The renderings shown here, and therefore this post, mostly focus on how the lakefront beaches and parks could be expanded and bike/pedestrian access to the shoreline could be improved. In all of the renderings, DLSD retains the same eight-lane footprint it has now, still forming a huge barrier between neighborhoods and the lake, although some of the renderings show two of the mixed-traffic lanes converted to dedicated bus lanes. Some transportation advocates have proposed to transforming the drive into a smaller, multimodal, people-friendly surface boulevard. - Ed.

Each year, climate change knocks a little louder at Chicago’s door. Lake Michigan, its boundary pushed steadily eastward over the years—Grant Park, Streeterville, North Avenue beach and many more of the city’s prime lakefront real estate sit atop man-made “lakefill”—has increasingly made its presence and power felt. High water levels and historically severe storms now batter the shoreline and flood roads and buildings seasonally, especially DuSable Lake Shore Drive and the Lakefront Trail.

Concerns for the longevity of the lakefront, safety of road users, and sorely needed repairs to bridges and tunnels of the nearly 100-year-old DLSD are influencing Redefine the Drive, a plan that renderings reveal is on a near-Burnham scale. Redefine the Drive will rebuild the eight-mile stretch of North DuSable Lake Shore Drive from Grand Avenue to its terminus at Hollywood Avenue.

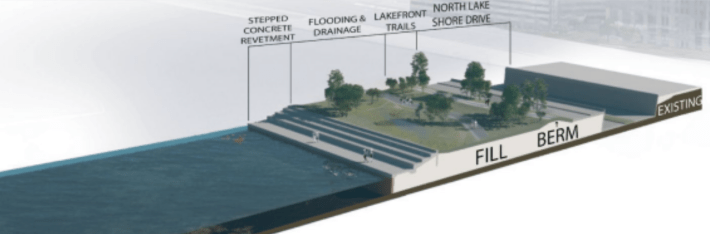

As part of the planning process, The project study group, comprised of the Chicago and Illinois transportation departments and the Chicago Park District, used computer and physical simulations (including a 1/50th scale wave basin) to model how different shoreline protections like new and higher concrete revetment walls, expanded beaches and offshore breakwaters would hold up against rising water levels and worsening storms.

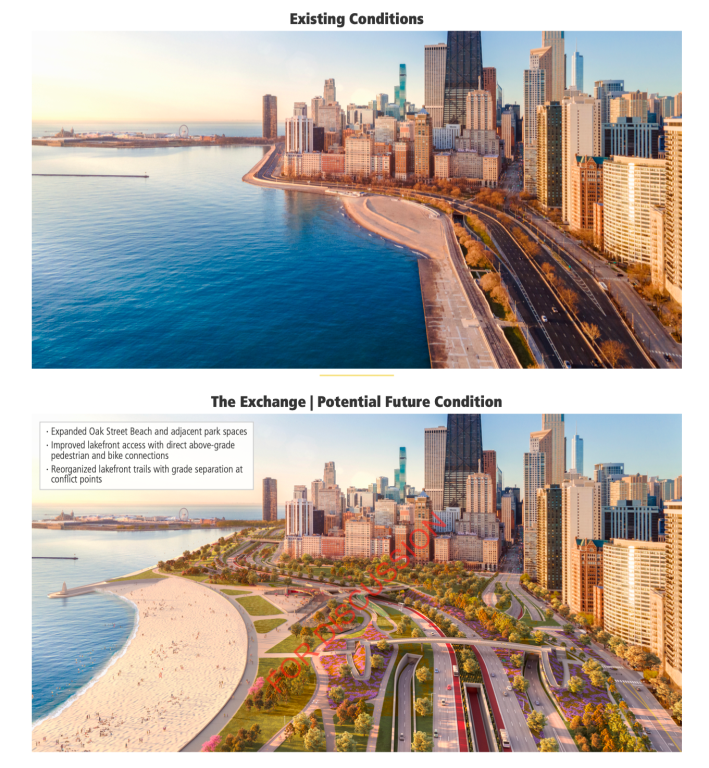

Drawings of potential changes were posted on the Redefine the Drive website, many which are various views of a dramatically transformed Oak Street beach and new green space running directly south past Chicago Avenue. The visualizations show a wider shoreline that creates beach and park buffers between breaking waves and DSLD and the Lakefront Trail.

The most arresting image tops the list, a before-and-after overhead view of Oak Street beach from the North.

The existing “concrete beach” north of the sandy Oak Street beach is replaced by park, through which separated bike and walking trails wind. The tiny oval of Oak Street beach moves east, making way for a large concession area, and expands dramatically both in depth and length, extending north to join with North Avenue beach. A rendering from the view at the top of the Hancock building, shown at the top of this post, illustrates how the stretch of shoreline from Oak Street to North Avenue—currently a thin concrete band that serves as both bike and walking path, vulnerable to crashing waves—blossoms into a green and sandy destination.

The new and improved beach would be accessible by two pedestrian and bicycle bridges—a huge improvement from the current narrow, dank underpasses that connect city streets to the lakefront.

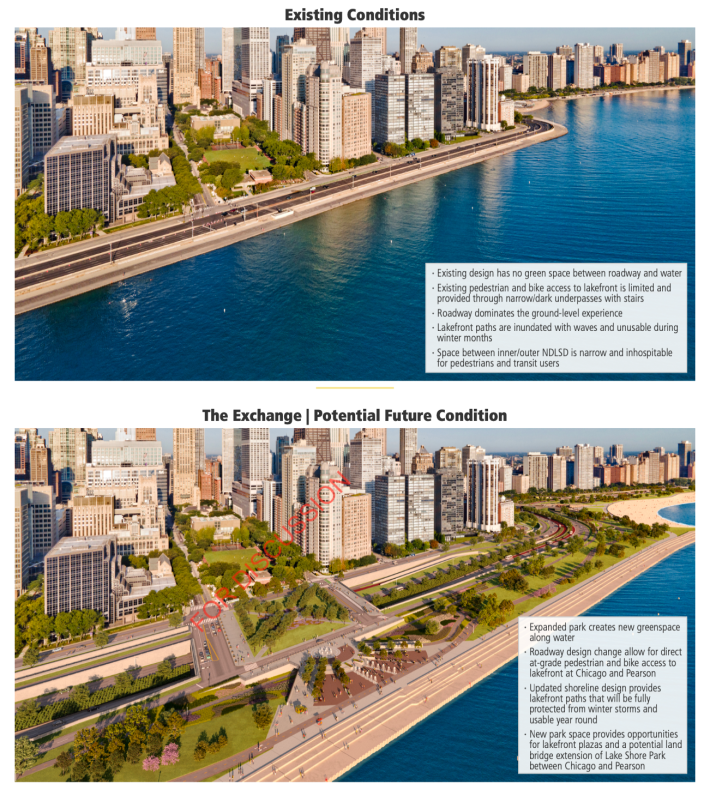

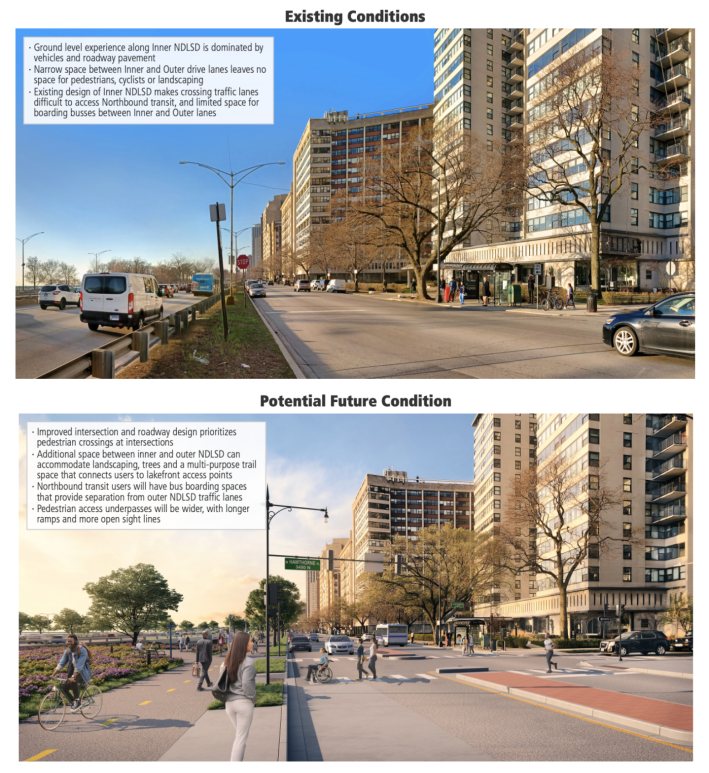

Moving inland, a view from Banks Street (1330 N.) shows how the additional land would provide breathing room between the Outer and Inner Drives. Outer DSLD would shift slightly east, creating space for pedestrian islands down the center of the Inner Drive and a smidge more room for transit riders awaiting northbound buses. The drawing also shows a bike/ped trail abutting the bus stop to the east—certainly a safer situation than the current fence narrowly separating people on foot from fast-moving traffic on the Outer Drive.

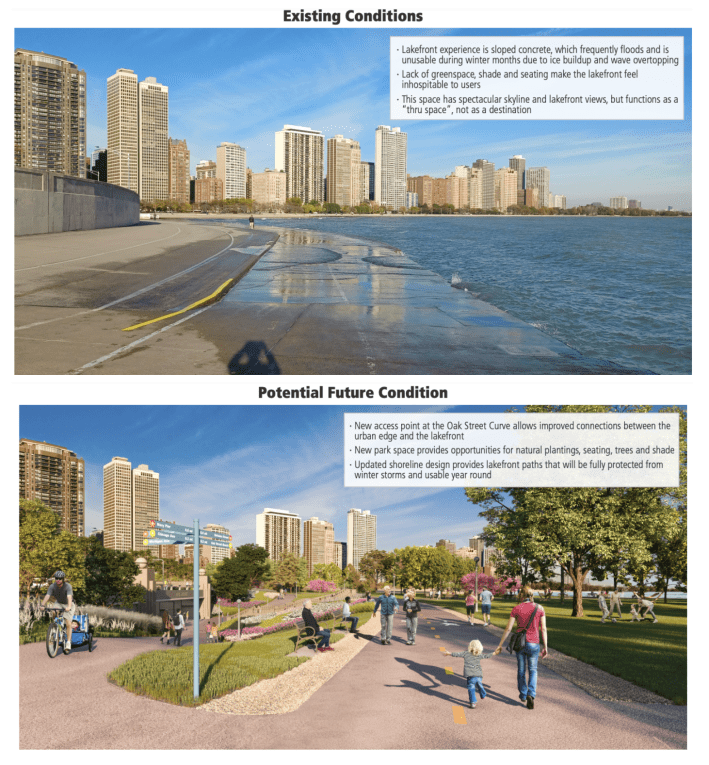

To the south, the treacherous Oak Street curve—the spot where, in 2020, a wave knocked a cyclist off their bike nearly dragging them into Lake Michigan—is unrecognizable in the rendering. The sloping concrete path and fortress-like retaining wall are replaced by separated walking and biking trails amdist gently sloping park land. A new access tunnel connects the surface streets and shady lakefront amenities.

The linear park continues south to Grand Avenue, with dedicated bike and pedestrian paths separated from new, extended revetment walls. The stunner on this stretch is the addition of a large plaza and land bridge from Chicago Avenue to Pearson—extending behind the Museum of Contemporary Art—replete with fountains and covering DLSD, which would be redirected below. Pedestrians could stroll from Michigan Avenue to the water’s edge without losing sight of the sun or stars.

According to the website, roads below lake-level, like DLSD in this rendering, would be protected from high-lake water flooding by the extended, sloping retaining wall and park buffer area, backed by berms. Bike paths would be located at the crest or behind berms as well.

Further north, green space has been added near Belmont Harbor, with elevation changes separating DSLD from bike and pedestrian paths. The Inner Drive at Hawthorne Place is given a similar treatment to the Gold Coast, with Outer DSLD relocated further east, making space for pedestrian islands on the Inner Drive, a bike and walking path, and a modicum of bus boarding space for northbound riders.

According to CDOT and IDOT, the next step in the process is to obtain environmental and design approvals sometime next year. While the renderings were published after several rounds of input sessions and community surveys, the project team is still seeking feedback. Comments can be directed to info@ndlsd.org.