Read the University of Illinois Champaign-Urban's News Bureau's writeup here.

Check out an abstract for the article, and access and purchase options here.

It took me a while to come around to embracing the rise of electric scooter use, but in recent years I've come around to seeing the upsides of the mode. The gadgets provide an alternative to automobile use for people who aren't interested in exercising and/or risking getting sweaty during a commute. Fewer cars on the street means less danger to other road users, pollution, and congestion.

And many "scooteristas" are, understandably, unwilling to share the road with fast drivers. That creates a larger constituency for installing protected lanes on main streets, and Neighborhood Greenways on residential roads. That in turn encourages all sustainable transportation device users to ride in the street, not on sidewalks, making conditions safer for people on foot.

"Why is Chicago building protected bike lanes? Nobody rides in them 6 months a year when it's cold here."Here's what we saw in the downtown Dearborn Street PBLs during a 4-minute bike ride on Wednesday 12/10 around 4 PM (not peak rush hour), when it was about 32F.

— Streetsblog Chicago (@chi.streetsblog.org) 2025-12-14T16:31:48.635Z

Despite chilly temperatures, both bicycle riders and scooteristas were using the Dearborn Street protected bike lane in the Loop last week, which helps justify its existence.

So I was was troubled when I recently heard about a new study from University of Illinois researchers that argued e-scooters actually have major downsides in terms of increasing car use and lawbreaking.

The University of Illinois Champaign-Urban's News Bureau reported earlier this fall, "The introduction of shared e-scooters in Chicago boosted demand for [ride-hail] services but reduced bike-share usage — and was also linked with higher rates of street and vehicle-related crime in neighborhoods, says new research co-authored by Unnati Narang, a professor of business administration at the Gies College of Business." The project was a collaboration with Ruichun Liu of San José State University, a former Illinois graduate student.

That statement rang "Correlation does necessarily not equal causation" alarm bells in my head, so I reached out to Narang for more info on their methodology. In the following section, I'll walk through excerpts from the News Bureau's article (in quotes) followed by the questions I emailed Narang about the study (in bold), followed by passages from her written responses (in italics). After that, I'll share some responses to the U. of I. findings from a local transportation expert; one of Chicago's e-scooter concessionaires; and a mobility justice advocate.

Q & A with Narang

News Bureau: "A new study from a University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign marketing expert finds that electric scooters, one of the fastest-growing forms of urban transportation, reshape city mobility in unexpected ways."

John Greenfield: Do you use rental e-scooters or bike-share, or ride a personal e-scooter or bicycle, on a regular basis yourself?

Unnati Narang: “I am actually quite nervous to ride [e-scooters] because of the speed! But I do use them at U. of I. campus to get around. I noticed that my dad, who is over 70 years old, was much more graceful and natural when it came to riding e-scooters. My co-author is also good at using them!”

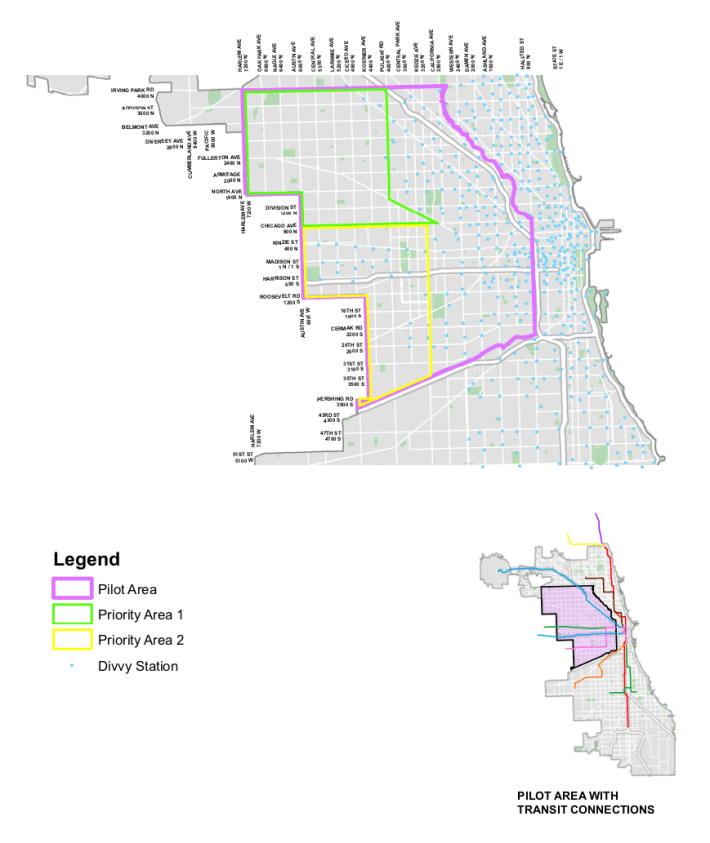

NB: "The researchers analyzed the introduction of e-scooters in Chicago during the summer of 2019, when the City allowed ten companies to deploy e-scooter rentals across a 50-square-mile area on the West and Northwest sides of the city.

Using data from more than eight million [ride-hail] trips, 750,000 bike-share rides and detailed crime reports across 866 census tracts, they applied a statistical method known as 'generalized synthetic control' to measure how e-scooter access changed travel and crime patterns compared to similar neighborhoods without them."

JG: What is "generalized synthetic control"?

UN: Generalized synthetic control belongs to a class of methods that allow us to construct a counterfactual or control group that serves as a baseline for comparison against treatment groups to infer causal effects.

NB: "While e-scooters expanded mobility and generated new economic activity, they also coincided with a 17.9 percent rise in reported crimes, concentrated in street and vehicle-related offenses such as car break-ins and thefts.

Their analysis covered 41 weeks of data, capturing both pre- and post-rollout trends in mobility and safety.

E-scooter availability led to a 15.7 percent increase in short [ride-hail] trips, but bike-share programs saw a 7.6 percent decline in trips in areas with scooter access, suggesting that riders often substituted e-scooters for rental bikes.

'The increased rideshare trips from e-scooters reflects what we call a category expansion effect,' said Narang, the John M. Jones Fellow of Marketing and Deloitte Scholar. 'E-scooters encourage people to take trips they might not have otherwise made, often combining trips with [ride-hail]. For example, riding an e-scooter to dinner, then calling a [ride-hail] vehicle to get home. Or going to the grocery store but needing a ride back with grocery bags. '"

JG: Did you do any research on how the new e-scooters correlated with transit use? One would guess that the availability of e-scooters would make train transit, such as the Chicago ‘L’ or Metra commuter rail, more appealing, since e-scooters are a fast, relatively cheap alternative to walking, buses, and ride-hail for "first- and last-mile trips" to and from stations.

UN: In some of the earlier versions of the paper, we had examined public transportation outcomes. Due to data limitations, we could mainly examine taxi use – that showed similar increases as rideshare. Ultimately, the paper was focused more on shared services than public transport to speak more to the sharing economy context and cross-platform effects.

JG: Do you have data for the total number of "shared-mobility device" trips before and after the e-scooters were introduced? It’s understandable that the new scooters would make some people choose scooters over bike-share. But was it the case that the total number of scooter-share plus bike-share trips, i.e. shared-mobility device trips, increased after the scooters were introduced?

UN: The total number of [shared-mobility device] trips indeed [increased] from our 2019 time period pre- vs. post-e-scooter launch. So we see overall expansion of shared-mobility device trips like you said.

(In the News Bureau piece, Nagrang is quoted as saying, "E-scooters are hailed as an environment-friendly innovation... but their impact goes beyond what we know in the marketing literature... They accrue... environmental costs." However, she just acknowledged to Streetsblog that, while the introduction of e-scooters correlated with less bike-share use, it also correlated with more total shared-mobility device trips. That might have actually represented an overall environmental benefit, as opposed to a cost.)

NB: "The researchers emphasized that this [17.9 percent increase in crime that correlated with the introduction of scooters] represents a hidden social cost that cities should consider when evaluating urban transportation policies.

JG: This obviously raises “correlation is not causation” questions. While the introduction of e-scooters "coincided" with a crime spike in these neighborhoods, what evidence do you have that the e-scooters caused the crime increase?

UN: In our research design, we infer causal effects through the synthetic control approach. This approach allows us to create counterfactual control groups (i.e., areas without e-scooter introduction) that mirror the treatment group (i.e., areas with e-scooter introduction) closely and observe changes over time in the treatment group relative to changes over time. This allows for the idea that crime could be increasing in both areas overall over time, but that it increases relatively more in the treatment areas with e-scooters.

JG: For example did you research whether any of these neighborhoods had gang conflicts at the time that may have contributed to more crime? Did you check if there was a closing of a major employer that may have led more people to turn to theft in these areas?

UN: Since we compare treated (with e-scooters) and control counterfactual (similar areas without e-scooters) groups, the idea is that on average the neighborhoods we compare will be similar in other features including presence of gang conflict or closure of large establishments pre- launch.

(Just because these neighborhoods are similar, that doesn't rule out the possibility that, as it happened, more scooter communities experienced things like gang conflicts and/or employer closings than non-scooter communities. Therefore, it could still be the case that the scooters weren't to blame for the crime increases.)

JG: Is it possible some of the new crimes were simply people stealing the new e-scooters?

UN: Within the limits of our study, we can conclude that street and vehicle related crimes increase. We do not know whether these entail theft of e-scooters, although based on news reports from many parts of the U.S. (e.g., California), this is likely.

(So, yes, the increase in crime in scooter neighborhoods may have been partly due to there being new objects on the street to steal.)

JG: You can understand why this is a very important issue. If you say things like, "This rise in crime represents a hidden social cost [of e-scooters]" or "E-scooters are portable and fast, which makes them attractive tools for crimes of opportunity," without providing actual evidence that’s the case, you’re encouraging communities to reject scooters, even though they may have overall societal benefits.

UN: There are both pros and cons – indeed mobility access and commute opportunities increase, but they also lead to more [ride-hail] use, less bike-share use [again, Narang admitted to not knowing whether e-scooters lead to more transit use, and acknowledged that they do lead to more total shared-mobility device use] and more crime [again, they didn't really prove that]. "Overall societal benefits" is important to capture like you said – and needs a collective set of studies and not one study in isolation, to truly document it.

NB: "Policymakers often see e-scooters as a green alternative, but because they increase short [ride-hail] trips rather than substituting for them, their net environmental effect is negative," Narang said. "In fact, we found that although rented e-scooters contributed about $8.1 million in ridesharing revenues, they also had an unintended negative environmental effect amounting to over 800 metric tons of carbon emissions per year."

(Again, the study does not take into account how many private car trips were replaced by e-scooter journeys, so it makes no sense for the researchers to estimate the total impact on carbon emissions.)

JG: What evidence do you have that e-scooter trips were responsible for more short-term ride-hail trips? I understand your theory of why that might happen. But do you have any actual evidence that e-scooter trips were to blame for these short ride-hail trips?

For example, did you observe a correlation between the locations where e-scooter trips ended (say a restaurant or bar) and where ride-hail trips began?

UN: Indeed, we do this exact trip level analysis. We match e-scooter start and end points (using lat long data on trip coordinates) to ride-hail end and start points. In the paper, we have a figure that shows complementarities especially for [ride-hail] being used as a complement to e-scooters.

(That seems like compelling evidence that people combined e-scooter and ride-hail trips. On the other hand, if that practice replaced a significant number of two-way private car or ride-hail trips, that could be a feature, rather a defect, of the scooter program.)

Response to the study from DePaul University transportation expert Joe Schwieterman

"The study's scope is impressive, but I suspect there are confounding factors that make the link from e-scooters to crime spurious," Scwieterman said. "It is very difficult to control the factors that may explain crime rates. The findings that e-scooters have such a large negative effect, while plausible, needs to be taken with a grain of salt."

"The study raises important questions about carbon emissions," Schwieterman added. "It is hard to know the effects of rising e-scooter traffic on emissions. Without abundant shared e-scooters, more people may be living in auto-centric areas, greatly elevating CO2 levels. Some people might otherwise ask family or friends to drive them to their destination is in their cars, a shift that would be hard to quantify."

"A notable aspect of the study is the rich data set and willing to challenge us about shared mobility," Schwieterman concluded. "A key question lurking in the background is whether e-scooters will, in the long run, reduce car ownership. That is hard to measure in these swirling post-pandemic times, when there are so many divergent factors – including ever-changing work-from-home policies but I suspect the answer is 'yes.'"

Response from Lime, one of Chicago's e-scooter concessionaires

"We have concerns about the methodology of this study, which draws broad conclusions from a limited data set in 2019 and does not sufficiently connect correlation of increases in select crime statistics with causation," said Lime enior Director, Government + Community Relations Lee Foley. "This is not a phenomenon we have seen over our six-plus years in Chicago, nor in the many cities we serve around the world."

"As it relates to emissions, studies conducted more recently than 2019 have consistently found that micromobility reduces overall carbon emissions from city transportation networks, rendering the findings of the study in this area either obsolete, or at least, inconclusive," Foley added. "This 2022 Fraunhofer ISI study, based on modal shift and a full service life cycle analysis found more conclusively that programs operated by Lime in six cities around the world led to decreases in overall emissions from transportation."

"Lime's service to Chicgao is based around equity," Foley asserted. "To take claims that providing more transportation options disproportionately harms historically underserved communities at face value allows significant assumptions to go unchallenged, especially given that this report completely fails to acknowledge that through our discounted pricing program, Lime Access and our geography-based discounts which are cornerstones of our service and equity commitment in Chicago, hundreds of thousands of riders move more freely within their city. Since launching in Chicago, our riders have taken over 11 million total rides, with 4 million of those going to Lime Access riders and Equity Priority Area riders as of August 2025."

Response from the mobility justice nonprofit Equiticity

"Generations of segregation and disinvestment have left racially marginalized communities in Chicago adversely impacted by violence, health disparities, unemployment, poverty, over-policing and constrained mobility," said Equiticity founder and CEO Oboi Reid. "As the Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning stated, “Transportation can play a key role in creating pathways to opportunity for low-income communities [and] people of color."

"This research does not make clear the causal connection between increased scooter-share and increased crime," Reed added. "Now is not the time to retreat from scooters as an important contribution, in addition to bike-share, to increasing mobility for marginalized people. Now is the time to double down on shared mobility and innovate around active transportation, with neighborhood residents and community-based organizations leading the work in partnership with the City of Chicago and other government agencies in the region."

"We must all work to ensure all modes of travel are present and equitable in our neighborhoods," Reid concluded. "This includes scooters, bike-share, transit, walking, cycling, and other shared mobility. I am confident vibrant active transportation combined with social infrastructure will contribute to reducing crime and violence in our communities."

Read the University of Illinois Champaign-Urban's News Bureau's writeup here.

Check out an abstract for the article, and access and purchase options here.

On November 12, SBC launched our 2026 fund drive to raise $50K through ad sales and donations. That will complete next year's budget, at a time when it's tough to find grant money. Big thanks to all the readers who have chipped in so far to help keep this site rolling all next year! Currently, we're at $6,370, with $43,630 to go, ideally by the end of February.

If you value our livable streets reporting and advocacy, please consider making a tax-exempt end-of-year gift here. If you can afford a contribution of $100 or more, think of it as a subscription. That will help keep the site paywall-free for people on tighter budgets, as well as decision-makers. Thanks for your support!

– John Greenfield, editor