"...the transportation profession is coming to understand that more roads, more lanes, and longer signal cycles only induces more traffic."

You can find that statement on page 80 of the Complete Streets Design Guidelines [PDF] released yesterday by the Chicago Department of Transportation, which says loud and clear that designing streets to just move cars doesn't work. This new document is an indicator of the direction that Chicago is taking with its street design and transportation safety policies. It should help codify ideas to make streets work for walking, biking, and transit in both the transportation and zoning departments.

Chicago has had a complete streets policy since 2006, when Mayor Richard M. Daley created one through an executive order. The new guidelines mark the most notable effort to date by the Chicago Department of Transportation to instill the intentions of that policy in the work of its engineers, planners, and managers, while giving citizens a new tool through which to gauge the department's progress as streets undergo changes.

While the guidebook has a lot of diagrams, acronyms, and concepts that are intended for street engineers and planners, it is highly accessible to Chicagoans who don't have an advanced degree in transportation planning. And in addition to serving as an internal guide, the document shows property owners and builders exactly how they should design their developments before coming to city staff to propose them.

One of the first things Streetsblog readers should appreciate are the clear statements about how streets should operate in the future. Right off the bat, the Complete Streets Guidelines establish who planners should keep in mind first and foremost when designing streets:

To create complete streets, CDOT has adopted a pedestrian-first modal hierarchy. All transportation projects and programs, from scoping to maintenance, will favor pedestrians first. This paradigm will balance Chicago’s streets and make them more "complete."

As the executive summary goes on to say, "the prudent driver" still has a place in the hierarchy, but streets must optimize the movement of people, not vehicles, and that means more efficient modes take precedence over cars. And who is the prudent driver? People who drive slowly, safely, and respectfully. This is the driving behavior that fits into the city's new pedestrian-first modal hierarchy.

The document packages some concepts that CDOT has already implemented together with new standards for street design in Chicago. Here are a few highlights from the guidelines that show how street geometry and design will change:

Walking

An important safety imperative is embedded in the rule that "marked crosswalks should not be longer than three lanes." Streetsblog readers can likely identify dozens of locations around Chicago that need sidewalk extensions or pedestrian refuge islands to make the crosswalks comply with this rule.

To reduce the risk posed by drivers turning across sidewalks, the guidelines discuss the negative effects of driveways and curb cuts as well:

The number of driveways should also be minimized, as this will reduce conflict potential for all modes on the street or sidewalk. During project scoping, driveways should be surveyed and efforts made to consolidate or eliminate as many as possible. Utilizing an alley instead of a driveway for access is a recommended practice.

A "Pedestrian Street" designation can prevent the addition of curb cuts, but as we've seen, there are ways to circumvent it.

Driving

It's great to see CDOT acknowledge the danger of allowing drivers to turn on red:

Turns on red were implemented in the 1970s in a (questionable) effort to save fuel. Turns on red adversely impact pedestrian comfort and safety.

What will change now? The document lists when and where right-turn-on-red should be restricted, including along pedestrian and bicycle priority streets, within 300 feet of libraries, senior centers, and train stations, in safety zones, and in the Loop and River North.

Trucks and large vehicles

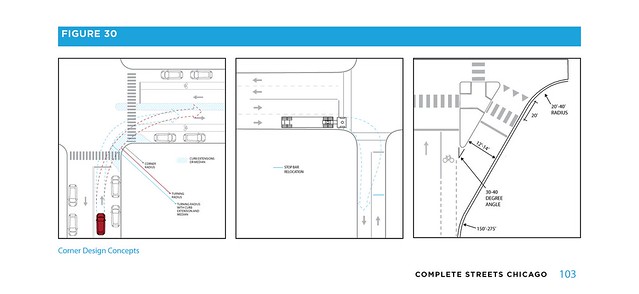

Engineers often design street corners for wide turns to accommodate the movement of big trucks and other large vehicles, like fire engines. This has a terrible effect on pedestrian safety by encouraging all drivers to speed around corners and lengthening crossing distances. The guidelines say that to accommodate semi-trucks, a large turning radius isn't the way to do it. Instead, since truck drivers will make many right turns not from the curb lane, but from a middle lane, and turn into another middle lane to avoid running over the curb (even if it has a large radius), the street corner can be more of a sharp angle. To accommodate truck turns, advance stop bars on the street that trucks turn onto can keep other vehicles in the oncoming lane out of the way. The first and second panes below show this best:

Room for improvement

The Complete Streets Design Guidelines have at least one inconsistency with the Pedestrian Plan CDOT released last September. The Pedestrian Plan calls for the removal of "channelized right turn lanes" (see the third pane of the diagram above for an example), which decrease pedestrian safety. But the new guidelines, which refer to this treatment as "slip lanes," give the impression that new slip lanes are in fact allowed, even if they are "not encouraged."

Rush hour parking controls, which put moving traffic right next to the sidewalk during morning and evening commute times, aren't dealt with in detail. The only mention is an acknowledgment that "streets designed for rush hour volumes end up with excess speed and width off- peak and at night." CDOT does recognize how rush hour parking controls degrade the pedestrian environment, and, as Streetsblog has pointed out, they also prevent the installation of bike lanes, so it would be good to see them get more thorough consideration in the guidelines.

The document is light on bike treatments, deferring to the CDOT Bicycle Program when discussing the location and design of bikeways. However, it's unclear what documents or guidelines the Bicycle Program is using. The National Association of City Transportation Officials Urban Bikeway Design Guide is known to be a reference for the department, but it would help to see some explicit reference to where Chicago's bikeway designs come from.

What's next?

It would be great to put this document in the hands of local school councils, neighborhood groups, and aldermen so Chicagoans can effectively advocate for retrofitting streets to function like the examples so eloquently described and diagrammed in the Chicago Complete Streets Design Guidelines.