Few players in Chicago's transportation planning and advocacy scene have as impressive a resume and as deep an institutional memory as Jacky Grimshaw, the Center for Neighborhood Technology’s vice president for government affairs. She's been with CNT since 1992, including creating and leading the nonprofit’s transportation and air quality programs for over a decade, and spearheading its Transit Future campaign for a new revenue stream for regional transit at the Cook County level.

Grimshaw has also served on the boards of the Chicago Transit Authority and the National Academy of Sciences’ Transportation Research Board’s environmental justice and public involvement committees. She recently completed terms on the women’s issues in transportation committee.

Before joining CNT, Grimshaw was a researcher in hematology and gastroenterology. She has also worked in both state and federal government, for the Chicago Public School district, and as a political advisor to Harold Washington, Chicago’s first Black mayor.

I recently sat down with Grimshaw at her home in Hyde Park to discuss her unorthodox career path, what she learned from working for Washington, her efforts to promote equitable transit-oriented development, why the Transit Future campaign is currently stalled, what she’d like to see from the next Chicago mayor, and more.

James Porter: You formerly worked as a researcher studying matters related to blood and disorders of the stomach and intestines. What made you switch careers and become involved in transportation planning and advocacy?

Jacky Grimshaw: Serendipity. I left hematology research because the guy I was working for and I had a disagreement because my great-grandmother died while my husband and I were on vacation, and there was an airline disruption. We couldn't get back from Miami Beach on time. We had to do a variety of transportation modes to get back from Miami Beach. So I was late getting back from my vacation, and [the guy I was working for] thought I was disrupting his research schedule. I was very stressed from my grandmother dying and the trouble getting back, so I said "Don't need your job" and I walked out. [Laughs.] I think I left in the early seventies, I don't remember exactly...

JP: That seems like an abrupt switch...

JG: No, it wasn't abrupt. It was all of these various stages along the way. I went from gastroenterology to public policy. I started because my good friend [civil rights activist] Al Raby convinced me that I needed to come and help out the governor, who was having difficulty with some African-American vendors who were supposedly supplying services for [the Illinois Department of Children and Family Services.] So, he recruited me to go in and work for the governor, which I did.

That started me off in my life in public policy. How I got to transportation is, again, doing the public policy stuff. I was working for the state of Illinois -- I did the governor's office, I did the department of personnel, I did the work incentive program, which was really run by two agencies: the Department of Health and Human Services and the Department of Transportation. So I got to experience a lot of transportation policy just doing the work incentive program.

JP: What are you currently doing at the Center for Neighborhood Technology?

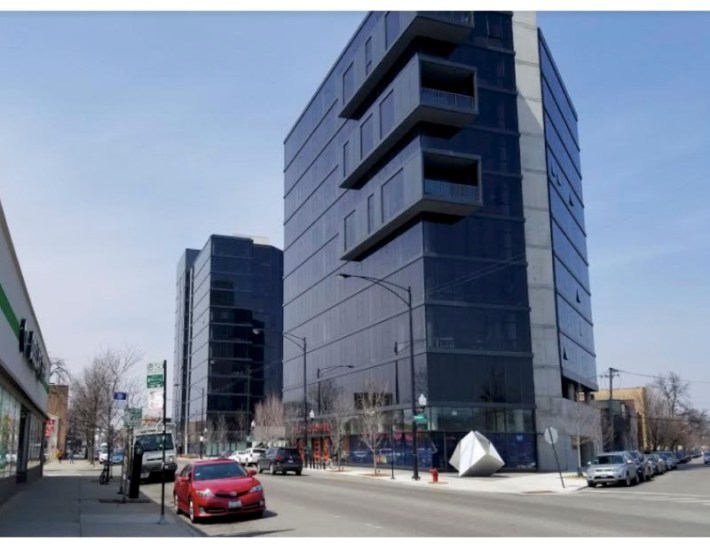

Right now I'm working on two major program areas. One is equitable transit-oriented development. In urban areas, particularly in the city of Chicago, it was really developed on the same concept of transit-oriented development. As we went from streetcars to trains to buses, we kind of lost that development. We became more of a sprawling community.

I'm sitting here looking down at Woodlawn. When I grew up, the [Jackson Park branch of the Green Line] came all the way up to Stony Island. It was a prosperous street with all kinds of small retail shops and things of that sort. The train came down, and the development went away. So now you have a suburban-type development from Cottage Grove pretty much to Stony Island. You have some housing but you don't have much commercial activity, because the density isn't there. After World War II, we have lost that kind of urban development pattern.

Starting probably in the Nineties, we started to reemphasize development around transit stations. As that kind of took off, people recognized the advantage of being right next to the train station, and it became a vehicle for luxury housing. So the people who have lived in the community for ages got pushed out in favor of this more luxury, high-end kind of housing.

We started to push back on that; we needed to maintain affordability at these transit stations. People who needed transit also needed affordable places to live. If you're talking about folks of lower and middle-wage income earners, they need to reduce their household expenses by having an affordable form of transportation. Well, if they're being pushed away from transit, to places where they need a car, there goes their affordability because transportation costs so much.

So we've been pushing on this equitable transit-oriented development thing. We worked with some [community development corporations] here in the city. We did workshops with them to identify what they were having difficulty with, and we worked with them to develop a tool called the eTOD Social Impact Calculator. So that's one of the things we're doing.

And then we had this opportunity, it was a national competition from an organization pretty much based in California that's called SPARCC, which stands for Strong Prosperous And Resilient Communities Challenge. They started with a hundred cities, they narrowed it down to about ten cities, and asked those ten cities to send in requests for qualifications to compete for participation in this program, which was geared towards real implementation money. Communities have a thousand plans, but then it comes to "Okay, we got a plan" - where's the money to implement?” Nowhere to be found. This was a program that actually provided some implementation money.

So we did our RFQ, and then we were asked to do a request for proposals, which we did, and we were successful. We built our RFP around, as we call it, "The Tale Of Two Cities." We have the part of Chicago where you have the train system, and you have all these luxury high-rises. And you have a high cost of living. And then you have the train system that also runs through places where there’s been disinvestment. There’s a lot of available land, but there’s no affordable housing, and no retail. We want to see if we can work and bring equitable, affordable housing to the strong market areas, and bring development to these weak-market parts of the city. Between those two things, that's taking up most of my time.

JP: You’re an African-American woman in a field that has historically been dominated by white men. Do you feel that that has presented any particular challenges for you and, if so, how have you dealt with those?

JG: Everything I've done has been dominated by white men! [Laughs.] So if you go into the medical research community, when I started, it was primarily white physicians. Gastroenterology at the University of Chicago -- when I went in there, again, it was pretty much a white-male-dominated field. The development of policies at the gubernatorial level in the state of Illinois was probably more integrated in terms of races and sexes. So, what else is new under the sun, as we say. [Laughs.] I was educated at Marquette University [in Milwaukee]; most of the African Americans on campus were athletes. Very few African Americans were non-athletes. You could count 'em on one hand.

JP: What has changed in this respect during the time that you’ve been in the field and, what still needs to change to make the transportation planning and advocacy field more representative of the populations that it serves?

JG: I think it's holding government accountable. There was a national transportation bill that really got these changes started. One of the crucial things that those of us outside of Washington advocated for was public involvement in transportation planning. One of the things we advocated for is that transportation engineers cannot come and make major infrastructure changes without talking to the people who live there. That was a major innovation in 1991 when the National Transportation Bill was passed. We have been advocating and advocating to get that implemented. If it's going to affect you, then you need to know about it, and you need to be able to say yes, no, maybe so, right? But not just [have them] come and bulldoze your house.

JP: What did you learn from your time as an advisor to Harold Washington, and how does that influence what you do now?

JG: Harold Washington was one of the smartest people I know. My friend Barack [Obama] is pretty damn smart, but Harold was that and more. They're both brilliant people, but what I learned from Harold was not only the commitment to people, which Barack also has, but also how to take the input from ordinary citizens and solve their problems. Harold would get his information from being out there in the streets. What I learned from Harold is that you can't learn everything vicariously. You gotta get out there and do hands-on touching, feeling, getting input directly from people, then taking that input along with what you know from research or other viewpoints, then figuring out the right solution.

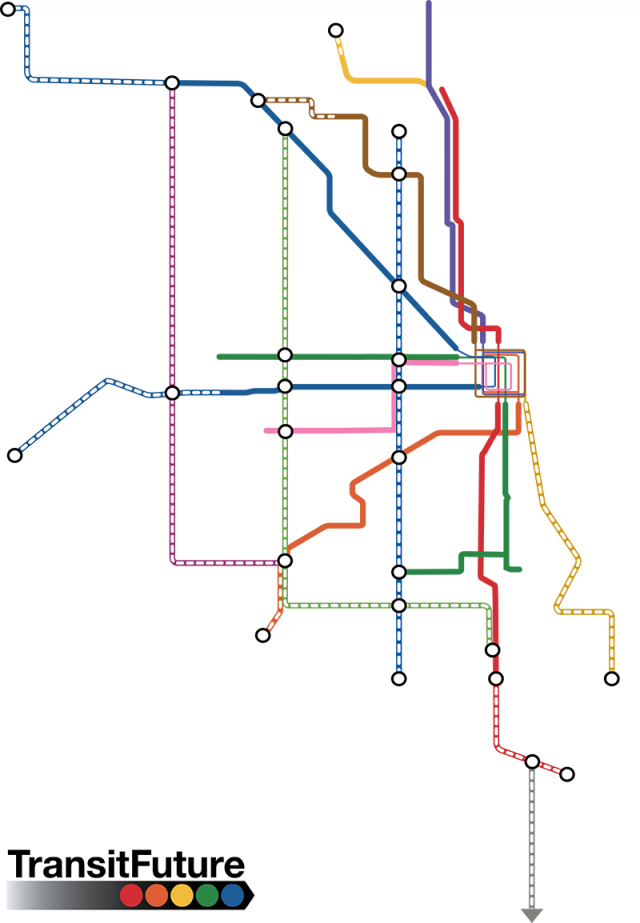

JP: You’ve led the Transit Future campaign to create a dedicated funding source for Chicago area transit at the Cook County level. We haven’t heard anything about that effort for some time. What’s going on with it?

JG: When Toni Preckwinkle first ran for [Cook County] board president, we had just gotten a one-percent sales increase from Todd Stroger, who was the previous president of the county board. Toni ran on reversing that. We had wanted to repurpose that one percent to improve transit in the county. Toni supported Transit Future, but she'd run on that commitment to give back that one-cent sales tax. Promises made, promises kept. The idea was to look for another source of funding to make Transit Future happen.

Well, what did we do? We got Bruce Rauner as governor. We didn't have a budget for two and a half years. It totally screwed up the finances. Part of the city and county's finances come from the state. And when the state is broke, and the state is not passing a budget, it affects everything. So, essentially, Bruce Rauner killed my Transit Future with his dumb policy, and you can quote me on that. I have not given up on Transit Future, because we still need to have it, but we have to wait until we get a more stable financial future.

JP: Mayor Emanuel recently announced he’ll be stepping down. What would you like to see from the next Chicago mayor in terms of transportation policy?

JG: Rahm has some good ideas. One of the things that Rahm just launched is this mobility task force, headed by a former secretary of transportation [Ray LaHood.] The mobility task force, as I understand it, is to look at how to improve mobility in the city of Chicago. My thought is that we can't be parochial. We are in a six-county region. We have people from outside of Chicago coming into Chicago, congesting our roadways. You look at the Kennedy in the morning, you look at the Edens in the morning...we have to look at, in a regional context, how can we improve mobility for both those folks who live in the city, and maybe have to get out to the suburbs, as well as those folks in the suburbs having to come into the city. For me, it can't just be city Of Chicago. That's where I'd start. The positive legacy of Rahm wanting to do this mobility task force is a base upon which the next mayor can build.

![]()

Did you appreciate this post? Consider making a donation through our PublicGood site.