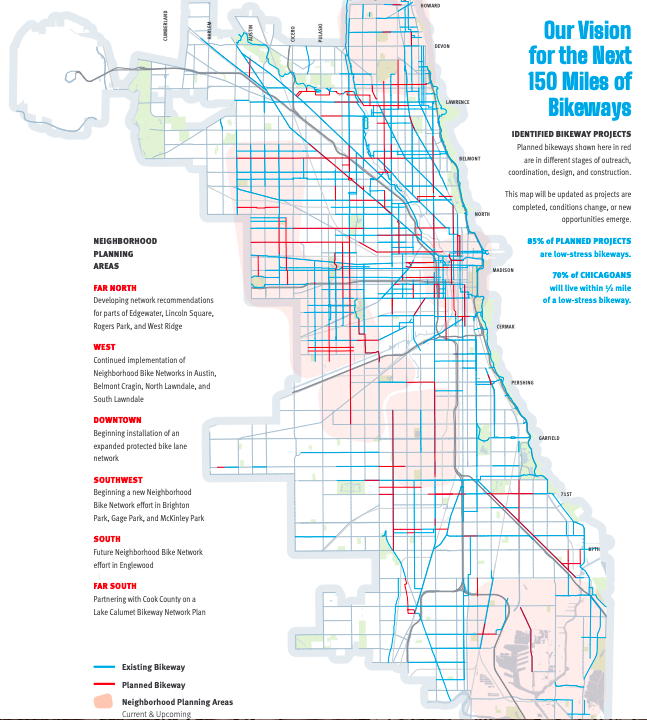

The Chicago Department of Transportation recently released a document entitled Chicago Cycling Strategy, outlining a long-term plan to improve cycling safety in the city and build, per a header splashed across two pages, the best bike network in the country. According to the document, this entails building 150 miles of new bikeways, 80 percent of which will be low-stress protected bike lanes, neighborhood greenways or off-street trails.

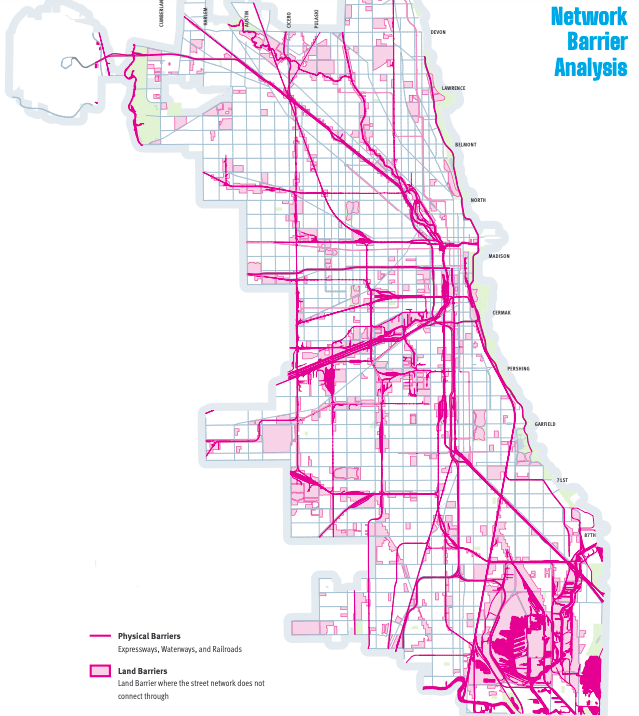

The agency seeks to stitch together Chicago’s current patchwork of protected bike lanes into a connected, crosstown grid, while simultaneously building out neighborhood-level bike networks to encourage residents to make more local trips on two wheels instead of four. The strategy is an update to CDOT’s 2021 Community Cycling plan and based on years of experience building successful and, in some cases, not-so-successful bike infrastructure projects.

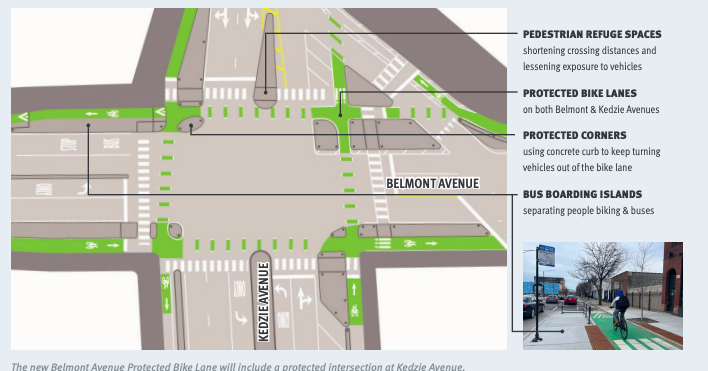

In the introductory section of the document, CDOT commissioner Gia Biagi states the strategy is intended to be flexible and evolve under changing conditions and assumptions. However, the document does name specific projects to be built over the next few years, including protected bike lanes on major arterial routes. One notable improvement is slated for Belmont Avenue between Kimball and Clybourn, connecting the Belmont Blue Line station to the 312 RiverRun trail system.

Chicago’s scattershot system of bike lanes is one big reason why the city has ranked (some would say unfairly) low on People For Bikes’ bike-friendliness city ratings year after year. Whether or not it makes any sense to place Chicago behind cities like Dallas, Phoenix and Los Angeles, the current situation of concrete protected bike lanes abruptly vanishing is dangerous and discouraging to many would-be riders. Availability of bike infrastructure often follows the boundaries of wards, where aldermanic support of bicycling—or lack thereof—can be jarringly visible.

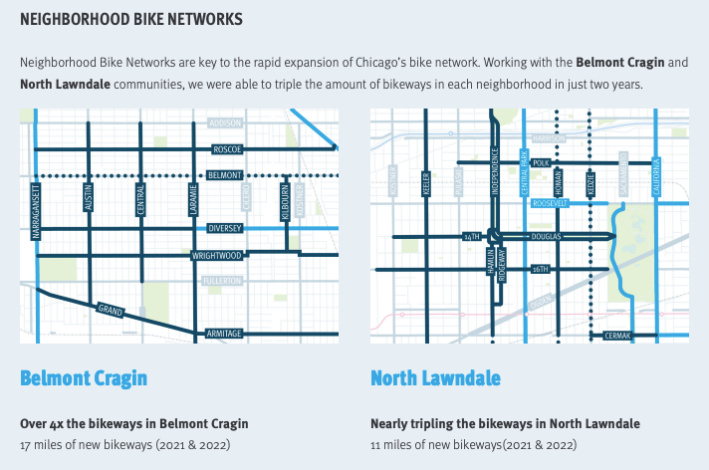

In an interview with Streetsblog, a CDOT representative stated that partnerships with trusted community members and the creation of neighborhood-level task forces that include advocates across sectors—including public health, housing, employment, environmental justice, youth services, as well as transportation—has made the case for the benefits of biking to community members and their elected representatives. The document points to recent successes North Lawndale and Belmont Cragin, which tripled and quadrupled bikeway mileage, respectively, in the last two years, through ongoing community partnerships. CDOT plans to continue spreading neighborhood-level bike networks from these nodes, moving south from Belmont Cragin into Austin and North Lawndale into Little Village.

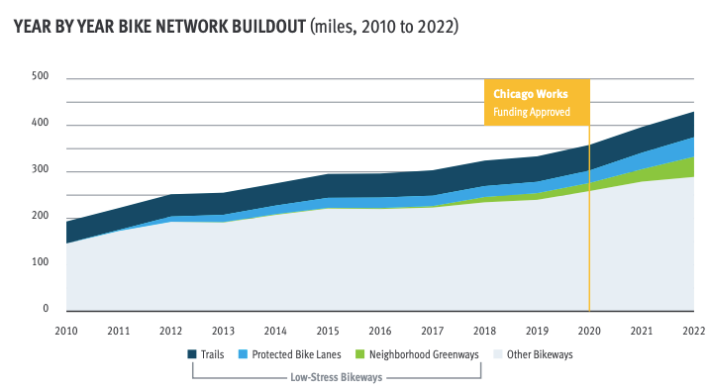

According to CDOT, Chicago historically averaged about 15 miles of new bike lanes each year until 2020, when the Chicago Works infrastructure funding program provided a valuable pot of dedicated money for bicycle and pedestrian infrastructure, doubling the amount of new bike lanes built each year. While the Chicago Cycling Strategy isn’t specific about timelines, CDOT expects that, with two more years of dedicated Chicago Works funding secure, the 150 miles of new bike lanes will be complete in three years or less.

The document emphasizes the importance of building community trust and interest in biking in neighborhoods with few to no bikeways, siting the removal of protected lanes on Independence, Douglas and Marshall Boulevards as a cautionary tale against installing new projects without sufficient community buy-in. Protected lanes and greenways have since been installed on and around these corridors, after years of outreach and collaboration with community leaders in North Lawndale. CDOT states this experience helped shape a plan for bike network development tailored to varying levels of biking visibility and existing infrastructure.

The CDOT rep said building a cycling culture in areas with low biking visibility through bike education and access programs, alongside community involvement in planning, is critical to success. Essentially, it's not enough to drop a bike lane in a neighborhood.

The strategy closely parallels the Active Transportation Alliance’s “Bikeways for All” campaign, which calls for 180 miles of new bike low-stress bike facilities. “The Chicago Cycling Strategy is an important step forward and provides a set of concrete goals and benchmarks that advocates like us can use to ensure the city follows through on its commitment to create safer streets for people on bikes,” ATA advocacy director Jim Merrell said in a statement.

Not all advocates are hopeful about the new strategy. In an interview with the Chicago Sun-Times, Bike Lane Uprising founder Christina Whitehouse expressed skepticism about the future of a plan issued a few weeks before a new mayor takes office. She did however make this statement before the run-off and election of Brandon Johnson, who has expressed support for biking accommodations, was endorsed by the Safe Streets for All Coalition, and had a significantly more substantial transportation platform than his opponent Paul Vallas.

Since CDOT states the document is a reflection of what has and hasn’t worked in bicycle planning, building on growing momentum and excitement for cycling in Chicago, there's reason to be cautiously optimistic that we'll see a bikeway renaissance in our city in the coming years.