Over the next few months, the Center for Neighborhood Technology will be hosting workshops and webinars on equitable transit-oriented development (eTOD). These include topics such as new technology and eTOD and social service delivery in eTOD.

Earlier this week, CNT hosted a workshop exploring the impact of parking requirements on eTOD. Peter Haas, chief research scientist at CNT, was the first presenter of the workshop.

Some benefits of eTOD outlined in the presentation include reduced transit commute times, public health benefits, and the creation of more affordable housing. However, some of the benefits of eTOD have been overshadowed and undermined by the growing correlation between upscale TOD and the displacement displacement of longtime residents. For example, within a half mile of the California Blue Line station in Logan Square, 39 percent of units with rents under $1,000 have disappeared since 2000, according to CNT. When TOD doesn't serve residents of all income levels, it doesn't help to make our communities more equitable.

After housing, Haas said, transportation is the second highest cost to a household budget. That expense is particularly steep when a household is car-dependent. During the workshop, Haas also walked the audience through CNT’s eTOD Social Impact Calculator. This tool allows users to analyze financial, social, and environmental benefits of eTOD projects in Cook County. For example, if you plug in an address near the aforementioned California stop, you can see the number of grocery stores within a mile of the station, and and jobs accessible via transit within 30 minutes, among other data. The calculator provides a good idea of the potential benefits of eTOD at a location.

The next presenter was Lindsay Bayley, senior planner at the Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning. She noted that the benefits of improving transit access and reducing auto dependence include making a neighborhood more affordable and equitable, and less of a drain on city services.

Bayley gave a brief overview of the history of Chicago’s zoning requirements for parking. The first zoning ordinance implemented in 1923 didn't include parking requirements. Our city became much more car-dependent over the next three decades, an in 1957 there was a major overhaul of the ordinance that involved thoroughly codifying parking requirements. In 2004, a new zoning ordinance was approved, which didn't change the parking requirements, but added some parking maximums were. In 2013, the city's first TOD ordinance was passed, which halved the usual parking requirements within 600 feet of transit stations. In 2015 the ordinance was strengthened by expanding the TOD zones and essentially eliminating the parking requirements in these areas altogether.

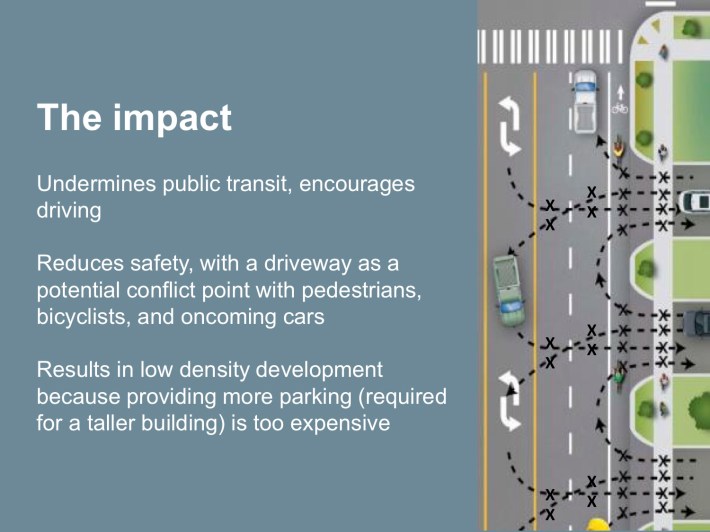

“A city that can reduce dependency on cars is going to be more equitable,” Bayley said. “Parking requirements also undermine public transit.” Parking mandates, Bayley added, also reduce safety, because driveways cause potential conflicts between drivers entering and existing parking areas and pedestrians, bicyclists, and other drivers. They can also result in lower-density development, since providing the parking required for taller buildings adds to construction costs.

Parking requirements can also discourage new development without subsidies, serve as a barrier to redeveloping existing buildings, make affordable housing more expensive to build, and encourage the construction of taller buildings that are no longer at the "human scale," Bayley said.

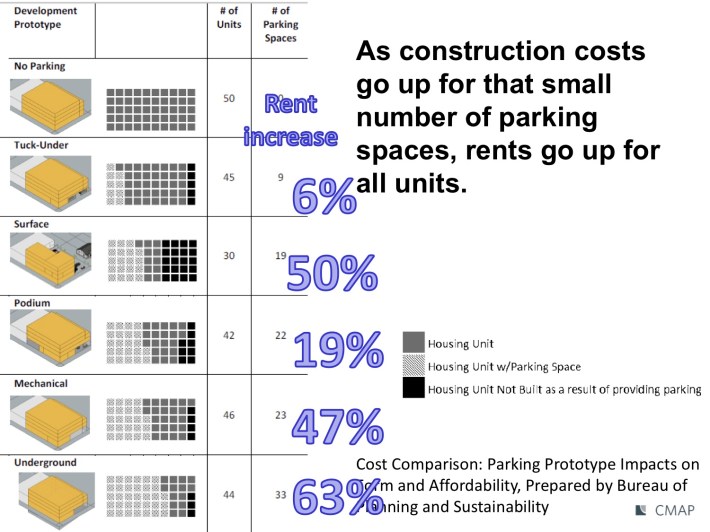

Even a small number of parking spaces can make construction more expensive, which causes rents to go up for all units. Eliminating minimum parking requirements, Bayley said, does not mean new buildings won't include any parking, but that developers will have more flexibility to respond market demand. Some cities that have eliminated minimum parking requirements include London (2004), Mexico City (2017), and San Francisco (2018).

In the last part of the presentation, Bayley went over the equity piece of TOD and parking minimums. Parking requirements are more likely to burden poor people, since the inclusion of a parking space in the cost of an apartment raises its rent, and because they are less likely to own cars. Dollars spent on parking spaces are dollars not spent on building housing for people.

Some strategies to promote equity include unbundling parking from housing costs by charging a separate rent for spots, and selling parking separately from the cost of a condominium. A holistic approach to transportation should be pursued, including on-street parking and residential permits.

Making eTOD work also requires the city to prioritizing transit options for residents by increasing train and bus service. “It’s a lot easier to increase capacity on transit than increase capacity for cars,” Bayley said. “Our bus system has the potential to move more people.”

To learn more about CNT’s series on eTOD, go to their events page.

![]()

Did you appreciate this post? Consider making a donation through our PublicGood site.