At least one Illinois legislator supports a unified transit agency, even though RTA board chairman John Gates and Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel have declared their opposition.

Senator Daniel Biss (D-9th, Evanston, Glenview) published a proposal [PDF] back in November, saying "the CTA, Metra, and Pace should combine into a single new Regional Transit Authority." That was months before Governor Quinn's transit task force issued a similar recommendation, due to be released in final form next week.

Biss's proposal calls for a streamlined RTA, with gubernatorial appointees who would need to be vetted by representatives from Chicago and its suburbs. While it leaves a few key questions unanswered -- namely, how long people would serve on the new agency's board, and how they could be removed from office -- the plan is a solid attempt at reforming regional transit governance without turning the new agency into the governor's plaything.

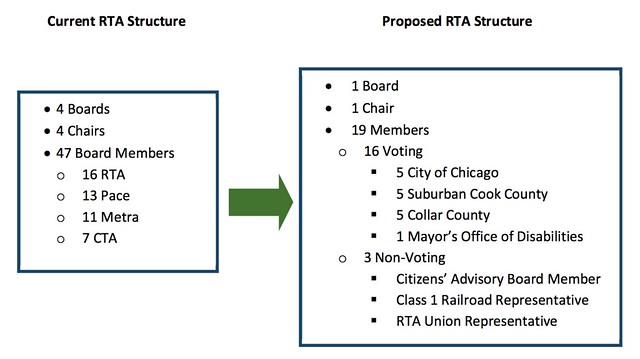

In the proposal, a new RTA with a 19-member board would replace the existing RTA board, three service boards, and their combined 47 members. The governor would appoint every board member, with the supermajority approval of a new Regional Transit Council -- made up of members appointed by the Chicago mayor, suburban Cook County commissioners, and board presidents from the collar counties (DuPage, Kane, Will, McHenry, and Lake).

The new RTA board would comprise five representatives from Chicago, five from suburban Cook County, five from the collar counties, and one representative from Chicago's Mayor's Office for People with Disabilities. New to Chicagoland transit boards would be three non-voting positions: a Citizens' Advisory Board member, a Metra operating railroads rep, and an RTA union rep.

While the task force recommended a unified transit agency with three service divisions, Biss outlines four: rapid transit (the 'L'), bus (both CTA and Pace services), paratransit (which Pace operates), and commuter rail (Metra). The RTA executive director would hire a manager for each transit division, to be approved by the board, and managers could only serve a maximum of two six-year terms. The RTA executive director could relieve division managers with board approval. It seems that Biss is creating a way to hire and fire that would have avoided the scandal surrounding the resignation of Alex Clifford, former Metra CEO. Each service division would have a board committee to recommend approval of its budget.

Biss recognizes the importance of working together for cohesive service planning and budgeting by involving the Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning, the region's federally-mandated planning organization, to help staff the fifth committee:

It makes sense to maintain a separation between the management of day-to-day operations of the different modes of transit, which is why each division should have its own committee. However, when it comes to long-term planning and prioritizing capital investments, it is absolutely crucial for the systems to be working strategically in concert. Therefore, a single capital budget committee should be responsible for approving each division’s annual capital budget.

The Biss proposal still leaves rail transit split between two silos, based on which railroad owned which tracks over a century ago. The task force's recommendations also keep transit services aligned by the current agencies, rather than by mode.

Chicagoland transit has a continuum of services: the Loop has a lot of 'L' stops and frequent service, as does the Metra Electric, while Metra's Heritage Corridor has few stops and infrequent service. Most of the rail transit system falls somewhere in between.

A single rail service division could take what are now called "commuter rail" services, like the Metra Electric, and give them higher frequencies appropriate to providing good access to job centers that have developed in the suburbs. Nothing would prevent a rail division from continuing to contract commuter rail operations to the freight railroads, but setting up a commuter rail-only division would likely ensure that Metra service continue as-is.

Other than the question of term lengths and how board members can be removed from office, Biss's proposal considers nearly everything in a transition from "RTA+3" to plain RTA. He describes how the RTA's administrative funding share would increase, and how funds now going to CTA, Metra, and Pace would be divvied among the new service divisions.

Biss doesn't stop at reorganizing the RTA in his proposal, though. He recognizes the mutual relationship of land use planning and private development in providing transit, where transit is the start of a positive feedback loop that results in greater economic activity.

Transit, working "hand in glove with public and private developers, land use policy, and economic activity... creates a 'virtuous cycle' where more development near transit nodes results in increased ridership." Consequently, increased ridership "bolsters the system's fiscal position and supports businesses near transit nodes." That leads to increased property values "in the transit shed," Biss says, and that stable tax base results in higher government revenues from which to reinvest in transit.

Additionally, Biss says any new state enterprise zones -- places where tax breaks are used to "stimulate growth in economically depressed areas" -- should be located near, and plan around, existing public infrastructure like transit. The Illinois Department of Transportation has a similar program that helps "businesses modernize state infrastructure serving their location," but it should be amended to "include elements of complete streets policies [that] would help incentivize businesses to develop walkable sites that are located near transit."

IDOT's involvement in regional planning comes into play as well. CMAP used to be funded by a "Comprehensive Regional Planning Fund" that was created by the state legislature but eliminated in 2010. IDOT now funds CMAP directly, but Biss calls for a new, dedicated fund to avoid leaving "CMAP too susceptible to IDOT's short-term pressures," as it has sometimes proven to be.

Biss's proposal claims that its structure "reflects the geographic priorities – and, yes, tensions – that currently dominate our transit discussions," ensuring that "these debates coexist with a unified planning process and a streamlined administration." Unlike the task force's draft proposals that could give the governor more power, the Biss proposal includes the level of detail that a thoughtful review of this subject requires. It's both optimistic that transit can flourish in Chicagoland, and confidently suggests a new structure that respects existing boundaries without being beholden to them.