Read Part 1: "Can automated enforcement, 25 mph speed limit be done equitably?" here.

As I discussed yesterday, José Manuel Almanza, Director of Advocacy & Movement Building for the local mobility justice nonprofit Equiticity, recently had a long conversation with me about efforts to prevent Chicago crash fatalities. Read the intro to the previous post for background on what inspired this discussion.

Yesterday's post shared the first part of our conversation, discussing speed cameras, and recent efforts to pass a default 25 mph speed limit. I floated ideas to make traffic enforcement and the lower speed limit more equitable. These included income-based traffic fines, and restoring the ticketing threshold from 6 mph back to 11 mph, along with lowering the speed limit. Read Wednesday's post for more details.

Almanza was generally supportive of my proposals. But he said, "If all we're doing is making it more affordable to folks to pay these fines, if it's just that by itself, then no, it's just not enough... The real equity comes in when, yes, you will get fined for going over the speed limit, or running the stop sign, or something like that, of course. However, we're gonna do everything we can to make sure that the environment around us does not promote or does not condone people doing these things, and actually makes it very difficult."

However, getting approval from residents and alderpersons for street redesigns that discourage dangerous driving and prioritize walking, biking, and transit use is easier said than done. That's especially true in part of town with subpar transit access, long distances between destinations, and other factors that cause people who own cars to drive more often. That includes communities of color on Chicago's South and West sides that have the highest crash fatality rates.

So in this part of the conversation, we also talked about strategies to convince locals that projects such as road diets, pedestrian improvements, bus-only lanes, and protected bike lanes, will be beneficial for them and their neighbors.

John Greenfield: Studies have shown that road diets help reduce speeding. Things like sidewalk extensions, raised crosswalks, speed humps on side streets. The City of Chicago doesn't really do speed humps on main streets. And other infrastructure changes, like you were saying earlier, those can help reduce serious and fatal crashes.

I think a really good path forward is kind of... I'm sure you guys have worked a little bit with the Southwest Collective [a group working to improve sustainable transportation in the Midway Airport area], correct?

José Manuel Almanza: We have.

JG: They've done a lot of advocacy, along with the Active Transportation Alliance, on trying to make Pulaski Road safer. That's a street where there were a couple of pedestrian fatalities in the last year on the South Side, and some motorist fatalities as well. It seems like that's a good example of trying to get buy-in from the community for making infrastructure improvements on a deadly major street.

Can you tell me more about what's going on with that on the South and West sides, in terms of trying to get more local support for infrastructure changes that will reduce serious and fatal crashes. Have you folks been involved with that?

JMA: We have. And I use it pretty frequently, and I noticed the new improvements the City added recently, where they added those yellow cones to prevent people from driving on the median for example, and they added a few bump outs.

Friends and family members know this is my line of work and brought it up. And we're talking about how it's good that we're seeing these things. However, some time later, we're seeing some of those posts that are knocked down because a driver went over them, or we're seeing the burnout marks from cars that are doing donuts, for example, on a wide intersection. So we're still seeing signs that it's not enough.

One of the things that we're working on right now is doing a public engagement project, trying to talk to community members around bus rapid transit, and Pulaski Road is one of the corridors that the City of Chicago is considering starting a pilot program on.

And so when we're talking to people around Pulaski here in the West Side and some of the South Side, and we're talking to them about this idea of what would this BRT pilot program look like. And as soon as I mentioned that that it's kind of like the 'L', but for a bus on the road, their eyes get wide because they know the benefits on the 'L'. Now they see it here on the road, and when we're talking about Pulaski on the Southwest Side, specifically where it's about a four-lane, plus the median, so it's maybe like five and a half, six lanes wide lane, they imagine that BRT lane right down the middle.

And then with that comes more pedestrian infrastructure, more cycling infrastructure. It makes it more dense, so that drivers don't feel like, "Oh, this is a wide open space, and I can just speed down this corridor. They see that. And then to tie it all together, I bring it back to creating safety. Like, this is one way where we can create a safer roads for people who are trying to cross Pulaski to get from one side another, or maybe get to the bus. It'll make it safer for them. It'll make it safer to get to the bus riding your bicycle. And it'll even make it safer and better for for drivers, because there will be fewer people on the road driving, and more people using BRT.

All that to say that the way we are talking to community members, specifically around Pulaski, making the road safer, is through the lens of bringing the resource of bus rapid transit into our community.

JG: Okay, interesting. The issue with a lot of making physical changes to improve safety is that if you propose things that might make it a little harder to drive fast, or converts some of the lanes for drivers, there could be a lot of pushback. You know, people thinking that's not fair to drivers.

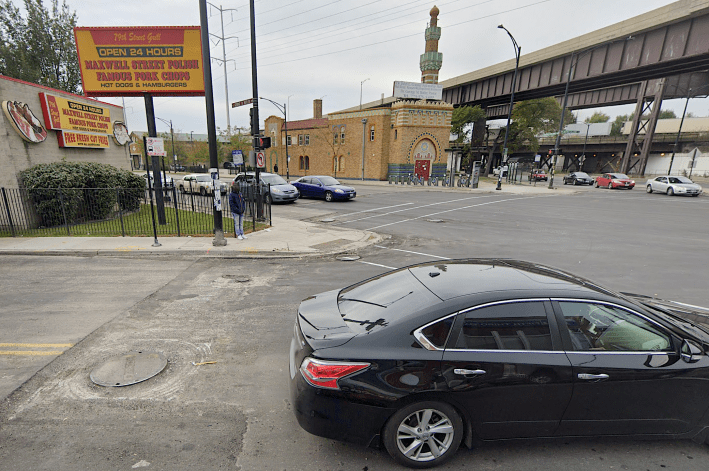

That has played into the traffic safety issue. A really good example that was on Stoney Island Avenue. So as you know, that's an eight-lane road surface road on the South Side, and the Chicago Department of Transportation proposed converting two of the car lanes to protected bike lanes. The local alders were really opposed to that. They basically squelched the plan because they said it would create traffic jams during rush hours.

And not long after that, two African American men were killed by speeding drivers on that portion of Western. Those were tragedies that might have been prevented by a better street design.

The real takeaway is that a lot of a lot of the alders are opposed to things that they think would make life less convenient for drivers, including in predominantly African-American neighborhoods that are seeing so many crash fatalities. A lot of the City Council members in those parts of town voted against the 25 mile per speed limit.

So that's the $10,000 question if we want to do things like road diets, BRT, and a safer speed limit: How do we get more grassroots support for this stuff, which turns into more aldermanic support for these things. What role does Equiticity play in that?

SMA: That's a great question. And that intersection at 79th, and Stony Island, and South Chicago, is an intersection that we have been trying to, along with CDOT, reimagine that intersection, but similarly faced, not just pushback, but there's never enough funding to go around.

Big picture, one of the things is that we're not going to make everyone happy, especially when it comes to civic service, public services, politics in general, government in general. So I think that puts the burden on us, the advocates, the organizers, to organize our communities and make it so that City Council members or just legislators in general, they have to listen to us, because we are the majority. We are the ones who need the service and who pay our taxes to get the service. So we deserve it, and we should demand better. So that's on us to organize our communities to make this happen.

That being said, like I mentioned at the beginning of our conversation, alders will vote against something, but then also are against the alternatives of the other solutions that will help address that problem. And again, that comes back to us, we have to be better at making a point to community members and to City Council members to go this route. The status quo has catered to the drivers for a long time, but times are changing, and we have to be the ones to be the forefront of that change.

Read Part 1: "Can automated enforcement, 25 mph speed limit be done equitably?" here.

Did you appreciate this post? Streetsblog Chicago is currently fundraising to help cover our 2025-26 budget. If you appreciate our reporting and advocacy on local sustainable transportation issues, please consider making a tax-deductible donation here. Thank you.