sales tax. I don’t love that last piece, but it’s a much better approach than many of the other ideas floated.1

Is the 0.25% RTA sales tax increase to fund transit "regressive"? It's not ideal, but paying an extra quarter for a $100 purchase should not be a major hardship.It's certainly less regressive than transit cuts that would have forced people to drive.@rtachicago.bsky.social @atalliance.bsky.social

— Streetsblog Chicago (@chi.streetsblog.org) 2025-11-03T18:59:01.351Z

Getting here was hard. It required fighting through generations of city-suburb political animosity in the middle of a brutal budget environment. That success is a testament to the unprecedented coalition of labor, business, environmentalists, and transit advocates who pushed to get this bill over the line. Everyone who fought for this – from the team that wrote the initial Plan of Action for Regional Transit report back in 2023 to the advocates who showed up last week to lobby legislators in a train costume – should be proud of this bill.

The challenge ahead

But it’s far too early to declare victory. On its own, more funding averts short-term disaster, but does nothing to solve our longer term transit issues. And while the governance reforms could lead to better service, there’s no guarantee of that. If we leave the same sorts of decision-makers in charge, with the same institutional memory, we could end up with little more than a cleaner organizational chart for a still-dysfunctional system.

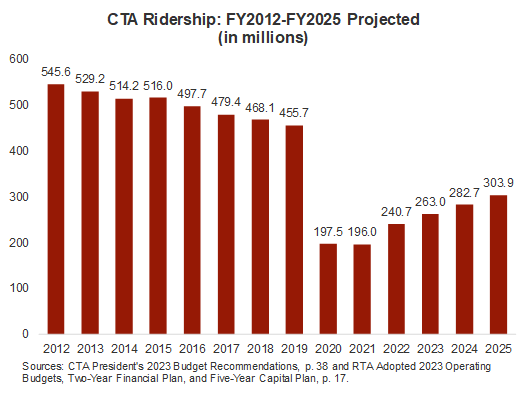

Source: Civic Federation

CTA ridership had already dropped 16 percent in the seven years before the COVID-19 pandemic hit. Key pieces of the system have been left to rot. More than 30 percent of the rail system is now covered by 'slow zones' thanks to deteriorating track conditions. And leaders of the various agencies (but especially the CTA), had displayed a shameful lack of focus on basically anything other than asking for more money. The result is a slow-moving crisis that, absent radical reforms, will continue to drag down our region – funding or not.

Better operations

These problems break into two categories. First is the operations of the system we have today. The transit agencies urgently need to deliver better service with the resources that they have. Crucially, that can’t just be measured by running more trains and buses – it needs to be measured by whether the agencies can deliver service that riders actually want to use. That means keeping tight control over operating costs, even with more money to spread around in the short term.

One of the better ways to measure this is by looking at the farebox recovery ratio of the system – or the share of operating costs that are covered by riders actually paying to ride the system. A higher recovery ratio indicates the system is doing a better job serving riders and controlling costs. A lower ratio indicates that the system is functioning more as a system of last resort for those with no other options, and a jobs program for employees.

Unfortunately, the RTA’s farebox recovery ratio was headed in the wrong direction pre-pandemic, and it’s cratered since. While the RTA used to be required to maintain a 50 percent recovery ratio (which was actually lower once accounting for a series of exemptions), the new NITA legislation drops that level to 25 percent.2

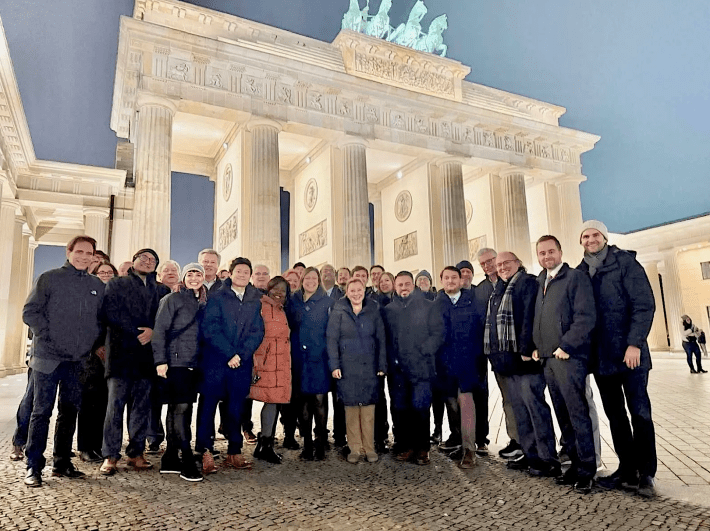

The common rejoinder is that the recovery ratio is a straightjacket which has prevented agencies from experimenting or cooperating with each other. But well-run transit agencies in other countries deliver far higher recovery ratios – including Berlin, a city showcased as one of the examples legislators toured as a model for NITA.3 They’ve also recovered far better than the RTA has. The pitch to taxpayers and legislators was that funding and reforms could deliver a world class transit system. Well, the money showed up. Now it’s time to deliver on that promise.

There are a lot of steps that we’ll need to take to bump the farebox ratio up. Management will need to manage future labor contracts effectively, and ensure new service is aimed at areas with high growth potential. It will also require making operational reforms that boost ridership as a whole, even if they require stepping on a few toes. As I’ve noted before, a firmer crackdown on disorder and violence is sure to upset some on the far left, but it’s critical for getting more people to return to the system.

[As a guest op-ed, the opinions stated in this piece do not necessarily reflect Streetsblog Chicago staffers' perspectives on this issue. SBC contributor Austin Busch's summary of the transit bill includes a full rundown of the enforcement and safety measures included in the legislation.]

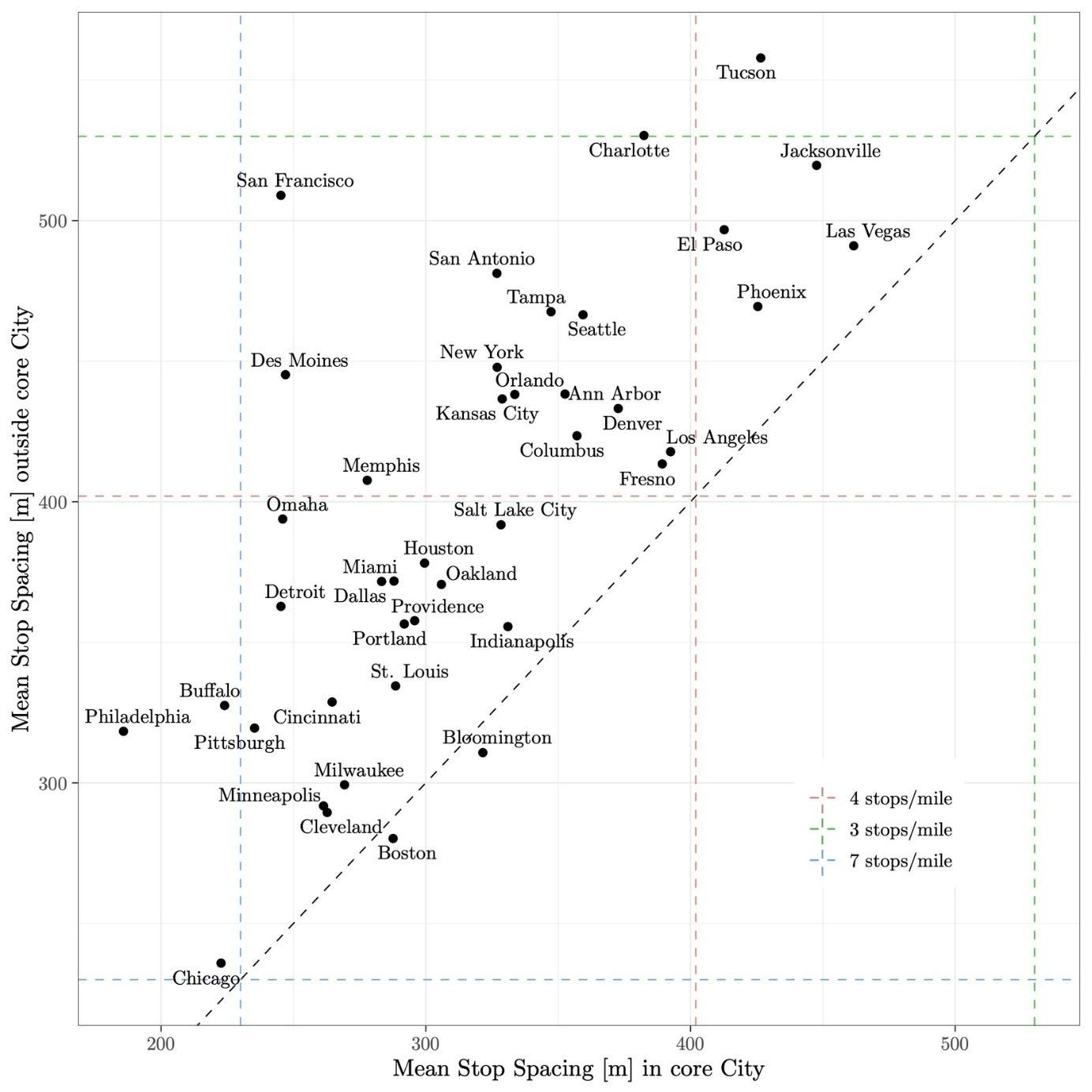

Another example is the CTA’s spacing of bus stops. Today, bus stops are comically close together – often at almost every block, in violation of transit best practices, and far more densely spaced than other US cities. Transit agencies consistently describe bus stop consolidation as the most successful action they can take to speed up bus service, which reduces costs (because it takes fewer operator hours to run a route), and improves travel times.

Source: Pandey et al, 2021

The downside, of course, is that the CTA might get yelled at by a few riders who lost the stop outside their front door. But if we want to start acting like a world-class transit agency, that’s a trade-off worth making.

Controls on capital costs

While improving day-to-day operations requires grinding out a series of efficiencies, the way we approach capital projects requires a full teardown. Here are a few examples:

- Metra is about to spend $74 million to replace an existing open-air station in Hyde Park.

- The CTA wants to spend $440 million dollars to replace the existing station at State and Lake with a “gateway to downtown.” Remarkably, for that price tag, we’ll somehow get no actual improvement in service beyond ADA accessibility.

- Of course, the Red Line Extension, now set to cost $5.75 billion, will be the most expensive transit project per mile ever built in North America.

The cost of these projects is borne by taxpayers. They also mean that other projects never get off the drawing board. Bus rapid transit is no closer to fruition now than when Rahm proposed an Ashland BRT line back in 2013. Much worse, the CTA can’t find money to make critical repairs to the Forest Park Branch of the Blue line. As the system rots, expanding slow zones mean that that branch has had the worst post-Covid ridership recovery of any line.

For a long time, the dodge here was that the feds were picking up a large share of the cost. That excuse was never all that compelling, but it’s also much less true now than it used to be. Given the exploding costs of the Red Line Extension, roughly a quarter of the price tag is being picked up by Washington – if that money ever ends up coming at all. And the new transit bill includes $180 million of annual funding exclusively dedicated to the region’s capital spending (via the road fund interest). Those are fundamentally flexible dollars coming straight out of the pockets of state and local taxpayers.

We simply cannot afford to throw that money down a rathole of unnecessary alternatives analyses and overbuilt stations. We need to drastically curtail the design ambition and revisit cost estimates for the projects listed above – and be willing to walk away if necessary, rather than put the system in greater risk. CTA and Metra also urgently need to adopt international best practices for transit cost management, bring more design work in-house, and hire transit professionals from systems in other countries that have a track record of building at reasonable cost.

This is the really hard part

It may feel harsh to focus on these challenges so quickly after a big win. But the urgency of the fiscal cliff was central to driving the hard political choices we needed to make. In many ways, the system is at its most peril now – after the fiscal cliff has been averted. With the pressure now off, it will be easy to sink back into old, bad habits. And if this opportunity is wasted, legislators in Springfield will be much less forgiving in the future.

This is the last, best chance we have to deliver the sort of transformative transit system the region deserves. We can’t afford to waste it.

Richard S. Day writes about public policy at A City That Works, and has freelanced for Streetsblog Chicago for the last five years. Richard previously worked in the Mayor's Office during the Lori Lightfoot administration.

1

Note – there are a few other really good reforms in the bill, including a statewide elimination of parking mandates near transit. Check out Austin Busch has a great comprehensive rundown of the details.

2

Historically, the CTA has had the highest farebox recovery ratio of the three service boards. Density really is a crucial ingredient to effective transit.

3

These are just European cities. Many Asian cities have farebox recovery ratios upwards of 100 percent.

Do you appreciate Streetsblog Chicago's paywall-free sustainable transportation reporting and advocacy? We officially ended our 2024-25 fund drive in July, but we still need another $42K+ to keep the (bike) lights on in 2026. We'd appreciate any leads on potential major donors or grants. And if you haven't already this year, please consider making a tax-deductible donation to help us continue publishing next year. Thank you!