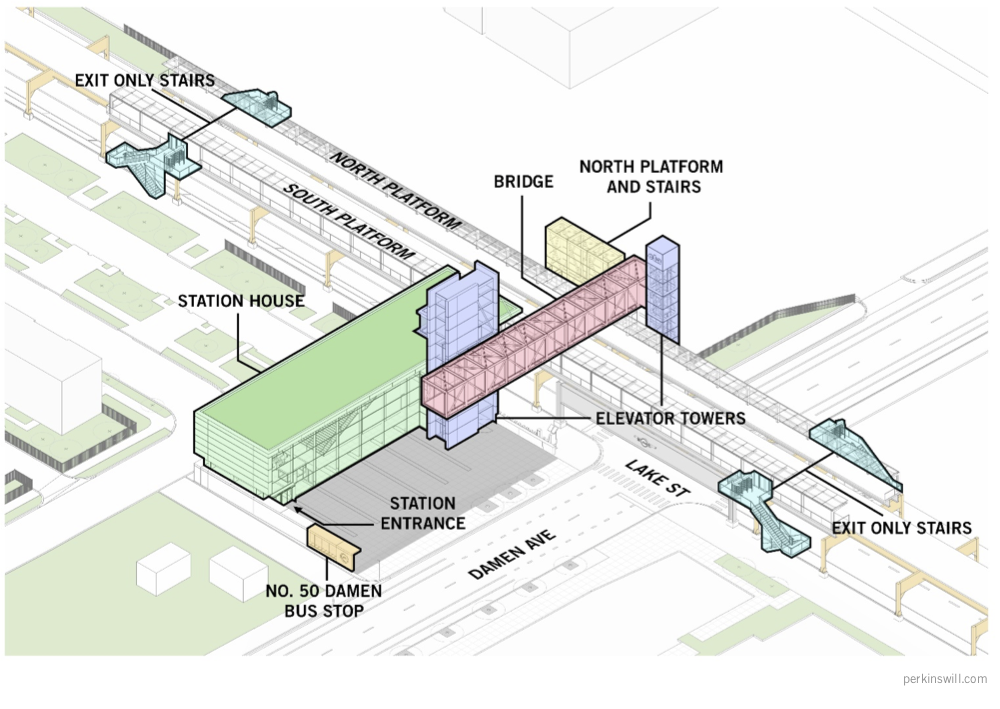

When I first saw the design for the new Green Line station at Damen Avenue on the Lake Street branch, I became worried that the station didn't have an entrance providing access to the westbound platform. Several of the other stations on the branch to city's West Side and Oak Park have entrances on both sides: Ashland, Morgan, and Conservatory-Central Park Drive, to name a few.

The Damen station is designed by the architecture firm Perkins & Will and the project is managed by the Chicago Department of Transportation for the CTA.

The lack of a westbound entrance, coupled with the low-intensity use of nearby city-owned land and other parcels, also raised a red flag that not enough was being done to prime the surrounding area to take advantage of the improved rapid transit access.

The station will have non-wheelchair-accessible exits at both ends of both platforms, in addition to the single entrance on the south side of the station. People traveling east only need to go up one level to the eastbound train platform, but those traveling west will need to ascend two levels to a bridge and the descend a level to the westbound platform. An elevator on the north side of the station will carry passengers between the bridge and westbound platform, but it won't go all the way to the ground.

CDOT spokesperson Mike Claffey told me that, due to Americans with Disabilities Act requirements, if a direct entrance to the westbound platform was provided, it would have to be wheelchair accessible, so it couldn't require customers to go through a Rotogate, the revolving-door-like device the agency normally uses at entrances that aren't monitored by a customer assistant. (The new Sunnyside entrance to the Wilson station in Uptown features a wheelchair gate with a high door to discourage fare evasion. The gate is within sight of a small office with a glass door, but the entrance doesn't have a dedicated attendant.)

A 12,300 square foot city-owned property is being used for the front entrance to the new Damen station. Claffey said that the plaza will have some landscaping, despite what the city's renderings show. According to the design, a Divvy station will be about 100 feet from the station entrance, behind a low wall.

Claffey said the station house and the area outside it are extra large to accommodate United Center crowds. He added that there are about 160 events at the stadium annually.

Current zoning on the station property would have allowed the city to incorporate 17 apartments in the station design. While including onsite housing, offices, and retail in transit stations is a common practice around the world, it's unusual among Chicago train stops. Clark & Lake station is the only modern elevated station that is integrated within an office and retail building. Some older neighborhood 'L' stations on the Red Line have first-floor retail.

Across from the station entrance is a CHA-owned property that's been vacant since at least 1988. A new residential building is planned here, and shown in the renderings.

To the south of the station area is a communications tower that occupies a corner of an otherwise vacant lot, with its own alley or driveway. This is a poor use of urban land.

Communications equipment owners often sign longterm leases, but given that nowadays most communications equipment is attached to buildings, there's an opportunity for the city to use eminent domain to purchase the land. The property owner or the city should redevelopment the land to take advantage of the fact that it will have excellent transit access, by building housing, workplaces, and/or retail.

In the surrounding blocks, the city's planning department says they're working on two programs to address land use changes that the new station could inspire. Department of Planning & Development spokesperson Peter Strazzabosco said their department is working on a "market analysis of commercial and residential properties to the south" and a Planned Manufacturing District review.

North of the station, between Lake Street and the alley south of Grand Avenue, all of the land is in the Kinzie Corridor PMD, which restricts changing the zoning to allow uses other than manufacturing and low-density commercial and warehousing. Since May the planning department has also been reviewing how the PMD could be modified. This could happen by reducing the size of the district or allowing some sections of it to be rezoned.

Last year, the department changed the PMDs around Goose Island to reduce the restrictions on office development in some areas and allow new residential in other areas. The department has no timeline for when the Kinzie PMD review will be completed and any recommended changes would be adopted.

Both the market analysis and the PMD review of "will help inform planning opportunities for nearby land and help maximize the station’s benefits for the community," Strazzabosco said. DPD last met with property owners in May to discuss the PMD and hasn't set a schedule for future meetings.

In the meantime, a three acre piece of land next to the new station is for sale. Because of the PMD, this land can currently only be used for low-intensity development. Since many of the kinds of uses present in PMDs don't rely on nearby transit to sustain them, the addition of the station will do little to increase the value of land within the district. The city can unlock new value once it allows new uses on the land. While neighborhoods benefit from a new station, ridership is also maximized by appropriate land uses.

The city's plans for the station area are focused on accommodating United Center attendees rather than building up a neighborhood village around the new transit amenity. Train stations increase value in a city, especially on the properties surrounding them. Chicago should capitalize on this phenomenon by making sure nearby land – both city-owned and not – is used in a way that captures that value.