Earlier this week, New York-based Transportation Alternatives released a statement of 10 principles that emerged from the Vision Zero symposium the group sponsored last Friday. It was the first-ever national gathering of thought leaders and advocates committed to spreading Vision Zero’s ethic of eliminating all traffic deaths through better design, enforcement, and education.

I caught up with Noah Budnick, deputy director of Transportation Alternatives, to hear more.

First, let’s talk about last Friday’s event. What was the best thing that happened there?

The momentum that was built was incredible. To me, that was the highlight. This was kind of the coming-out party for Vision Zero as a national movement.

What do you see as the goals of a national movement? Would that mean lots of cities working on this, or is there actually a role for the federal government? What could they do to promote Vision Zero?

The federal government could set federal goals and benchmarks in line with Vision Zero, creating policies that require states and cities and metro areas to set goals to eliminate traffic deaths and serious injuries. And it’s really important that that’s tied to funding.

It starts with a simple matter of leadership, which is stating that traffic deaths and serious injuries are preventable. They’re not accidents. That change in thinking is an incredibly important first step.

You put out a statement of principles yesterday. It’s actually more of a how-to, a 10-step Vision Zero user’s manual. How much of this has New York done? Have they hit every point?

[Reads over the list] Yeah, I’d say that New York has definitely started down the path on all of these. Honestly, when we drafted these, we were really focused on distilling the conversations that happened at the symposium. This came out of the day. The goal of the day was to have a real symposium, to have real working sessions that at the end produced a document that defines Vision Zero. I guess it’s a happy coincidence it also lines up very much with New York City’s work.

What do you think of all the new Vision Zero campaigns and public pledges that we’ve seen this year? Are there movements in other places that New York can learn from, or that are learning from New York?

Yes. New York is by no means beyond learning, and I heard from both advocates and government staff that were at the symposium that the conversations they had with folks around the country were really helpful.

Where are some of those other Vision Zero campaigns that you’re inspired by? That you feel are going to go far?

In both Washington and Chicago, the level of policy detail in the plans that came out of those city governments. In San Francisco, the broad coalition and engagement on Vision Zero is impressive. New York City did a lot of public outreach in terms of town hall meetings and hearings and online, but I think what they’ve done in San Francisco with the Vision Zero coalition is good work for us to note.

You know how people talk about BRT creep, where something starts off having all these great features and gets diluted and whittled away and compromised away until it’s nothing? I feel like there’s the risk of Vision Zero creep, where cities publicly take a Vision Zero pledge and pat themselves on the back for the really nice rhetoric and then they pick and choose from your list. Is that something you’ve seen? Is that something you worry about?

At the symposium, from the 300 people we had there from across the country that work at the local and national level, there was resounding agreement that the definition of Vision Zero is a time-bound goal of eliminating traffic deaths and serious injuries for all modes. One of the hopes that we had for the day was to define the brand. It was good that we were able to do that.

So you feel that however a city chooses to get there, as long as they take that pledge and say, “By this date, we’re going to be down to zero,” it’s all right with you.

Yeah. And that was a great thing to hear from Matts-Ake Belin from the Swedish Transport Administration. He said the way to get to Vision Zero is going to be a little different everywhere.

I worry that setting a target of zero as the only acceptable number sets cities up for failure and that in some places, public officials would want to take on a campaign like this -- they want to be part of this movement -- but they don’t want to have to come back and explain in 2025 or whatever year why they’re not at zero. Is that a fear you have in New York?

No. When the leadership acknowledges that all traffic deaths and serious injuries are preventable, then you can move past these policy debates about whether or not zero is appropriate, and you can start from a strong moral position.

But even if they’re all preventable it doesn’t necessarily mean they’re all preventable by the city.

That’s an important point that again comes from Matts: that this relies on the system designers. In transportation, that’s the government. It’s their responsibility to design streets. And it’s incumbent on the advocates to raise our standards for designing policies and designing streets.

But you have people driving cars into buildings; you have people driving cars onto curbs; you have people driving cars into roped-off public festivals at SXSW. That’s not a design issue.

That’s right, it isn’t. And the conversations on Friday went beyond design. There was a lot of talk about enforcement and culture, and an acknowledgement that culture change takes time. One of the quotes that was uttered over and over again was, “Culture eats policy for lunch.” Culture change happens in a lot of different ways, but it takes a while. But to me, culture change begins with leadership acknowledging that all traffic deaths and serious injuries are preventable, and then having accountability for safe design and safe behavior.

When I wrote something about Vision Zero recently, a lot of the comments were surprisingly critical of New York’s Vision Zero progress, that not enough is being done, that culture change isn’t happening, the city isn’t serious, the police department isn’t serious. What do you say to that?

What we wanted to do last week was check in on Mayor de Blasio’s commitment to Vision Zero and give the administration an opportunity to report on their progress, and we did.

Culture change is going to take time. But there are initiatives under way throughout the city government that show a true commitment from Mayor de Blasio to work on Vision Zero, and it’s only one year in. The first year was focused on getting the policies in place to make city safer, and now we’re looking at the implementation of those policies and the investment to build a safer city.

What’s next, not just in New York but nationally?

We’ll be doing a conference report this winter to capture more detail of what was discussed, and using that to continue to advance Vision Zero in New York City for year two. Nationally, I heard a lot of excitement about continuing to share best practices and to strengthen some sort of Vision Zero network.

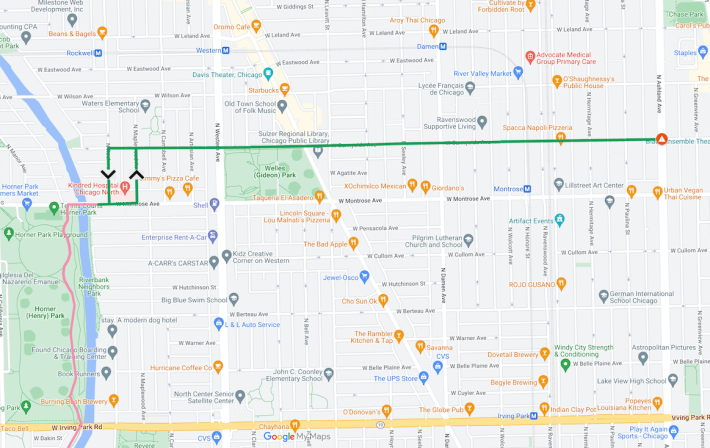

Also at the end of the day, as with a lot of things it comes down to money. In New York City, we’ll need investment from City Hall to rebuild the most dangerous streets. We heard from a lot of the big cities that there’s a small number of streets that account for the majority of fatalities and serious injuries. In New York City, 15 percent of streets account for over half of bicyclist and pedestrian injuries. For us at TA, that’s the first place we start. We need City Hall to invest in funding to transform those streets.