This piece incorporates previous reporting Streetsblog Chicago freelancer Igor Studenkov did on the November 17 presentation on the Columbus Park road diet for another publication, which never published it.

Was there a flawed public input process for the recent road diet on Jackson Boulevard in Austin's Columbus Park – including pedestrian and bus-boarding islands, plus new bike lanes – particularly in light of the history of racist public policies that have impacted Chicago's West Side? Possibly.

Did Monday's Block Club Chicago article about a backlash against the project, because the street remix made driving a little less convenient, have some issues? Definitely.

Recent Block Club bike coverage

Don't get me wrong, Block Club is generally a valuable news source, and most of its recent bike coverage has been very good. In particular, freelancer Izzy Stroobandt has been doing excellent work, with several deep-dives into bike safety matters.

According to Strava, people definitely ride their bikes here. The map is using data from before the bike lanes were installed. pic.twitter.com/vNWiQHlaEO

— Chicago Fietser (@312fietser) April 11, 2022

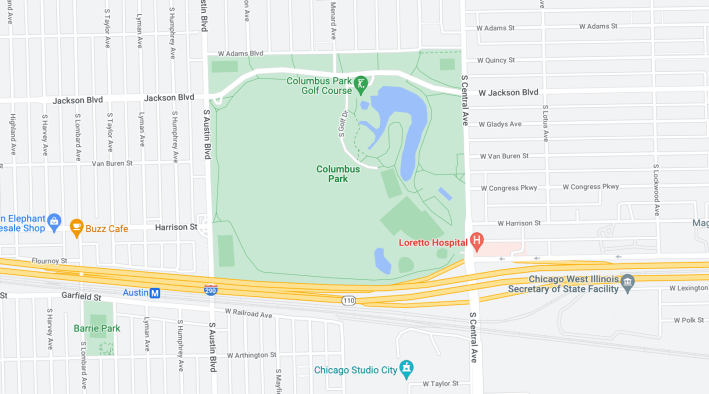

“Why would they do this?" Mildred Salone, who lives north of the park, told Sabino. "It’s absolutely horrible. It’s made it so congested I try not to even [drive] down that way anymore. I go all the way around." She notes that motorists often drive on Jackson through the park to get to and from the Central Avenue access ramps for the Eisenhower Expressway, which unfortunately runs right along the southern border of the green space.

"Salone dreads the situation worsening when traffic picks up as more people flock to the golf course and more youth programs begin at the park as the weather gets warmer," Sabino writes. However, if the new layout encourages drivers to stop using a park road as a high-speed cut-through and take alternative routes to an expressway, is that a bad thing, particularly during times of year when more kids are walking to the park?

Columbus Park Advisory Council chair Bernard Clay told Block Club the council wasn't informed about the plan. However, CDOT spokesperson Susan Hofer told me, "We tried to reach out to the park council, but didn't connect with them before the project started."

“It bugs me that they spent that kind of money, but they didn’t hold any community meetings, they didn’t ask anybody," Clay told Sabino. "We would’ve told them. It’s just ludicrous. It’s a bike path to nowhere.”

Even assuming the earlier CDOT community meetings on new Austin bikeways didn't mention the specifics of the Columbus Park project, there was the November 17 presentation that did go over the details of that initiative. When I noted on Twitter that Sabino didn't fact-check Clay's claim there were no community meetings, Sabino responded that the presentation took place after the project had started construction. CDOT didn't immediately provide confirmation that was actually the case.

But assuming Sabino is correct, his argument that an after-the-fact presentation isn't the same thing as a meeting to collect feedback to shape a project is valid. Still, it's odd that he was aware of the road diet presentation but didn't mention it in his article.

Clay told Block Club that nearby stretches of Lake Street, Washington Boulevard or Madison Street would have been better locations for bike lanes because they're "wider" than Jackson's former four-lane layout. In reality Lake is a two-lane street that already has buffered and flexible-post-delineated bike lanes on it; Washington is a two-lane roadway; and Madison is a four-lane street that has buffered lanes east of Central. Again, Sabino didn't bother to discuss whether or not Clay's assertion was actually accurate.

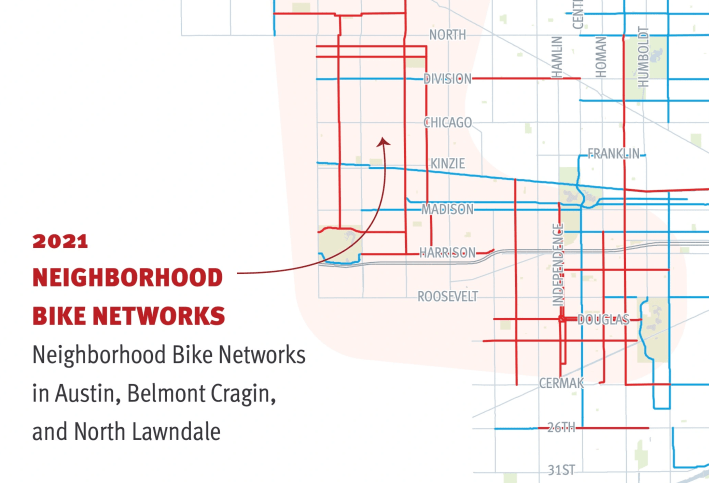

As for Clay's "bike lane to nowhere" comment, that's not completely off-base since the Jackson lanes are about three blocks south of the nearest bikeways on Madison. It is annoying when CDOT installs short stretches of bike lanes with no immediate plan to connect them to other bikeways.

However, that won't be the case after the new bike lanes are striped on Menard and Central avenues later this year. Again, Sabino indicated he was aware of the November 17 ward presentation where those upcoming bikeways were discussed. But his piece didn't mention the fact that the Jackson bike lanes will soon link up with other bikeways.

Moreover, CDOT has been vocal about its intention to create a grid of bike lanes in Austin. As you can see in this detail of the department's map of proposed 2021-22 bikeway locations (which Block Club previously reported on), if the department follows through, the Columbus lanes will be well-connected to the city's bike network.

Sabino writes that the neighborhood residents he interviewed who complained that the Complete Streets project is making driving less convenient told him "not many Austin residents cycle." Next time he does research for an article like this, it would be great if he interviewed Austin neighbors who get around via other modes modes who might appreciate the benefits of the road diet.

Maybe he could hang out at one of the new pedestrian islands and talk to a parent walking their child to the park. Or visit the bus-boarding islands and ask people waiting for the #126 what they think of the new infrastructure. Or, hey, he might even rent a Divvy bike and cruise around the neighborhood to see if he can find any Austin residents on bikes to interview. While none seem to be quoted in the article, in my experience they do exist.

Sadly, quantitative evidence that plenty of people do ride bicycles in Austin comes from data about racially-skewed bike enforcement. A Chicago Tribune analysis found that between January 1 and September 22, 2016, 321 sidewalk biking tickets were written in the community, compared to only 30 in the majority-white, wealthier Lincoln Park neighborhood. In an August 2018 WTTW segment, Chicago Police Department Glen Brooks was surprisingly candid about the fact that the massive racial discrepancy was caused by police officers using zero-tolerance traffic ticketing as a crime-fighting strategy. "When we have communities experiencing levels of violence, we do increase traffic enforcement,” he said. “Part of that includes bicycles."

After an outcry from African-American bike advocates, the number of sidewalk riding tickets issued citywide plunged from over 4,000 in 2016 to only 2,196 in 2018, the Tribune reported. But the ticketing rate was still much higher in Black communities than in majority-white ones. Building a network of safe bikeways in neighborhood of color will make it easier for residents to avoid sidewalk riding tickets.

Next time Sabino interviews people who are upset about a traffic safety initiative because motorists can no longer drive as fast as they've been accustomed to, he also might try to talk to local residents who've been impacted by dangerous driving in the neighborhood. Here are a few cases in Austin he could look into.

The community input question

Despite all these issues, the Block Club piece isn't totally invalid. Sabino didn't actually prove that CDOT dropped the ball in terms of informing residents about the project and providing opportunities for input. But his article makes it clear some neighbors feel they didn't get a fair chance to provide feedback.

It's in CDOT's interest to take a cover-all-bases, belt-and-suspenders approach to community outreach for such projects, so that residents can't reasonably argue they never had a chance to weigh in. That's particularly true in neighborhoods of color that have often gotten a raw deal from City Hall in the past.

The best thing in Sabino's article is words of wisdom on the controversy from Oboi Reed, a North Lawndale resident who leads the mobility justice group Equiticity. "When the bike lanes drop out of nowhere… people are just turned off. People have to feel ownership and excitement over it."

"When people don’t even know about it, it creates this adversarial reception of the bike lanes,” Reed added. “There could be people who, had it been done the right way, they could have been enjoying these bike lanes.”

The Active Transportation Transportation is pretty much on the same page with Reed on the issue. "This is a needed project to prevent traffic crashes and make Jackson safer for everyone, particularly people walking and biking who are most vulnerable," spokesperson Kyle Whitehead told me. "Design changes like this are necessary to slow down car and truck traffic to safe speeds, especially on streets like Jackson that run through a popular public park. Alderman Taliaferro and CDOT deserve credit for leading with safety here."

But Whitehead added, "Stories like this one demonstrate why the city’s planning process for safe streets projects needs to be improved to make information and opportunities for input more accessible for all residents. There will always be tradeoffs and some residents may not be happy with the results, but no one should feel shut out of the process."