Take the North DuSable Lake Shore Drive Access and Experience at the Lakefront survey here through April 22.

On March 24, the Illinois Department of Transportation hosted the thirteenth task force meeting of the agency’s Redefine the Drive planning project. The purpose of the project is “to improve the North [DuSable] Lake Shore Drive multi-modal transportation facility,” because the infrastructure is beyond its structural life. The meeting, broadcast live on Zoom, outlined next steps and major announcements. This included urban design firm Gehl, famous for its focus on centering people in urban space, joining the planning team. The team also announced a goal of choosing a preferred alternative by the end of the year.

The task force meetings raised many questions about the planning process, public engagement, and public influence on the project’s outcome. Despite being open for public viewing, the task force meeting did not provide the public opportunities to ask questions nor participate in any sort of chat. In fact, since the project was initiated in 2013, there have been only four public meetings and a handful of resident surveys. Overall, the Redefine the Drive team’s planning process could be described as opaque. If that lack of transparency is by design, that's even more concerning.

Molly Fleck, a resident of Lincoln Park who primarily uses transit to get around, expressed frustration about the public engagement process. “Communication with the public is very poor,” she said, noting that the March task force meeting wasn’t publicized. Many public witnesses (members of the public who could view the meetings but are not task force members) learned about it after a slide for the meeting was shared on Twitter by Kate Lowe, a University of Illinois at Chicago urban planning and policy professor.

Given transportation/engineering history, worried about the complexities of lakefill, even for greenspace. Environmentalists, water specialists, perspectives? Also, worried an additional lane ("the addition") & supporting vehicle speed (+VMT, + traffic danger) seriously pursued. pic.twitter.com/8iSX9givi2

— Kate Lowe (she) (@kateontransport) March 22, 2022

“Once I managed to find out about [the task force meetings], the two scheduled meetings were at 9 a.m. and 1 p.m., which interfered with my work schedule,” Fleck said. “I was able to join the 9 a.m. meeting, but the Zoom chat was disabled for members of the public, so we couldn't ask any questions during the meeting. The transparency and openness to public opinion have been severely lacking.”

This is a sentiment shared by Cheryl Zalenski, a Northwest Side resident who previously lived in Roscoe Village. Zalenski also used the word “opaque” to describe the process. She pointed out that most of her information about the project also comes from friends on social media and not project leadership.

“The process has not been very open at all,” Zalesnki said. “It is very hit-or-miss when I find out there are engagement opportunities.” On top of that, Zalenski feels that even when the project team is engaging with the public they’re herding the public towards predetermined outcomes rather than attempting to gather real input and making decisions based on that.

The behind-closed-doors nature of the planning process has not just frustrated members of the public, it has raised concerns that it is preventing better outcomes from being considered and pursued. Zalenski mentioned that when her friends and family learn about this process they’re “pretty shocked and horrified when they hear about how little input is being gathered and how focused on creating more accessibility for [vehicle] traffic there appears to be.”

Fleck likewise expressed frustration at the lack of vision on the part of IDOT, the lead agency for the planning project. She pointed out the irony of quoting famed Chicago urban planner Daniel Burnham on the project website: “Make no little plans; they have no magic to stir men's blood," noting on Twitter, "The vision is essentially just reallocating a couple lanes on a highway. Is this really the best we can do in Chicago? I don't think it is."

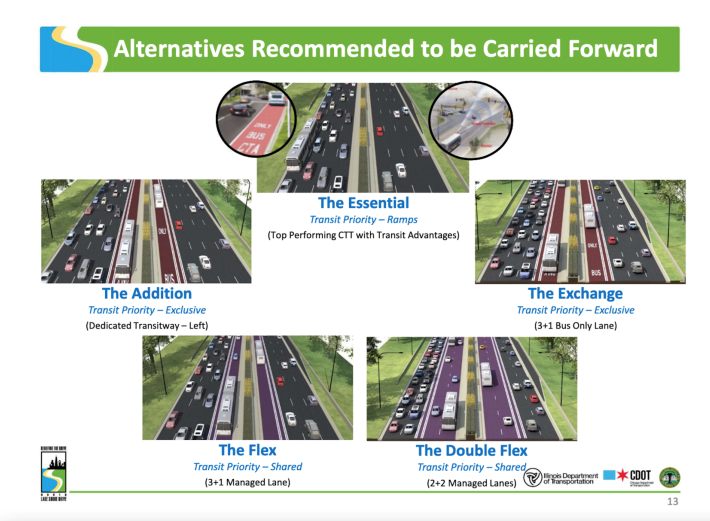

The rapidly worsening climate crisis has added an additional stress point for individuals and organizations concerned about the project and the current redesign proposals for the northern segment of the drive, all of which include maintaining a highway-grade road. Only one of the recommended alternative, "The Exchange," involves converting existing mixed-traffic lanes transit-only lanes.

Michelle Stenzel, a Lincoln Park resident and long-time sustainable transportation advocate, has been a member of the Redefine the Drive task force since it was established. The task force, which is composed of members of the public and representatives of stakeholder organizations, advises and provides feedback to the planning team.

Stenzel wrote a letter to the planning team and several local elected officials, which she shared with Streetsblog Chicago. It opens by asking where is the discussion about climate change. She writes:

The public-facing portion of this project began in 2013, including formulation of its Purpose and Need Statement in 2014, which makes no mention of climate change, an existential crisis we are now facing globally and locally. In recent years climate change has contributed to increasingly severe and widespread weather events causing harm to humans and all life forms. It will likely be at least 15 years before the entire DLSD project is approved, designed and built, by which time climate change will only worsen, without steps being taken to mitigate it.

Stenzel adds: “The importance of reducing greenhouse gas emissions and providing better access to public transit are major themes. In fact, the city has stated an explicit goal of increasing ridership of the CTA by 20 percent by the year 2030.”

Reducing vehicle miles traveled and reducing vehicle dependency (regardless of the fuel source) must be a major component of all attempts at reducing climate change inducing greenhouse gas emissions. The easiest way to accomplish this is by providing more alternative transportation choices to the public and designing infrastructure that makes such choices convenient and safe. IDOT’s plans for the drive would do the exact opposite. They would lock in a dangerous degree of car dependency in one of the few areas of the entire country where people can actually have viable alternatives to driving.

And this is without mentioning the impacts of a highway-grade road on our park and lakefront. Both Fleck and Zalenski view the drive as a barrier to accessing the lakefront. It also disrupts people’s experience of the lakefront, which ideally would offer a green respite from urban living, access to which is widely accepted as being vital for residents’ physical and mental well-being.

Furthermore, the need to cross an eight-lane highway not only disrupts the public’s enjoyment of the lakefront, it also makes accessing it dangerous. For pedestrians and cyclists, the drive is a dangerous barrier. For transit riders, their buses get held up in traffic diminishing transit's viability as a transportation option. This is only exacerbated by the road’s highway grade design standards. This is an issue Stenzel calls out in her letter.

The posted speed limit on north DLSD is 40 or 45 MPH, but few drivers adhere to that limit…a past vehicle speed study done over the course of two days showed that 78 percent to 95 percent of drivers exceeded the speed limit at all times.” She goes on to say that “the geometry of DLSD is not compatible with these driving speeds. Unfortunately, the current design of the DLSD roadway… looks like an interstate highway to the average driver, and so they are “told” by the design that it’s OK to travel at highway speeds of 55, 60, or 65 MPH. As a result of the current design, crashes occur and people die. This is not acceptable.

Indeed.

All this is a serious indictment of the planning process, the planning team’s public engagement, and IDOT’s worldview, especially when applied to dense urban spaces with a high degree of multimodal living. Fleck did not hold back in her criticism of the planning team’s leadership. “Government agencies are not rewarded for good ideas ([although] that’s their job!); but they are heavily penalized when projects fail, so the incentive structure is inherently conservative.”

Fleck does not believe it has to be this way. “I think IDOT could make a case to the public for a bold, visionary plan, but it would require them to stick their necks out and spend political capital. Making NDLSD a true boulevard with transit priority would be a huge risk, and the incentive structure does not support risk-taking. Every piece of the project from public approval to funding would be more challenging, because they’d have to make their case and convince stakeholders at every stage. That’s a lot harder than presenting the kinds of plans they’re presenting now, which essentially preserve the status quo with a few small adjustments.”

Despite the work IDOT would need to put into presenting a bold, visionary plan for the drive and by extension the north lakefront, the times demand it. “Given this opportunity and given the climate crisis we’re experiencing as a world and a city, it’s really disappointing we’re not being more creative about our thinking,” Zalenski said. She closed by saying, “we’re really at a crucial point in the history of humanity when we can make a real bold decision to have a better future. We should seize the moment.” The question remains whether IDOT and other decision-makers are willing to do so.

Take the North DuSable Lake Shore Drive Access and Experience at the Lakefront survey here through April 22.