This post focuses on the Chicago Mobility Collective breakout session that focused on street design to improve bus service. Streetsblog may run coverage of other breakout sessions that focused on pedestrian and bike matters in the future. The meeting took place during the same time as the ghost bike installation for youth mentor Sam Bell, 44, in River West. To highlight Chicago's traffic violence epidemic, some people Zoomed in to the meeting from the memorial using a background with a white bicycle and the words "I'm currently at the ghost bike vigil for another cyclist killed on Chicago streets." Others posted a "Vision Zero Chicago 2022 Report Card" with crash fatality stats. About 140 people attended the meeting altogether. - Ed.

Transit advocates who took part in the transit portion of the September 29 virtual meeting of the Chicago Mobility Collaborative argued that the city should be putting more resources towards full-fledged bus rapid transit instead of more incremental measures – and that the Chicago Department of Transportation is creating a false choice between installing safe bike lanes and putting in BRT.

This was the second quarterly meeting of the collaborative, which replaced the Mayor's Bicycle Advisory Council and Mayor's Pedestrian Advisory Council meetings, which were shut down in early 2020 by the COVID-19 pandemic. This time around, attendees were sorted into four breakout rooms: cycling improvements, pedestrian safety, bus-related streets improvements, and community engagement. As someone who is most interested in transit, I asked to be placed in the bus group.

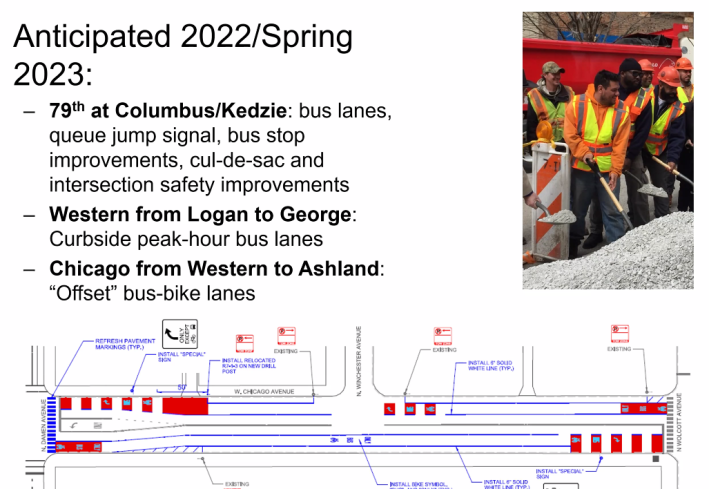

During the breakout session, CDOT and CTA officials touted the express bus corridors the city already has, the downtown Loop Link system and parts of South Side’s J14 Jeffrey Jump route, as well as other measures the city has taken to speed up bus traffic, such as what the city calls Bus Priority Zones (short stretches of bus-only lanes in high-congestion areas, typically only in effect during rush hours), curbside bus lanes, boarding islands, and transit signal priority. The officials got many questions about creating full-fledged BRT, including long stretches of well-enforced car-free bus lanes. Their response boiled down to the fact that there is often considerable community opposition to converting street parking or mixed-traffic lanes to make room for bus lanes, so they prefer to focus on more incremental changes that are less politically challenging.

But the transit advocates in attendance argued that BRT is hampered by a chicken and the egg situation. Chicago doesn’t have any full-fledged BRT corridors, including prepaid boarding and camera enforcement. Therefore, it's difficult for residents to understand how a robust BRT system would make transit service faster and more reliable, attracting more riders, taking cars off the road, and ultimately reducing traffic congestion and parking demand.

The advocates added that CDOT and the CTA haven’t been transparent about what kind of pushback to more robust transit improvements they've gotten from neighbors and alderpersons, which makes it harder to for pro-BRT residents to respond to this "Not In My Back Yard"-style opposition. Toward the end of the session, the officials argued that there's more support for bike lanes than BRT, a characterization that Active Transportation Alliance staff present forcefully pushed back against.

What bus infrastructure the city currently has

Jason Meter, the CTA’s senior manager of traffic planning, cautioned that, while speeding up buses is a priority because it improves reliability and make transit more attractive, “It's not one size fits all” because “different corridors have different needs.” He touched on the signal priority, adjusting stoplights so that the green phases shorten or extend to make it easier for buses to get through intersections. This tactic has been piloted on the section of Western Avenue between Howard and 95th Streets, and on Ashland Avenue between Cermak Road and 95th, as well as in Bus Priority Zones.

Meter also talked about pedestrian boarding islands, such as the ones that were put in on the stretch of Jackson Boulevard that runs through Austin’s Columbus Park as part of a road diet project, and similar “hybrid bus bulb/bike lanes” where bike lanes that run between traffic lanes and street parking temporarily turn closer to the sidewalks to create space for bus islands.

Meter also mentioned smaller improvements such as a pilot to add tactile bus stop signs on Madison Street to help riders with visual impairments, and adding concrete pads at some bus stops that were previously little more than a patch of dirt with a bus stop sign. Looking towards the future, Meter said the CTA has secured grants to do more Bus Priority Zones “to unsnarl the buses at pinch points.”

The transit agency also continues to work on electrifying its fleet. “Currently, we have 13 Proterra buses,” said Jennifer Henry, the CTA’s senior manager of transit planning. “We expect 10 more by the end of the year.” She said the agency is investing in adding charging stations at the route terminals, since it found that to be more efficient than adding multiple stations along the route.

BRT Blues

Many of the questions and comments revolved around BRT in general and the ill-fated Ashland BRT project specifically. That proposal called for converting two mixed-traffic lanes on the generally five-lane street to center-running bus lanes with median stations, but it was shelved due to NIMBY opposition from some neighbors and merchants. Henry responded that any potential BRT project still faces headwinds due to the tendency of motorists to oppose projects that might make driving and/or parking slightly less convenient.

“The opposition [to the Ashland BRT] was real, and some things have changed since then,” Henry said. “There was a lot of grassroots opposition to taking away street parking." The proposal would have preserved 92 percent of the parking spots along the corridor. But I think we do need to be able to explain the trade-offs and the benefits as well, because there’s going to be resistance to changing the status quo.”

The proposed Pace Halsted Arterial Rapid Transit bus line was originally going to have bus-only lanes. But community concerns about street parking, as well as some other aspects of the street design proposal, led Pace to only keep the bus lanes on the slowest section of the route.

Transit 4 All campaign organizer Jose Manuel Almanza pressed the officials on the specific obstacles they are facing to get BRT off the ground. (The Transit 4 All campaign / Chicagoland Transit Rider's Union is being organized by Chicago Jobs with Justice.) Kurt Fackhitz, CDOT engineering manager, responded that the transportation department's and the CTA's current approach is about getting the most out of the funding they have and being able to “spread those benefits to where they can make a positive impact.”

However, there's currently an unprecedented opportunity for Chicago to line up funding for a robust BRT system. The U.S. has a new $1.2 trillion federal infrastructure bill, Illinois has a nearly $45 billion state capital plan, and the city of Chicago has a $3.7 billion infrastructure program.

Meter added that, while funding concerns are a factor in why gold-standard BRT is not currently on the table, so is the NIMBY opposition Henry mentioned. “[BRT] takes a buy-in from the entire community, and there's very vehement opposition to [taking away] any parking, whether it's paid parking or not. There are a lot of community members and businesses that are opposed to it, a lot of elected officials that are opposed. That’s the challenge we have.” He added that the Mobility Collaborative meetings could help turn the tide, since they provide a forum for the CTA, CDOT and transit advocates to work together.

Julia Gerasimenko, advocacy manager at ATA, noted that, “in terms of barriers and public opposition, it's important to have a proof of concept, which we don't have in Chicago beyond the Loop Link.” Due to factors like the scrapping of the original plans for prepaid boarding, and poor enforcement, Loop Link has resulted in only modest bus speed gains.

David Powe, the alliance’s director of planning and technical assistance, wasn’t satisfied with Fackhitz’s and Meter’s explanation. “It seems that the city and CDOT and CTA are being as indirect as they can be about those barriers [to building robust BRT. Is it] parking? Aldermanic prerogative? The parking meter deal?... People want to see true BRT along very long corridors with [multiple] lanes. We want to hear why that's not happening.”

Meter reiterated the earlier reasons stated, and added that there is “competition for space with bikes and buses,” adding that he personally cycles more than he rides the CTA. “I'd be willing to bet that the bike breakout session is better attended than this right now,” he aded. “There’s a lot more enthusiasm for [biking], for better or for worse.”

Powe responded that the notion that streets can either have BRT or safe bike lanes is “a false choice,” add that his organization would never pit transit riders against bike riders. (And, of course, many people who commute by the CTA also use bikes for transportation. “So please refrain from using that [talking point] in the future,” he said.

The breakout session ended shortly after that, but in his remarks after the full meeting reconvened, Meter said that he believed that the conversation was productive. “We were in a good session and we got cut off."

Correction 10/7/22, 12:00 PM: This article previously misidentified the Transit 4 All / Chicagoland Transit Rider's Union campaign as being led by the Active Transportation Alliance. In reality the campaign is being organized by Chicago Jobs with Justice, and ATA is part of the coalition. Apologies for the error.