On a recent visit to New York, I took a stroll down the middle of Vanderbilt Avenue in Brooklyn, one of 20 sites in the city’s Open Streets program, created in response to the pandemic, that has been made permanent. The good vibes on Vanderbilt that sweltering Saturday afternoon were palpable the moment I glimpsed the barricades that made space for hundreds of people of various ages walking, biking, skating, and playing. It’s a space that provides an immediate jolt of joy, and welcome relief from the noise, exhaust, and general stress of motor vehicle traffic.

Chicago’s Slow Streets program (the city calls them "Shared Streets"), by comparison, was adopted late in the pandemic and is not nearly as extensive as many of its peer cities, but this shouldn’t stop the city from expanding and making the program permanent. As a recent “Downtown Futures Series” talk hosted by the Chicago Loop Alliance discussed, urban design that makes space for residents to safely and easily interact with the outdoors and each other plays a major role in both physical and psychological well-being.

The hourlong event was entitled “Designing Cities for Mental Health” and featured two guest speakers: Jennifer Roe, author of the upcoming book “Restorative Cities: Urban Design for Mental Health,” and Margaret Frisbie, executive director of Friends of the Chicago River. Moderator Dave Broz, principal at the architecture and design firm Gensler, opened by observing, “The pandemic brought home just how much urban design can affect mental health. City dwellers with poor pedestrian or cycling infrastructure or limited access to parks or plazas or no nearby areas for public interaction suffered in isolation.”

Broz said that, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, anxiety was three times more prevalent in 2020 than 2019 and depression was four times more prevalent. As we come out of the pandemic, increased awareness of mental health issues provides an opportunity to rethink public space, prioritizing the well-being of citizens over the interests of industry and the speed and storage of cars.

Broz then introduced Roe, who outlined the seven pillars for restorative cities she identifies in her book: green cities that have equitable, well-maintained green space; blue cities that have equitable access to water; sensory cities that are designed with pleasant sound, smells and visual elements like lighting design and public art; neighborly cities that facilitate social relationships; active cities that promote multi-modal transit and integrate physical activity in everyday life; playable cities that provide space for structured and unstructured play; and inclusive cities designed for people of all ages, genders, sexual orientation, socio-economic strata, and cognitive abilities and needs.

Clearly, these concepts overlap: Programs like open streets can be designed with plantings, public art and playscapes, and even blue elements like fountains, while providing space for neighborly encounters, and active mobility and play. As Courtney Cobbs recently wrote for Streetsblog, pedestrianizing roadways around schools not only makes these streets safer for kids coming and going to school, but also adds much-needed space for them to run free.

Like Cobbs, Roe pointed to the Barcelona superblocks as an example of urban design that integrates physical activity and mobility in everyday life. “These are mixed-use communities, multi-modal streets, with street connectivity, subsidized and integrated public transit and street trees and urban greening,” Roe explained. “The mental health benefits of such design include reduced risk of depression, anxiety, improved stress regulation, improved brain health and memory functioning—all important for healthy aging and child development.”

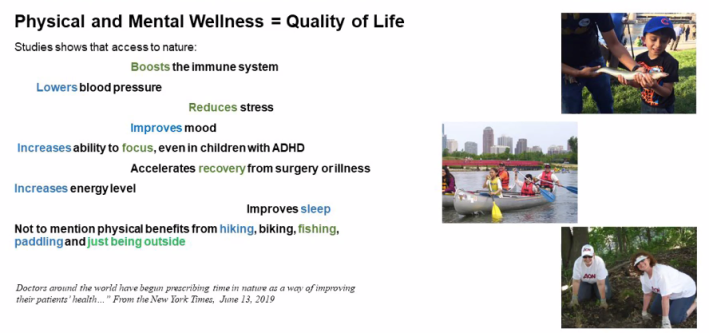

Frisbie presented on the importance access to water, parks, wildlife, restored landscapes and trails to mental well-being. She also noted how paths along the river can raise public awareness of environmental issues. Frisbie said the media began contacting Friends of the Chicago River about sewage in the river and flooding once the Riverwalk was built. “The Riverwalk was designed to flood, the city knew that would happen, but nobody cared because they didn’t understand there was sewage in the water, but when the Riverwalk was underwater, suddenly they cared,” she said. “The message of the river having this serious problem—85 percent of those occasions are gone—but it still happens, and people need to be told about it and to say it’s unacceptable.”

During the Q and A, an attendee asked about the availability of data that correlates, for instance, miles of bike lanes to mental health statistics to help advocates make the case for infrastructure investments. Roe said that more data is needed on the connection between physical activity and mental health. However, Frisbie cited a study that found that for every dollar spent on development of blue/green corridors, $1.77 was created in local wealth. She also noted the danger of gentrification with river edge development. “At the same time we’re giving the river back to people because it was fenced off, we have to be careful we’re not taking it away,” she said. “Blue/green corridor development increases land value, but not so much that property values skyrocket.”

Broz closed the hour by saying that a return to the old normal, with commuters coming back to fill cubicles is a “miscalculation of human behavior.”

“There are aspects of a new normal that are better than before,” he said. “We’ve discovered the river system, we’ve discovered our neighborhoods, we’ve discovered our neighbors and we’ve realized we don’t need to take a plane ride for a 45-minute meeting across the country. We don’t need to sit in a car for a commute into the office to have focus time. Downtown business districts are changing to social districts. And with the river, Millennium Park and world-class museums, Chicago is well-poised to make this transition and maybe better than many cities across the globe.”

Broz cited the Loop Alliance’s upcoming Sundays on State open street program beginning July 11, which will pedestrianize State Street from Lake to Madison on Sundays throughout the summer for a block party, as a step in this direction.