In December Chicago Mayor Lori Lightfoot picked Gia Biagi, who previously led the urbanism and civic impact practice for Chicago’s renowned Studio Gang design firm, to be commissioner of the Chicago Department of Transportation. Needless to say, having spent half of here tenure during a global pandemic, as well as serving during the recent George Floyd protests, Biagi has not had a typical experience as a CDOT chief.

Last week I caught up with Biagi for her first Streetsblog interview, during which she revealed that she lives in Old Town and not only commutes by bicycle "all over the city," but she's also a member of a bike racing team. We discussed the city and the department's response to the COVID crisis, including the question of whether, unlike many peer cities, Chicago failed to take advantage of historically low traffic volumes to make more room for transit, walking, and biking. The interview has been edited for length and clarity, with a bit of commentary from me in italics.

In addition to the topics covered below, we also talked about the decision to essentially eliminate bus-only lanes from consideration in the upcoming North Lake Shore Drive reconstruction. I'll include that conversation in an upcoming post.

John Greenfield: [I asked for an update on upcoming bikeways, which CDOT provided after the interview. Biagi then brought up the departments plan to quadruple the amount of bikeway restriping this year.]

Gia Biagi: I’m a cyclist and that’s something I notice all over the city, that one thing we really need to to is really make sure that the bike lanes that we do have are refreshed. Last year we did about 10 miles of refreshing those markings and this year we're going to do 40. That's significant, because when those markings get faded, it can feel like the bike lane's not even there, So it's really important that we make sure we're doing that ongoing maintenance throughout the system.

[The restriping is being funded by] Divvy program Lyft sponsorship, and a couple of other pots of operational dollars. We're cobbling it together and we've got to prioritize. Obviously [during the pandemic] we're in a different environment financially as a city, but we thought about the challenges that transit is seeing and what we could do to really enhance mobility and alternative forms of that, so we wanted to make sure we were investing in the cycling network as much as we could.

JG: A lot of cities around the world have been doing pandemic cycling lanes. Car traffic has been light during the pandemic, so cities have been converting parking or travel lanes on main streets to high-capacity bikeways. Why did Chicago basically not do anything to create more room to make more room for biking, walking, or transit until Phase 3 reopening started on June 3? [The Leland Avenue Slow Street (the city is calling it a "Shared Street") debuted on May 29.]

GB: I'd argue with the premise. We have been doing things. We're the only major transit system in the country that never stopped running, and that is significant and challenging. And part of CDOT's goal is working in partnership with the CTA.

[The CTA essentially maintained full frequency on all bus and train lines, including ones that have seen minimal ridership during COVID-19. Some have argued that the transit agency would have been wiser to cut frequency on little-used lines to save money and focus more resources on lines used by essential workers on the South and West sides, such as the #79 79th Street bus, that have experienced dangerous crowding during the pandemic.]

Our approach has definitely been different [than other cities], and part of that is that it's really important for us to think about the bigger picture. Part of that work includes listening really carefully to communities about what they would like to see happen. You can point out other cities like Oakland doing 74 miles of [Slow Streets] and New York doing what they're doing. Our approach was a little more methodical, really going slow, because we think that if we go slow, we can go smooth, and if you go smooth you can eventually go fast...

The other things that we did during COVID, for example, was spending $450,000 [to subsidize] half-price Divvy memberships and dollar Divvy rides, and to give healthcare workers free memberships, from the day the Illinois Stay at Home order started [March 21] through June. That was a significant effort to make Divvy a little more accessible to folks during this period.

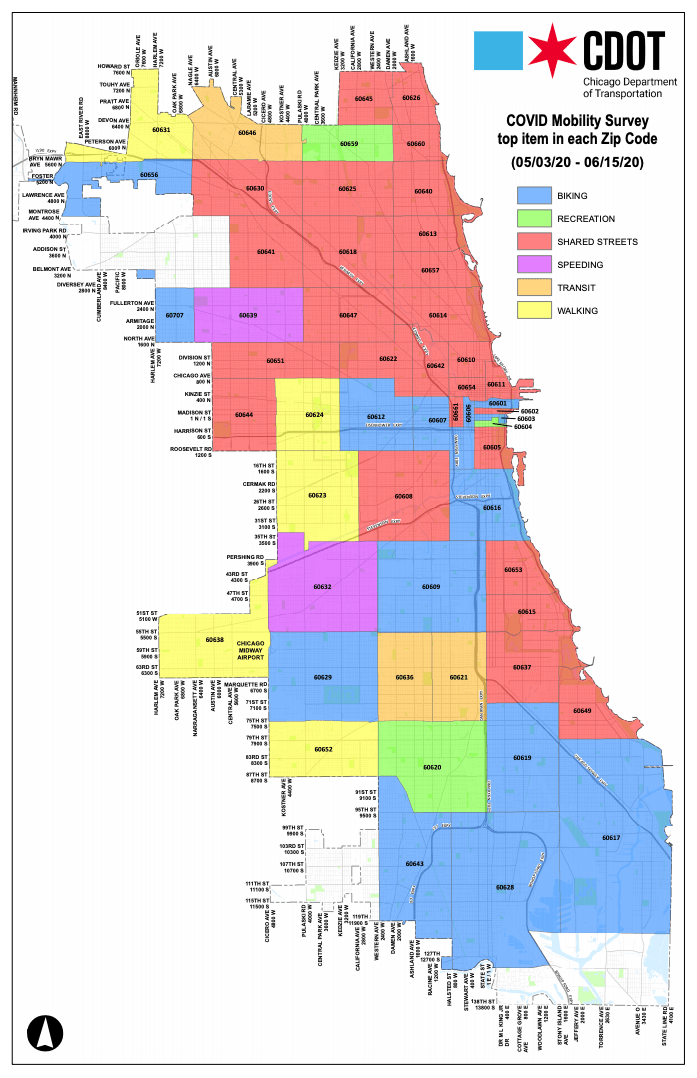

And so I think it's a combination of thinking methodically, looking through the plans that we've done, and doing outreach. And outreach is slow, but we were working hard to make sure that we heard from many parts of the city and understood the differences. And we've tried to be transparent about where we're hearing from across the city, including the map with over a thousand [Covid Mobility] survey respondents, but then also looking at what are people talking about, what is the most common thing we're hearing?

I haven't read all thousand, but I've read a couple hundred of what's coming in the door, and it's very different. In some parts of the city we've heard, "We don't want a [Slow Street], we don't want a closed street, but we do want you to hustle up on your construction projects," like road construction or pothole work, and that's something we've been trying to do, taking advantage of the low traffic.

Other parts of the city have said, when it comes to [pedestrianized Cafe Streets], "We prefer to not [open] the street because curbside pickup is really important." And other parts of the city are saying, invest in our bike network, and other areas are saying they want [Slow Streets].

JG: I heard what you said about the need to get lots of community input on transportation initiatives during the pandemic. However, a strong argument could be made that we had this unusual situation where traffic dropped dramatically during the pandemic, when we could have done bus lanes, we could have done main street bikeways, all these different initiatives that are politically really difficult to do during normal times, and we missed the boat by not really doing anything until traffic started to return to normal again. We're probably going to face a spike in driving since people are avoiding transit. What do you think of that argument that Chicago missed the chance to make major changes to our streets to make them less car-centric?

It seems like it's going to be politically very difficult now to, say, convert a lane of Clark Street to a dedicated bus lane, because people will say we need all the lanes for the existing amount of car traffic. So what's your response to that?

GB: I appreciate the question. I think that's something we've been thinking a lot about. But we were trying to navigate across a couple of things. As much as what you do matters, how you do it matters too. It is of primary importance that we do engage people in the world around them and what's happening in their neighborhoods. That process matters because it will help to define what we do that's meaningful, and people recognize that.

There are lots of boats. I don't think we missed any particular boat on this. In fact I think we helped create an appetite for a different kind of city as we come back to it.

Certainly we are are looking at those kind of bus-priority zones and lanes, temporary ones, we're in conversation with CTA about that, looking at where it makes the most sense to roll those out... We are very close to discussing what those streets are. It's just really important that we connect the dots. Obviously there a lot of factors in play. I would think in the next week or so we should be able to talk about what those streets are...

We're building a movement here. There are some things, perhaps that cities need to do by fiat but not everything.

[Mayor Lightfoot's decision to abruptly close the city's main car-free commuting routes, the Lakefront Trail and the Bloomingdale Trail, for nearly three months springs to mind as an example of a pandemic decision made by fiat, with zero public input.]

This is an opportunity to make sure that community itself gets to define what we do. So we're working on a lot of these threads and we appreciate everyone's patience in that regard but I don't think we missed a boat at all.

JG: You've been at CDOT for several months now. How has your experience been?

GB: Obviously [the pandemic] has been a unique period. I am really impressed with the team here, the incredibly dedicated people that get up every day, whether they're fixing the signals and the roads, or they're doing planning, the overall verve and spirit here is really good.

But I'm also excited about getting in a conversation with the city as a whole. How do we leverage our streets, how do we lean into them and say, OK, our streets are a place of protest. They're a place of play, they're a place of movement. They're all of these things in our lives. How do we put Chicago on the trajectory for that future street, that next thing. How do we define our streets in a way that we haven't before that's not just about throughput and numbers of users and all of the math, but how is it about our quality of life.

And the possibilities here could influence the economic prosperity of every neighborhood. The possibility for civic engagement, and re-knitting together the ties of people across streets, across neighborhoods. That possibility is in the hands of an organization like CDOT. The potential is pretty incredible.