[Streetsblog Chicago editor John Greenfield publishes a weekly transportation column in the Chicago Reader. We syndicate the column on Streetsblog Chicago after it comes out online.]

Thanks to Donald Trump, the funding outlook for the long awaited, $2.3 billion Red Line extension looks pretty bleak right now.

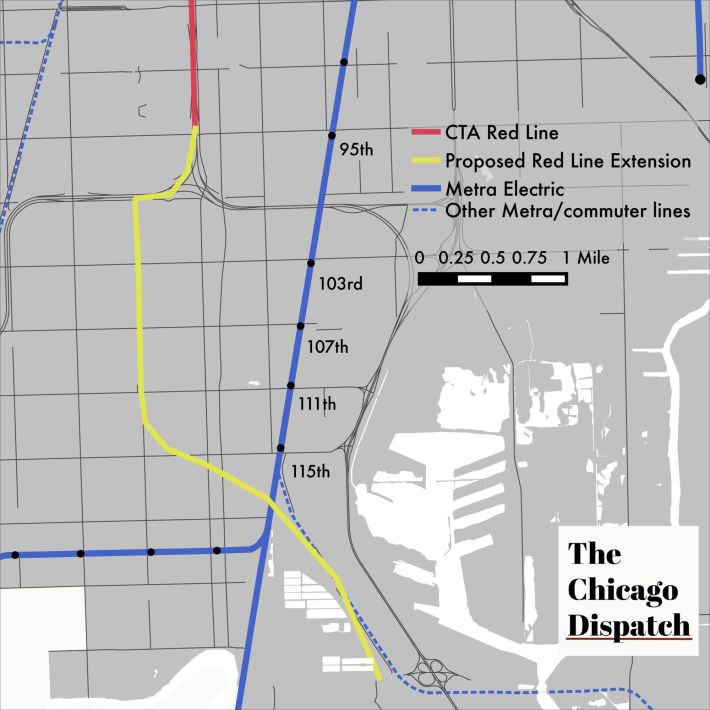

The proposal to lengthen the spine of Chicago’s el system from its current 95th Street terminus to the south end of the city has been talked about since the Nixon era, but in recent years the project picked up speed. On January 26 Mayor Rahm Emanuel announced the planned route, winding 5.3-miles across Roseland and Pullman to Altgeld Gardens, with stations proposed near 103rd, 111th, Michigan at 116th, and 130th streets.

At the time the CTA was hoping to apply to the Federal Transit Administration for upwards of $1 billion from its New Starts grant program, the main source of federal funding for public transportation expansion projects. But on February 11 when the Donald released the legislative outline for his much ballyhooed $1.5 trillion infrastructure bill, it was revealed that the plan called for only $200 billion in federal money for infrastructure – largely highway expansion – with the rest expected to come from local and state governments, plus private investments.

Moreover, much of that $200 billion would come from cuts to Amtrak and transit funding. To make matters worse, Trump’s 2019 budget proposal, released the same day, calls for slashing $3.7 billion from New Starts. It looks like it might be impossible to fund the extension until a Chicago-friendly Democrat is in the White House again.

But for decades transit experts and advocates have pointed to a much cheaper alternative for bringing rapid transit to the far south side. The Metra Electric District line runs more or less parallel to the Red Line and makes eight stops in the neighborhood that would be served by the extension. While the Electric Line runs only sporadically during nonrush hours, boosting its frequency to, say, every 15 minutes and integrating its fare system with the CTA would make it much more useful and affordable. And while the Red Line project breaks down to $434 million per mile, local policy analyst Daniel Kay Hertz has estimated that the Metra conversion would cost only $27 million a mile.

Even in a best-case scenario, construction of the new Red Line elevated tracks and stations – which would require purchasing some 150 properties -- wouldn’t begin until 2022, and service wouldn’t start until 2026. The Electric Line conversion, which would involve retrofitting existing infrastructure, could doubtless be accomplished much sooner.

Granted, a major advantage of the Red Line expansion over the Metra conversion would be the ability to take a one-seat ride from the far south side to any Red station on the north side. And a sticking point of the Electric Line scheme is that Metra and the CTA aren’t particularly good at collaborating. But, as Whet Moser discussed in a recent Chicago Magazine article, in light of the grim federal funding picture, recently transportation pundits like myself have noted that the Electric Line solution might still be the better approach.

However, it seems like this conversation has been missing some important voices: those of the residents who’d stand to gain the most from the new el service. Would they be willing to trade a longer Red Line for cheap, frequent Metra service if it meant getting the improvements sooner than later? To find out, I rode the el to 95th and traced the path of the proposed extension, buttonholing neighbors near the planned station locations.

From 95th the new tracks would run south along the Dan Ryan, and then bend west along the north side of I-57 for about half a mile. Near Eggleston Avenue the Red Line would head south along the west side of the Union Pacific Railroad corridor.

At 103rd and Eggleston I met Lelea Herring, a retired surgical technician who lives nearby. She regularly takes the 103rd Street bus to the Red Line, rides north to Roosevelt, and then takes another bus west to Damen to see her doctor on the Illinois Medical District campus.

Herring was somewhat familiar with the Red Line extension plan. “It’s convenient for me because it brings the train closer.” But when I told her that it wouldn’t be ready to ride until at least 2026 she wondered, “Oh Lord, will I even be here?” However, she noted that rapid transit service on the Electric line wouldn’t do her much good either since, the 103rd Street/Rosemoor Metra station is about the same distance from her home as the 95th Street terminal.

Around 108th the new Red Line route would cross to the east side of the Union Pacific tracks and continue south. Near the planned 111th station location I encountered Bruce Huskin, 58, who lives just south and does handyman work. While he’s enthusiastic about the possibility of having an el stop right by his house, he said inexpensive, frequent service on the Electric Line would also be useful for getting downtown, since he could ride a bus about a mile east to the 111th/Pullman Metra stop. “Whichever comes first, I’d be really excited for.”

After 111th, the Red Line would continue to hug the Union Pacific line as the railroad turns southeast and climbs an embankment to an overpass near 116th and Michigan. There I met Anthony Brown, 34, who lives near 115th and State and serves as a Safe Passages worker for Curtis Elementary, which is right by his home. He said his neighbors and coworkers are looking forward to getting a Red Line stop nearby.

“We’d kind of given up because we hadn’t heard anything for a while, but now the city is buying properties and asking questions,” Brown said. On February 13 the CTA held an open house about the extension at nearby Gwendolyn Brooks College Prep. “That’s something a lot of us are really happy to see.”

On the other hand, Brown said that if the Red Line extension wouldn’t open for another eight years or more, the Electric conversion would be a good consolation prize. It would still be fairly convenient for him since the 115th/Kensington station is about a ten-minute walk east from his house. And because the current Metra fare from that station to the Loop is $5.50, paying the $2.50 CTA fare instead would be a significant savings.

After Michigan, the Red Line extension would continue southeast, cross the Electric Line and join the South Shore Line corridor on its way to the future 130th Street station, located just northeast of Altgeld Gardens. Residents of that community would benefit greatly from the new el stop, since it would cut an estimated 20 minutes from their downtown commutes. The nearest Chicago Metra stop is at 121st and Michigan, about a ten-minute ride from the middle of the housing project via the #34 South Michigan bus.

At the point where the South Shore tracks pass under 130th, the street is a high-speed four-lane road with no sidewalks and little foot traffic, so I headed west a few blocks to Rosebud Farms grocery store to talk with locals. There I spoke with Sam McCarthy, 33, a construction worker who lives three miles northwest at 122nd and Elizabeth, right by the Electric Line’s Racine station.

Although the Metra solution would give him inexpensive, frequent train access, he favors the Red Line extension. “[The Electric conversion] would be a good idea too, but it wouldn’t create as many construction jobs.”

Obviously the pros and cons of the Red Line project and the Metra Electric conversion depend on where you live and where you need to go. But the latter definitely deserves further consideration. Far south siders shouldn’t have to wait until the Trump administration is just a bad memory before they get rapid transit service.