John Norquist previously served as the mayor of Milwaukee and president of Congress for the New Urbanism, a nonprofit that promotes ideas for making cities more people-friendly. A longtime advocate of freeway removal, yesterday, he took a stroll in Chicago's downtown River North neighborhood and West Town community to assess the notorious Ohio Street (600 N.) feeder ramp.

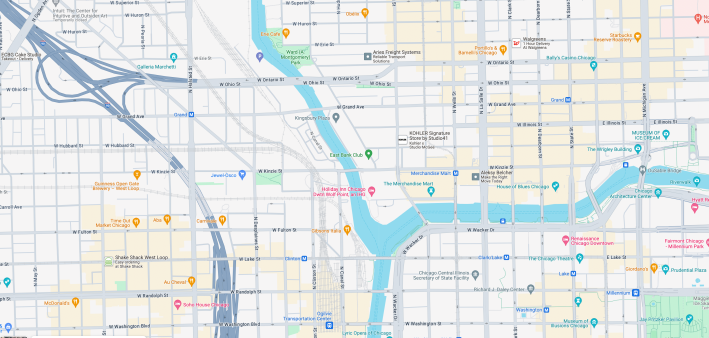

The freeway extension runs between north-south Orleans Street (330 W.) in River North and a West Town interchange with the Kennedy Expressway, which runs between the West Loop and O'Hare Airport. Joining him were a couple of former colleagues, CNU board member Gary Scott and urban designer Alex McKeag.

"Instead of looking at the map, we looked in person, and saw that the freeway ramp has suppressed development opportunities on the northwest side of downtown," said Norquist. He currently lives in Chicago's Rogers Park neighborhood on the Far North Side.

Norquistargued that swapping the expressway extension for a surface-level boulevard would be an obvious choice to make this part of town safer, more efficient, more environmentally friendly, more vibrant – and more profitable. "Instead of making it harder to get to River North from the Kennedy, it would expand River North closer to the Kennedy."

Norquist led the City of Milwaukee between May 1988 and January 2004, when he left the position to work at CNU. He said that prior to becoming the mayor of Cream City, he was part of that city's 1970s "anti-freeway resistance movement" that helped put the brakes on several destructive highway proposals. "We elected anti-freeway legislators, and by 1979 there was no one left in Milwaukee's delegation in the Wisconsin state legislature who supported highway expansion."

As mayor, one of his most famous accomplishments was demolishing and repurposing the Park East Freeway, which ran a little under one mile, just north of downtown Milwaukee, in 2003. Recently he's spoken out against Wisconsin Governor Tony Evers' plan to add lanes to three miles of I-94 west of downtown Cream City. He's also currently helping out with efforts to eliminate Buffalo's lightly used Kensington Expressway as an alternative to capping it, which would cost roughly a billion dollars.

As for the idea of tearing down the Ohio Feeder, a popular way for folks from the Chicago suburbs to access River North restaurants and nightlife, "Suburbanites will hate it," Norquist acknowledged. "But if you don't propose it, it's never going to happen."

He noted that when the removal of the Park East Freeway was pitched, "People originally said, 'You're mad. You're crazy. How are we going to get downtown?' But nowadays no one is complaining about it having been removed."

But wouldn't River North merchants be outraged by a proposal to eliminate the an expressway extension that leads to their businesses? Norquist noted that freeway removals have proven successful in cities ranging from Seoul to Paris to San Francisco. "Freeways don't work in cities."

SF actually saw travel times shorten when the Embarcadero Freeway was removed after being damaged by an earthquake, Norquist noted. "At rush hour, a boulevard carries more traffic because drivers move at the optimal speed. More and more research is piling up about the harmful aspects of urban freeways, including sprawl, pollution, congestion, and increased travel times. And you can't build a coffee shop on a freeway."

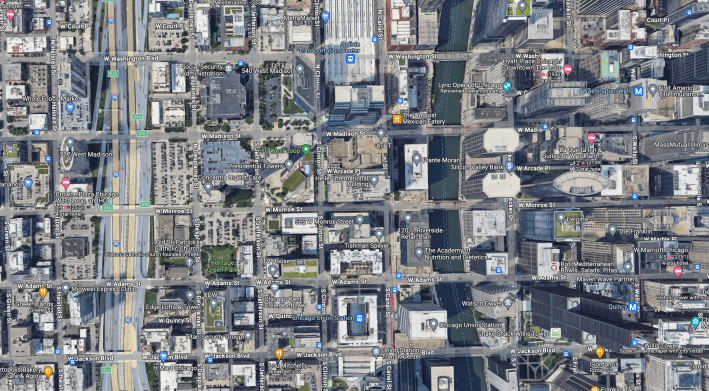

As for how Kennedy Expressway travelers would be able to get to River North without the Ohio Feeder, Norquist said, "Look at the access ramps for the Kennedy in the West Loop, like Jackson Boulevard [300 S.], Adams Street [200 S.], and Monroe Street [100 S.] The ramps run right alongside the expressway, and they immediately connect you with an urban street. People are able to get from the Dan Ryan to the Sears Tower without using a freeway."

Meanwhile, River North and West Town have far less development than they otherwise would because so much land is wasted by the Ohio Feeder and its Kennedy interchange, Norquist argued.

"It would take persistence like the Park East Freeway, where eventually the property owners saw the benefits," he said. "If you took down the Ohio Feeder, the first option would be to rebuild the pre-1960s urban grid. It would be a chance to help solve Chicago's housing crisis."

But wouldn't the owners of River North establishments like Harry Caray's restaurant at Dearborn (30 W.) and Kinzie (400 N.) streets throw a fit? They've recently been trying to stop the car-free dining district on Clark Street (100 W.) from returning this year, arguing that it makes it hard for drivers to access their businesses.

"Not every last person will be converted," Norquist conceded. "They have a right to be against it. But times change, and having a freeway running to your restaurant isn't necessarily going to appeal to the younger generation that drives less."

Transforming the Ohio Feeder into surface road, similar to what was done with Milwaukee's Park East Freeway "really won't require a change on every part of it," Norquist he said. "The bridge over the Chicago River was built in 1962 and fixed up in 1992. It's going be due for a rehab soon anyway. And it's not like you have to teat the whole freeway down. Much of it is practically at-grade, so you could turn it into a boulevard pretty easily."

"We really enjoyed yesterday's walk," Norquist concluded. "It was a chance to look at everything with fresh eyes, so I'd suggest other people give it a try."

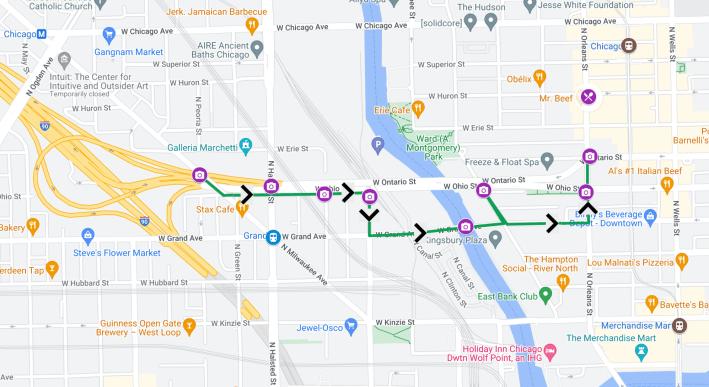

Streetsblog Chicago put together the above map of Norquist, Scott, and McKeag's roughly one-mile route for walking or biking. (Please note that not all the streets are bike-friendly, so this route is best for so-called "Enthused and Confident" riders.) Click here for an interactive version.

Did you appreciate this post? Please consider making a tax-deductible donation.