[Streetsblog Chicago editor John Greenfield publishes a weekly transportation column in the Chicago Reader. We syndicate the column on Streetsblog after it comes out online.]

Logan Square’s Illinois Centennial Monument, featuring an eagle-topped column and ringed by a hectic multilane traffic circle, is an icon of the rapidly gentrifying neighborhood. The pillar’s surrounding green space, also called Logan Square, is a popular site for relaxing on benches, sunbathing, and skateboarding. But in a community whose Latino population fell by about 36 percent between 2000 and 2014, according to the Census, while the number of whites grew by roughly 48 percent, the meaning of the monument depends on who you ask.

Latin United Community Housing Association director Juan Carlos Linares illustrated that point during a panel on preventing displacement, part of an equitable transit-oriented development symposium held downtown earlier this month. First he showed a photo of a Chase ATM screen with an image of two young white men with facial hair, coffee, and cruiser bikes lounging on the steps to the pillar. “This is what Chase wants us to see when we go to the Logan Square monument,” he said.

“But this is what you really see in Logan Square,” he said, showing a slide of the same location crowded with Latino mothers and children holding placards against local school funding cuts, a demonstration organized by the Logan Square Neighborhood Association. “Visuals matter.”

But one thing that many Logan Square residents agree on is that the layout of the traffic circle, along with the rest of the intersection, is a pain in the neck. Sitting in the six-way junction of Milwaukee, Kedzie, and Logan/Wrightwood, just southeast of the Blue Line’s Logan Square station, the circle requires people on foot to cross three or four traffic lanes to access the column.

Because walking from one side of the intersection to the other requires pedestrians to cross the street up to four times, the circle also discourages travel to and from the northern portion of the neighborhood. For better or for worse, this has slowed, but not stopped, the proliferation of new upscale retail and residential developments, common southeast of the monument.

The number of traffic lanes vary on different sides of the circle, and they don’t always line up, so it’s also a confusing, dangerous intersection for cyclists and motorists. There were 280 collisions within a 500-foot radius of the pillar between 2009 and 2014, including 62 injury crashes and one fatality, according to state crash data compiled by the Chicago Crash Browser.

At a Mayor’s Bicycle Advisory Council meeting on December 13, Chicago Department of Transportation staffers discussed plans to make the area around the monument safer and more accessible as part of a full makeover of the Milwaukee corridor from the circle to Belmont Avenue in Avondale.

This summer the department completed a $253,000 redesign of Milwaukee in Wicker Park and Bucktown, using street paint and plastic posts to do “quick-hit” improvements. The Logan-to-Belmont project is a more ambitious $10 million-plus initiative that will include more permanent safety fixes.

At the MBAC meeting CDOT planner Nathan Roseberry began a presentation on the upcoming initiative by discussing the history of the area around the monument and how it got to be so car-centric. “It’s been kinda fun really understanding what happened in this area,” he said.

El service to Logan Square started in 1895, with the line’s terminal located at the present-day site of First Midwest Bank and City Lit Books on the east side of Kedzie half a block south of Logan. When the column, designed by architect Henry Bacon with the eagle sculpted by Evelyn Longman (hence the name of the nearby gastropub Longman & Eagle), was installed in 1918 for Illinois’ 100th birthday, the green public square around it included a two-way road that crossed southwest to northeast across the green space from Kedzie to Milwaukee. This short street was replaced with green space within a decade.

In the Postwar period, the corners of the square were rounded off and the streets were widened, facilitating faster driving. And in the late 1960s a tunnel was dug under the square to accommodate the extension of the Blue Line to Jefferson Park, and the Logan Square station was moved to the northwest corner of the intersection.

Nowadays, Roseberry noted, the section of Milwaukee northwest of the monument is a very multimodal corridor. The sidewalks on this stretch see an average of 5,200 pedestrians a day, while bikes make up 4-7 percent of daily traffic, about 11 percent of inbound vehicles during the morning rush and outbound vehicles during the evening rush. And, as Chicago Magazine recently reported, an average of 4,137 people enter the Logan Square station every weekday.

CDOT held the first public hearing on the Milwaukee project in August, drawing 102 attendees, plus local aldermen Carlos Ramirez-Rosa and Scott Waguespack. Residents expressed an interest in providing more connectivity to the square, improving sidewalks and crosswalks, creating more useful public spaces, calming traffic and reducing congestion, adding more native plantings, trees, and seating, and preserving neighborhood identity and historic features.

At the MBAC meeting Roseberry said the department will present potential designs at another hearing this winter, and will unveil final plans at a meeting later in 2018. Construction could start in 2020.

Roseberry added that the improvements could involve new bike lanes, including “wraparound” lanes that would sit between the sidewalk and bus stop islands, reducing conflicts with buses. Bus service could be enhanced by consolidating stops, adding more shelters, and implementing transit-friendly stoplight technology and “queue jumps” that give buses a head start at intersections. People on foot would benefit from new sidewalk bump-outs, which would shorten crossing distances, and pedestrian islands. MBAC attendees were generally jazzed about these possibilities.

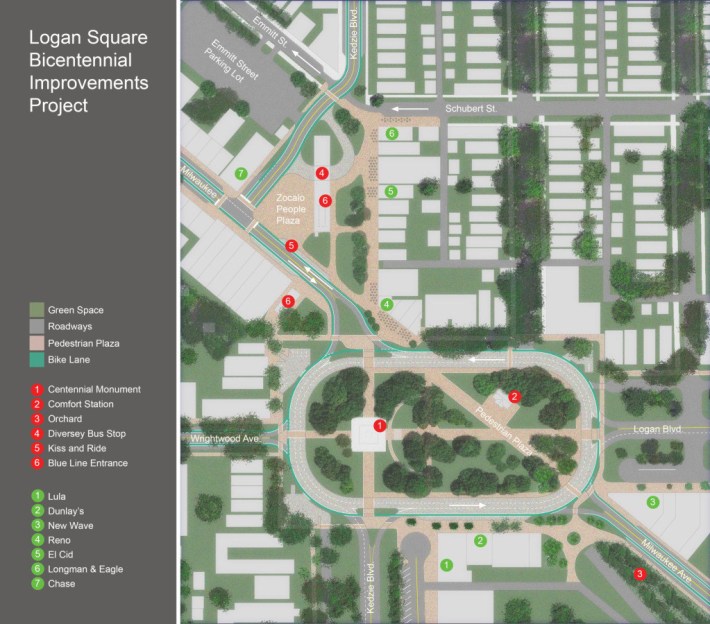

But the boldest ideas for remaking the square were first floated by Logan residents in a 2014 proposal called the Logan Square Bicentennial Improvements Project. This recommends pedestrianizing the segment of Milwaukee that crosses the square, which would connect the roughly triangular piece of parkland that houses the Comfort Station art space to the rest of the square. In this scenario, through traffic on Milwaukee would go around the square, rather than across it.

The proposal also calls for pedestrianizing a half block of Kedzie north of the monument, by Longman & Eagle, El Cid, and Logan Liquors, to create a new “Zocalo People Plaza.” Vehicles on Kedzie would be rerouted west of the Blue Line station. The proposal would create roughly two acres of new green space. Almost 500 people have signed an online petition in support.

“This kind of opportunity doesn’t come along often,” says Charlie Keel, a painting company owner who’s coordinating the bicentennial project. Fortunately, he says, city officials have been open to the residents’ forward-thinking ideas. “They understand that it’s not just about fixing Milwaukee now; it’s about doing something awesome and leaving a lasting legacy for our kids.”

CDOT spokesman Mike Claffey says the department is taking these outside-the-box ideas seriously. “Our next public meeting will show alternatives for consideration, which will include [new] public space as an element.”

Waguespack’s chief of staff, Paul Sajovec, says the alderman is excited about the proposal to create lively public spaces, similar to the vibrant plazas common in Latin America and Europe. “We want the square to function as the name suggests, rather than just a dead space surrounded by traffic. Not that it’s horrible right now, but we think the area has the potential to get several times more use.”

Ramirez-Rosa has introduced measures to regulate development in hopes of preventing displacement, including an ordinance that would downzone Milwaukee between Kimball and Central Park. This would require developers to get aldermanic approval for any project with more than one dwelling unit, like the upscale apartment towers that have been springing up farther southeast.

The alderman didn’t immediately respond to a request for comment on the Milwaukee initiative. But in September 2015 he told DNAinfo that he had asked Mayor Rahm Emanuel to support the Bicentennial Improvements Project, and Emanuel agreed to champion it. “I think it will be a [transformative] project on the scale of the Bloomingdale Trail,” Ramirez-Rosa said. However, since then the aldermen has been increasingly at loggerheads with the mayor -- this fall he posted a video on Facebook with a litany of grievances against Emanuel’s 2018 budget proposal.

LUCHA’s Linares said he wasn’t familiar enough with the project to comment, but suggested I contact Jaime Torres, owner of the social justice-focused architecture firm Canopy, located at 2864 N. Milwaukee. “There’s a great opportunity for more of a dynamic and civic experience around the traffic circle,” Torres says, adding that the Zocolo could benefit brick-and-mortar retail, as well as entrepreneurs like elote vendors. However, since boosting walkability will make the corridor more desirable to higher-end retail and development, he adds that the project needs to be a “really careful walk” that includes input from anti-displacement groups.

Closing streets to motorized traffic often draws a backlash, but hopefully CDOT, backed by political muscle from the aldermen and possibly the mayor, as well as community support, will move forward with the progressive recommendations from the Bicentennial Improvement Project. Safer streets and more green space would benefit residents from all walks of life.