When public transportation professionals, and representatives of various transit-related industries, gathered for the annual Transport Chicago conference last Friday, the Chicagoland transit funding cliff was literally at the top of the agenda.

The "Funding Strategies for Regional Transit as Fiscal Cliff Approaches" session wasn’t the only seminar held that morning, but the organizers put it in the largest conference space and it was the best-attended of the early morning sessions. For those who might have missed it, the CTA, Metra and Pace have struggled to regain pre-pandemic ridership, which has hurt fare box revenue. While the agencies have used federal COVID-19-related stimulus funding to fill the gaps, that money is currently expected to run out by 2026. The Regional Transportation Authority puts the estimated shortfall at $730 million.

During the panel, transit experts discussed the funding issues Chicago area transit agencies faced before the pandemic, the challenges of regaining ridership, the impact of the funding cuts and potential solutions. Panelist Thomas Bamonte, senior Advisor at the Metropolitan Planning Council, pitched a particularly bold proposal: congestion pricing.

Defining the Challenges

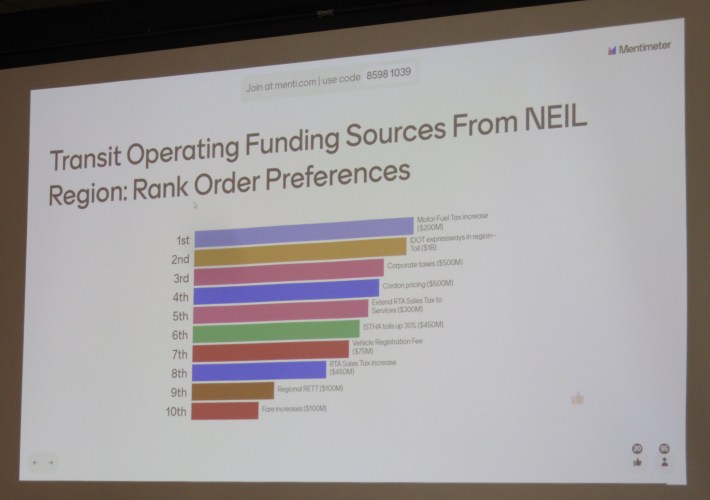

Panelist Maulik Vaishnav, senior deputy executive director of planning & capital programming at the Regional Transportation Authority, put the fiscal cliff in context, discussing challenges Chicagoland transit faced even before COVID. With federal funding only covering a small portion of day-to-day operations, the local agencies had to rely on fares, advertising, rental revenue, and state and RTA funding sources.

All three transit systems get funding through the RTA sales tax, which is higher in Cook County (1.25 percent) than in the collar countries (.5 percent). The CTA gets additional funding from Chicago's Real Estate Transfer Tax. State funding for day-to-day operations is set at 30 percent of RTA sales tax revenue and 30 percent of the Real Estate Transfer Tax revenue. That means that it goes up and down depending on how much those taxes bring in on a given year.

Vaishnav said the fact all three agencies are legally required to get at least half of their revenues through fares doesn’t help matters. "In the past, we've been operating with deficient funding consistently, and COVID just exacerbated those things." He warned that, if the fiscal cliff isn’t addressed, the agencies may need to cut as much as 20 to 30 percent of service in 2026.

Panelist Kate Lowe, an associate professor at the University of Illinois Chicago’s College of Urban Planning and Planning Affairs, said the cuts would lead to a "vicious cycle," aka a transit death spiral. "Lower fare revenues risk cuts, [which means] riders will leave transit, cancel trips, that will lead to lower revenues, which lead to cuts," she said.

Vaishnav also noted that even if the Illinois General Assembly hypothetically raised the RTA tax and/or changed the way the funds are split, it could take as long as six months before any of that money ends up in the RTA’s coffers. "We don’t have that much time to [take care] of the fiscal cliff," Vaishnav said.

The disparate impact

Lowe said that, as transit agencies look to recapture riders, it's important to bear in mind that "there are huge time burdens to using transit." An average commute by bus in CHicago, she said, is 47 minutes, versus 26 minutes by car. She noted that this is notable since bus passengers account for a larger portion of CTA ridership than 'L' customers.

Not by much, though. According to CTA ridership reports, as of March 2024, bus riders accounted for 59.41 percent of CTA ridership, while the ‘L’ passengers made up 40.59 percent. However, there is a caveat to these numbers. CTA ridership reports don't track how many riders transferred between the two modes).

Another burden, Lowe said, is the transit inequities between majority-white and majority-POC neighborhoods. Black and Latino communities are more likely to have transit-dependent riders, and are more likely to have less frequent service, fewer express options and less service coverage. Black Chicagoans, Lowe said, tend to spend more time traveling by transit than white residents, even when the distance is the same.

Lowe pointed to the recent study by Argonne National Laboratory and MIT on how transit loss would impact the Chicago region. The report, which was commissioned by the CTA and released earlier this month, estimated that "Without public transit, over two million activities would be canceled daily, resulting in an estimated $35 billion annual loss in direct economic activity. This estimate includes lost jobs, closed businesses and increased living costs."

One thing to keep in mind, Lowe said, is that for transit professionals at the conference, service reductions would only be an "inconvenience," since remote and hybrid work is an option. Blue collar and service industry employees don’t have that flexibility, and the cuts would create additional hassles and expenses, such as figuring out different daycare arrangements for their kids.

Lowe gave an example of a Far South Side resident interviewed for the study who said that "When transit services decrease, I would be late for work... I'd have to figure out a way to get to work."

Solutions and the ghosts of New York congestion pricing

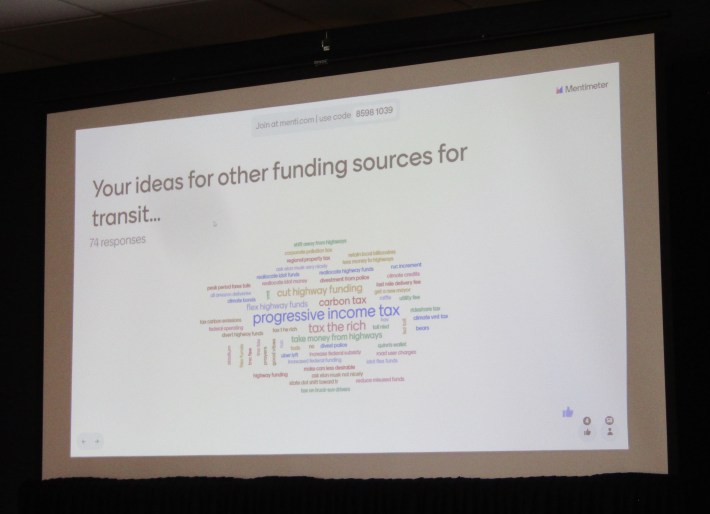

The panelists discussed several potential solutions, including increasing the state income tax, which they acknowledged was a heavy lift, and shifting some highway funding toward transit.

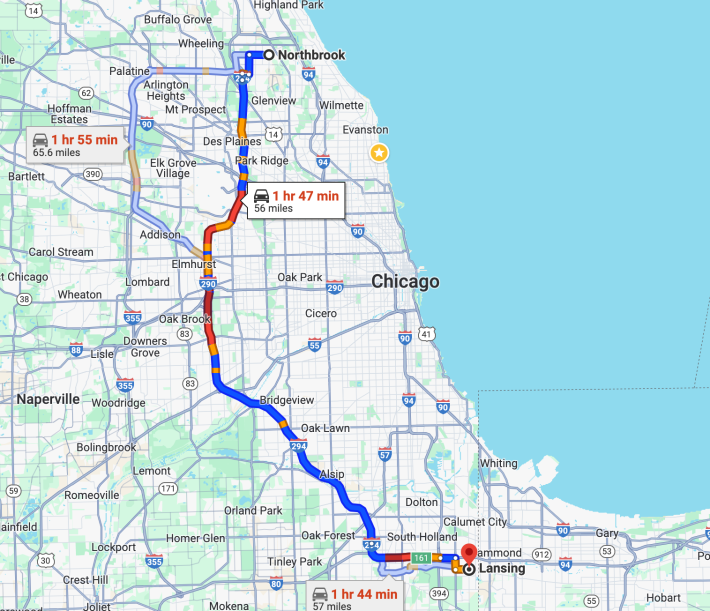

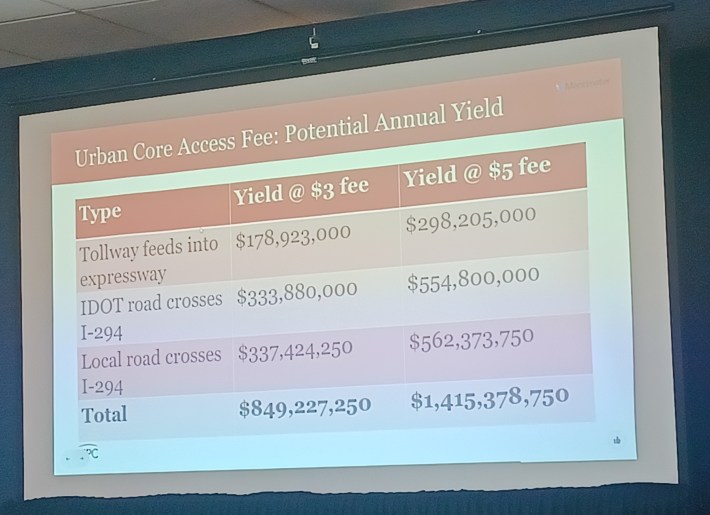

Bamonte suggested new taxes, mentioning creating a region-wide version of the Chicago tax on ride-hail trips, and a last-mile retail delivery tax on things like Amazon packages. But perhaps most radically, he proposed using the I-294/Tri-State Tollway as a "cordon," by collecting tolls from drivers using expressways within this boundary, which could be used to fund Chicago transit.

The tollway forms a half-ring between south suburban Lansing and north suburban Northbrook. Streetsblog readers may recall that Pace is studying using a portion of the tollway to provide suburb-to-suburb express services.

Bamonte argued that it would be more palatable than increasing tollway fees or putting in new tolls. He also argued that it wouldn’t require significant investments, since the technology to read tags on the passing cars already exists. "You don’t need additional tolling equipment to capture those movements. It’s a software upgrade that will impose that charge." [Bamonte later told Streetsblog that this statement, "referred to only the top line of projected revenue." Read his thread about his proposal here.]

He added that what would make such a strategy in Chicagoland different from the "New York City congestion pricing trainwreck" was that it would extend beyond the Chicago city limits, positively impacting the suburbs inside the tollway half-loop. And any concerns about disproportionate impact on low-income drivers would be addressed by Illinois Tollway’s existing discount program.

Asked who would need to be persuaded of the idea other than voters and elected officials, Bamonte responded, “This is an opportunity for the business community to step up.” He added that if Gov. J.B. Prizker could be persuaded to support the plan, he was less likely to flip-flop than New York state Gov. Kathy Hochul. "I’d like to think out political leadership can do much better," Bamonte said.

Did you appreciate this post? Please consider making a tax-deductible donation.