When I worked at the Chicago Department of Transportation’s bicycle program, from 2001 to 2006, it was a very different department than it is today. While there was an interest in improving conditions for walking, transit, and cycling, the city’s main transportation goal, as it had been for most of the previous century, was to move cars. The most blatant example of this attitude during my time at CDOT was the 2005 removal of the pedestrian crossing between Buckingham Fountain and the lakefront to speed traffic on Lake Shore Drive.

Tom Kaeser, who worked at the department and its predecessors for 30 years before retiring from his post as assistant chief engineer in the division of traffic engineering in 2003, is a product of that cars-first era. I didn’t have many interactions with him at CDOT. But judging from a ten-page letter he sent to the CTA last month testifying against plans for bus rapid transit on Ashland, and Saturday’s Sun-Times article about his protest, he seems out of touch with the current approach at CDOT and other big city transportation departments.

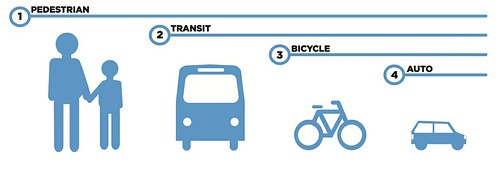

When Gabe Klein took over as commissioner in 2011, he shifted the focus from cars to people, implementing a wide range of projects, including pedestrian safety initiatives, bike-share, speed cameras, and the Bloomingdale Trail. The department committed to a new modal hierarchy in its 2013 Complete Streets Chicago design guideline, putting pedestrians first, then transit, then bikes, then cars. Under newly appointed commissioner Rebekah Scheinfeld, who helped spearhead BRT at her previous job at the CTA and started at CDOT in an interim capacity yesterday, it’s clear this progress will continue.

However, in his testimony against BRT, Kaeser displays the classic 20th Century traffic engineer’s mindset, where maintaining car traffic flow is more important than actually moving people efficiently through the city. “If the city ultimately decides to go ahead with bus rapid transit on Ashland, time will tell whether it truly lives up to the expectations of its enthusiastic supporters, or proves to be a dagger in the heart of Chicago,” he gloomily concludes at the end of his letter.

Kaeser told Sun-Times reporter Rosalind Rossi, who has given BRT consistently negative coverage, that ten times as many people currently travel Ashland in cars and trucks as buses. “You are giving half of the through traffic lanes and left turn lanes over to the buses for a very relatively lower proportion of users,” he said.

However, while the average annual daily traffic on Ashland ranges from 20,600 to 34,100 vehicles, there are about 31,000 boardings per day on the #9 Ashland bus, according to CTA spokeswoman Lambrini Lukidis. 71 percent of households along the corridor own one or no automobile, and only about half of work commutes are made by car, so he’s greatly underestimating the percentage of people currently traveling by bus. The CTA estimates that 14 percent of all current trips on Ashland are made by transit; after BRT the mode share is expected to nearly double to 26 percent, with 39,900 boardings per day.

Kaeser’s basic argument against Ashland BRT is that it would make driving less convenient, while he largely overlooks the fact that by slowing down car traffic and greatly increasing bus speeds and reliability, the result will be a major mode shift. He worries that because there will be fewer remaining mixed traffic lanes on Ashland than on BRT streets he looked at in other cities, and because Western is the only multilane north-south surface road nearby, the result will be gridlock and/or vehicles barreling down side streets.

In his letter, Kaeser criticizes the traffic modeling for the project, arguing that shifts in driver behavior won't be as large as predicted, leading to worse congestion. It's true that traffic modeling is more art than science, but fears of carmaggeddon rarely play out like that.

“The assumption is that traffic volumes are akin to water in pipes,” Ian Lockwood, a transportation engineer who specializes in smart growth and traffic-calming projects at the firm AECOM, told me for an earlier article. “The incompressible fluid has to go somewhere, so it follows that if lanes are removed motorists will use parallel neighborhood streets. However, in real life, I’ve only seen the opposite effect when the whole arterial corridor is made less automobile-oriented.”

Kaeser is fundamentally concerned about having sufficient space to move cars on Chicago streets, and that’s a worldview that destroys cities. His background as a city traffic engineer does make him an expert on expediting driving. But when you shape a city based on those concerns, roads get widened, neighborhoods get gutted, and you wind up with communities like Schaumburg, where it’s nearly impossible to go anywhere without an automobile.

The main counter to Kaeser’s logic is that after BRT is built, the street, and to some degree the city, will become less about cars and more about transit and walking. What Kaeser sees as a bug in the BRT plan, the relative narrowness of Ashland compared to other BRT streets he looked at, is in many ways an asset. It means that transit will be extremely time-competitive with driving and thus more appealing. Because Ashland isn't an eight-lane arterial road, it will be attractive for pedestrian-friendly development. If you're looking at the project from the worldview that good cities are walkable places where you can get around without a car, then many of the aspects of the plan he cites as negatives turn out to be positives.

Near the end of his letter, Kaeser compares Ashland to other multilane arterials like Western, 95th and Irving Park as an argument against reconfiguring the street. “These important roadways are not some sort of wide, underused streets with excess right-of-way sitting idle and available for use by earnest transit planners, but play a critical role in traffic circulation in the city,” he writes. However, the fact that streets like these are important travel corridors is exactly why they’re the right streets for rapid transit. BRT is going to shake things up and change how people get around. That’s the point of the project.