The Chicago Transit Authority is ditching diesel. Or at least that’s one of the goals included in Illinois’s new 2023 Transit Omnibus bill, passed by a coalition of lawmakers led by State Rep. Kam Buckner (D-26th). The bill mandates that as of July 2026, public transit agencies only purchase zero-emissions buses. But while the idea of a zero-emissions fleet is a good one, a quick shift to battery electric buses could put some major strains on transit agencies—especially the CTA. Transit advocates and elected leaders should make it clear to the struggling agency that while electric buses are a nice bonus, they can’t get in the way of the CTA’s efforts to deliver more frequent and reliable service.

First, some quick background. The CTA bought its first battery electric buses in 2014. The agency currently has 25 electric buses, and plans to fully electrify the 1,800-strong bus fleet by 2040. The state law builds on this plan. Based on a standard bus lifetime of 14 years, the CTA will need to start all-electric purchases by 2026 to meet its goal. Importantly, the law also includes an out clause—the CTA can continue to purchase diesel buses if funding for zero-emissions buses is unavailable, or the CTA lacks the necessary infrastructure (such as charging and storage).

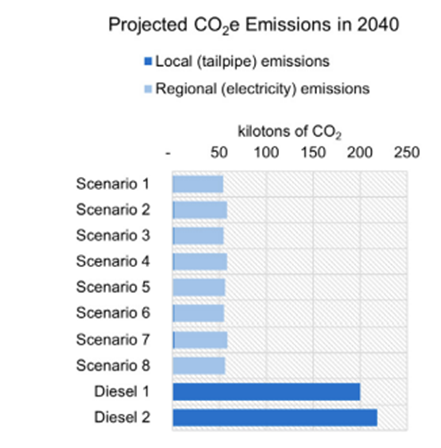

At first thought, this seems like a great idea. The world just experienced its hottest summer on record, and it’s no secret that more must be done to battle climate change. The CTA estimates that fully electrifying the bus fleet would reduce greenhouse gas emissions by the equivalent of 150 kilotons of carbon dioxide a year. Diesel buses emit a range of harmful pollutants, and the CTA is prioritizing the deployment of new electric buses in neighborhoods with the highest levels of air pollution (which are disproportionately Black and Latino communities and lower income). Plus, nobody likes standing behind an idling diesel bus on a hot summer day.

High costs, low reliability

But battery electric buses are a relatively new technology, and they come with their own challenges. First, they’re expensive. In 2022, the CTA estimated that shifting over to electric vehicles would cost $1.8 to $3.1 billion dollars, on top of the normal cost of maintaining the bus fleet. Part of that is because battery electric buses cost about $500,000 more per bus upfront. But since current batteries aren’t large enough to power the bus for a day, the CTA will likely also need to buy more of them—plus another $450 million for a new bus garage. That doesn’t count the cost of new charging or maintenance infrastructure. Notably, these higher capital costs swamp the operating savings associated with electric buses: total costs from 2022 through 2040 are expected to be $1.7--$2.9 billion higher.

Issues with range and battery life also impact bus operations. With current battery technology, only half of current weekday routes can be served by buses that charge overnight. For the other half, CTA envisions deploying a series of ‘on-route’ charging stations, to enable buses to charge during their routes. But this creates new challenges—requiring buses to go out of service and staff to oversee the charging process. Even worse, bus batteries can drain up to 40 percent faster in cold weather, when batteries function less effectively and more energy is required to heat the bus interior (diesel buses can rely on heat from the engine).

Bus manufacturers are struggling to deliver on their existing promises on battery life and reliability. Denver has cancelled outstanding orders due to reliability challenges, and Philadelphia has mothballed its electric buses while it re-evaluates the decision to go all-electric. Other transit agencies, including Madison and Juneau, Alaska have struggled with reliability and quality issues. The challenges aren’t limited to a handful of cities, either: electric bus startup Proterra recently declared bankruptcy, citing contracting and supply chain difficulties. When asked about the issue, CTA spokesperson Maggie Kilgannon said that the agency’s electric buses have “performed well” but didn’t provide details.

The new buses also present challenges for the agency’s workforce. Christof Spieler, a lecturer at Rice University and Vice President at transit consulting firm Huit Zollars, notes that there will be a learning curve for transit operators. “Large agencies know how to run diesel buses. They have a set of mechanics who know how to work on them, who know all the tips and tricks and have sets of spare parts to run those buses.” In the long-term, these issues will get worked out. But in the short term, battery electric buses are likely to yield higher costs and lower reliability. And the short term matters—the CTA is falling apart, thanks to a combination of service cuts and poor reliability.

If the CTA doesn’t get this right, higher costs and lower reliability of electric buses could compound the system’s existing woes and make it even harder to restore decent service. Not only would that be a tragedy for riders, but it could actually create *more* air pollution. In 2022, the CTA provided 212.2 million fewer rides (bus and rail) than it did prior to the pandemic in 2019. Assuming that Chicagoans replaced 30 percent of those trips with a car instead (a standard estimate for large cities), CTA’s ridership decline resulted in 377 million more car miles traveled and 150 kilotons of additional CO2 equivalent emissions.[1] Does that number sound familiar? It's the same amount of greenhouse gas emissions that the CTA projects to save by going fully electric.

Think about that: getting CTA ridership back to 2019 levels would have the same impact on the planet as fully electrifying the bus fleet. Plus, we wouldn’t have to wait until 2040. As Courtney Cobbs noted in Streetsblog last year, the best way to reduce emissions is to deliver better service. And while this article has focused on the climate impact, that’s only the beginning of the damage CTA’s poor performance has done to Chicagoans.

Backup plans for reliable buses

Zero emissions busses are a noble goal, and it’s certainly possible that battery electric bus technology will dramatically improve over the next few years. But hope isn’t a plan. The CTA needs better backup options if it takes some time for the technology to mature.

One of the easiest things we could do is to work with other agencies to buy in bulk. Spieler notes that right now, just about every US transit system buys a different bus. “US transit agencies tend to want really bespoke buses, and individual agencies have really complicated procurement specifications that mean you’re almost custom producing. Every agency’s bus is a little different, which has huge implications when you’re trying to run an assembly line.” In fact, Proterra cited those customization requirements as one of the key factors that pushed it into bankruptcy. Since electric buses require new designs anyway, an agreement on design standards across agencies could reduce manufacturing costs, and give the CTA and other partners more negotiating leverage when placing orders.

Another option would be to explore alternative zero emissions technologies. Many cities around the world run trolleybuses on overhead wires, including Philadelphia and Seattle. In an analysis of Boston’s (now-retired) system, transit expert Alon Levy (among others) notes that electric trolleybuses are “clean, reliable, and relatively inexpensive to maintain,” with a more than 100-year track record. They have particular advantages during the winter, because they don’t have to worry about battery drain. Looking farther abroad to cities with higher quality transit systems, Levy notes that Swiss cities are expanding their trolley bus networks, and Central European cities are rolling out In-Motion Charging, which allows trolley buses to run off-wire for short periods of time.

When asked about trolley buses, Kilgannon pointed out that the CTA hasn’t operated trolley buses for decades, cited maintenance challenges for wires during cold weather, and mentioned "practical and aesthetic considerations." It seems like it’d be easier for CTA to adopt trolley buses for the most battery-draining routes, and even if mechanics would need to learn new maintenance procedures, they’d at least be working with proven technology. Kilgannon did note that the agency is continuing to look at other zero-emissions alternatives to battery-electric buses, which is good news.

But if we get to 2026 and battery-electric buses are still costly and unreliable, the CTA should take advantage of the escape clause in the law. Ironically, that might be the hardest option. "Saying that you can’t follow through on electrification right now, is basically saying that you can’t follow through on one of the major political priorities of the people you report to," Spieler notes. "And that goes against the grain of everything that a transit agency is meant to do." I asked the Kilgannon about this option, and what might trigger the out clause, but didn’t get a response.

Memo to the CTA: Reliable service comes first

As dysfunctional as the CTA might be today, it’s at least attempting to deliver on the priorities given to it by the state. If it gets the message that electric buses are a priority, it’ll attempt to deliver on that priority—even at the expense of reliability or ridership. Buckner and his fellow lawmakers deserve real credit for including the out-clause in the bill. But the CTA needs to get the message: if there’s a tradeoff between reliable service and electric buses, service should come first every time.

Update 9/20/23, 2:00 PM: This article was amended to reflect the fact that Boston has recently retired its electric trolley buses. Thanks to commenter Dan Joseph for the update.

[1] Calculations assume an average trip length of 5.88 miles (based on Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning data for household size and vehicle miles traveled), and EPA’s estimate that 1 mile traveled in a passenger vehicle emits .4 kilograms of CO2.

Did you appreciate this post? Please consider making a tax-deductible donation.