By Daniel Koslovsky

As the $771 million total northeast Illinois transit fiscal cliff looms, public transportation agencies and advocates are calling for $1.5 billion in additional yearly state funding to upgrade the public transportation system. The discourse over fully funding local transit is based on the assumption that it’s worth the money to do so.

That belief is strongly supported by hard data. In the fall of 2024, the report "Impact of Transit on Mobility, Equity, and Economy in the Chicago Metropolitan Region," by researchers from Argonne National Laboratory and MIT, found that or every $1 invested in the CTA, Metra, and Pace, Chicagoland benefits from $13 in economic output.

As a frequent CTA and Metra rider, and a Masters of Public Policy candidate at the University of Chicago's Harris School, I was was interested in taking a close look at that subject myself. So I put on my policy analyst hat to put together a quick cost-benefit analysis of the proposed transit investment.

Before jumping into the analysis, I want to quickly acknowledge that I am personally and ideologically interested in seeing local transit become fully-funded. To guard against that bias, I tried to err on the side of being extremely conservative when calculating benefits of transit funding. Now let’s do some math!

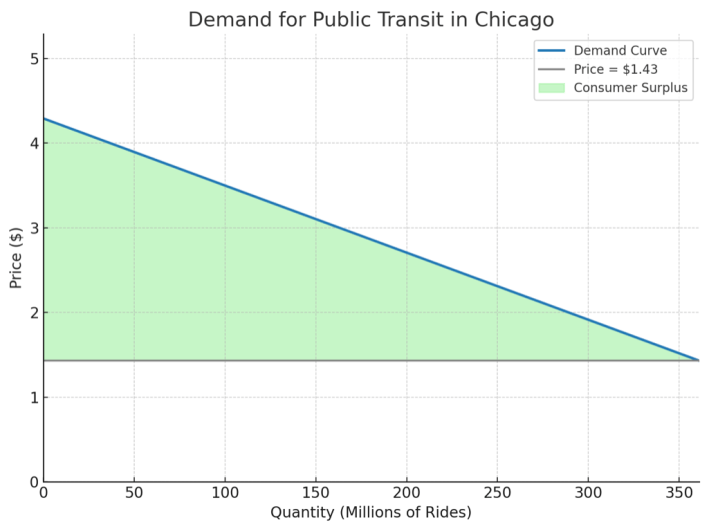

To start, we can model the market for public transportation in the Chicago area using the number of trips and amount of farebox revenue stated in the Regional Transportation Authorites 2024 annual report. According to the recommendations of the Victoria Transport Policy Institute, every 1 percent of service reduction will result in a 0.5 percent loss of ridership. So factoring in an "elasticity of demand" of -0.5 percent gives us the following diagram:

The shaded area represents consumer surplus: the amount of private value consumers get from riding transit left over after they pay the fare. In this case, the answer is $516 million. I want to emphasize the word "private" in private value here because, as we’ll see, most of the value of public transit comes from its social benefits.

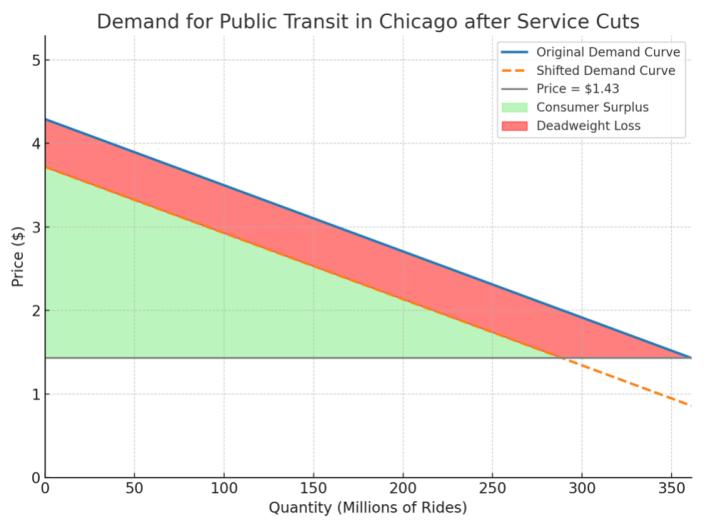

Now let’s look at the service at stake with the fiscal cliff. First, we need to measure how much ridership would drop if decision-makers fail to plug next year's $771 million hole, which would result in a projected 40 percent service cut. So using VTPI's ridership elasticity figure, the reduction in service will lead to a 20 percent loss ridership. For CTA, Metra, and Pace, this translates to 72 million fewer rides a year or 289 million total trips.

We can use that number to model the demand after the service cuts. In the chart below, the red area represents the value to the public that would be lost from service reductions. Those are people who would have chosen to ride transit at its current service levels, but would no longer want to, or would be unable to, use the system after the 40 percent cuts. The size of the red area, the deadweight loss from the cuts, is equal to $186 million.

The calculations so far only take into account the private benefit of individuals riding public transit. But private benefits are only part of the picture. The largest gains come from the social benefits that extend beyond the riders themselves.

First, increased use of public transportation improves the physical health of a city's residents. Unless you live right next to a transit stop, you’re going to end up walking, biking etc. for a portion of your trip on transit.

The cumulative health effect of this extra physical activity adds up. According to VTPI, the monetary cost from reduced physical activity of going from a good transit system to one on par with the average North American city (read: bad) is $90.57 per capita in 2025 dollars. That’s exactly what is threatening to happen to Chicago if the fiscal cliff isn’t averted. Using the population of Chicago proper, about 2.7 million, that works out to a lost benefit of $241 million.

In addition to increased physical activity, public transportation makes it easier to access healthcare. This makes it less likely people will put off preventative, early stage, or chronic care that saves them money on more expensive care later and reduces everyone else’s insurance premiums. The value of this is huge – a National Center for Transit Research study estimated the cost of a foregone medical visit to be $970 per round trip.

That report found the resulting benefit-cost ratio for public transportation on just its impact on access to healthcare was found to be 0.86 for small urban areas. It’s likely higher for Chicago, as the benefits of public transportation tend to increase according to population density, but I’ll use 0.86 to be safe. This implies that the cost of lost medical trips from losing $771 million worth of service would be $662 million.

Beyond providing its own positive externalities, public transportation removes the negative externalities from car use by reducing the number of car trips. We can use VTPI’s guidance on the cost of vehicle use per vehicle mile traveled across a wide range of categories to quantify this for the following categories (cost per vehicle mile in parentheses):

- Crashes ($0.08525)

- Parking ($0.2937)

- Congestion ($0.06193)

- Road facilities ($0.0403)

- Land value ($0.0527)

- Traffic services ($0.02325)

- Air pollution ($0.085715)

- Greenhouse gas emissions ($0.235011)

- Noise ($0.02015)

- Resource consumption ($0.065069)

- Barrier effect ($0.027342)

- Land use impacts ($0.12865)

- Water Pollution ($0.0217)

- Waste ($0.00062)

In total, the cost of externalities per vehicle mile driven by a car is $1.14.

To apply these recommendations, we need to find the additional miles that would be driven as a result of 40 percent service cuts. Based on data from Moovit Insights 2022 Global Transit Report, the average miles traveled per ride for Chicago transit was 5.87 miles. Thus, a reduction in 72 million rides would result in 421 million miles lost in public transit travel.

How many of those lost trips will now be traveled by car? The best estimates that I could find suggest that the number is somewhere between 30 percent and 60 percent. If 30 percent of the lost transit rides become car trips instead, then an extra 126 million car miles would be driven in Chicago in 2026, assuming that drivers and public transportation riders travel the same distance for the same trip.

However, transit trips are typically shorter because they involve walking or biking part of the way, or, in the case of rail, can use a more direct route. One study estimated that the ratio of car miles traveled to transit miles traveled for the same trip is 1.43. Multiplying 126 million miles by 1.43 we get 181 million miles. At a cost of $1.14/mile, that means increased car use would cost the public $206 million.

Shrewd readers with some training in economics might object to my using $771 million as the benchmark of the benefits needed to outweigh the costs. After all, the State of Illinois does not have $771 million simply lying around, so any funding will have to be raised through new taxes, surcharges, and/or fees. If those new expenses are placed on competitive markets without distortions from externalities, then they will create deadweight loss that needs to be added to the costs.

Although, there is a lot of uncertainty surrounding the source of revenue for a transit funding bill, we can analyze HB 3438, the version of the bill that passed the Senate last May, but didn’t receive a vote in the House. It proposed to primarily raise revenue through a 10 percent surcharge for ride-hail trips, and a $1.50 "climate impact fee" surcharge on retail and restaurant deliveries made using a motor vehicle. Streetsblog has nicknamed the latter "the burrito taxi tax."

Let’s look at the market for rideshares first. A recent University of Chicago study found that the price of ride-hail trips in Los Angeles was $2.56/mile. The cost of living is about 30 percent higher in LA than Illinois, so I’m going to deflate that number to $1.97/mile to adjust for the cost-of-living difference. Thus, a 10 percent fee for ride-hail trips would come out to $0.197/mile.

However, we know that there are significant negative externalities in this market because Uber and Lyft drivers use motor vehicles to transport customers. Driving your own car incurs $1.14/mile in social cost. But the externality is actually greater for drivers of ride-hail vehicles because about 45 percent of the miles they drive are either waiting for a ride request or driving to pick up a passenger. Hence, the social cost incurred for every passenger mile driven by a ride-hail driver is actually $2.07/mile. This dwarfs the cost of the proposed 10 percent fee, meaning that there is no deadweight loss incurred and that the ride-hail surcharge actually makes Illinois better off as a policy unto itself.

The story in the retail and food delivery market is the same. The proposed $1.50 surcharge is the equivalent of the negative externalities created by a motor vehicle delivery of 1.32 miles. But, outside of the densest parts of Chicago, it’s unlikely that any DoorDash driver is averaging that short a distance per delivery in Illinois. Anecdotal evidence also suggests that the average number of miles driven per delivery in this state is much larger, likely in the range of 3 to 8 miles depending on where a driver is located. Thus, just like the ride-hail fee, the burrito taxi tax would be good policy, even before the money is used to fund transit.

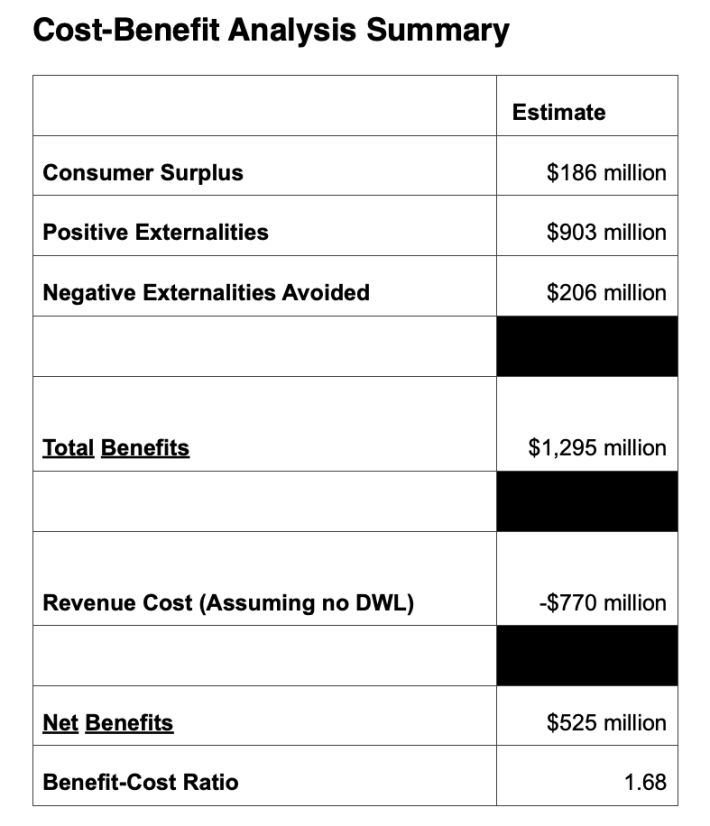

Public policy almost always requires some sort of tradeoff to make progress. Having a sober view of those tradeoffs, instead of burying your head in the sand and insisting that you can have your cake and eat it too, is a necessary trait for good policymaking and leadership. Occasionally, there will be times for when it’s an easy decision because the benefits of a policy are so overwhelming. As the table above makes clear, this is one of those times! In this extremely conservative estimate, benefits are almost 70 percent greater than the $771 million cost.

I reached this conclusion despite the fact that I left out several other factors that would boost the value of funding Chicagoland transit because they would have been too difficult to quantify. I'll quickly name a few. Improved service from the reforms being proposed as part of a funding package, transit’s economic multiplier effect, and internalities from the extra cost of using a car instead of transit would all provide major additional benefits.

We shouldn’t be surprised by these results. Public transportation projects regularly pencil out in cost-benefit analyses, and do so especially easily in large metropolitan areas.

The slam dunk nature of this policy makes the failure of Illinois lawmakers to pass a transit funding and reform bill by the end of the spring legislative session all the more frustrating and disheartening. Luckily, there’s still time to avert disaster. Here’s hoping that Springfield takes the easy policy win sitting there waiting for them.

Do you appreciate Streetsblog Chicago's paywall-free sustainable transportation reporting and advocacy? We officially ended our 2024-25 fund drive last month, but we still need another $44K to keep the (bike) lights on in 2026. We'd appreciate any leads on potential major donors or grants. And if you haven't already, please consider making a tax-deductible donation to help us continue publishing next year. Thanks!