The shortcomings of Chicago area public transit are self-evident to any suburban transit rider who has ever tried to get anywhere but the Loop.

Metra lines all terminate at the Loop and their pre-pandemic schedules tended to favor suburb-to-Chicago commuters. Pace bus network was created from multiple suburban bus systems, which can still be seen in how service levels and route coverage can vary wildly depending on where you are. And while CTA has a network of “night owl” services throughout the city, Pace only operates a handful of less frequent night routes across a much wider area, and Metra doesn’t have any night services at all.

On March 24, Active Transportation Alliance organized the Future of Suburban Transit Forum to delve into the challenges essential workers face when trying to get to jobs outside the city, a space that doesn't get much transit service. ATA and Metra and Pace heads agreed that the COVID-19 pandemic offers a unique opportunity to experiment with services. The trick is getting the funds to pay for it, and overcoming structural challenges, especially on Metra’s end.

The State of Suburban Transit

Like most American commuter rail networks, Metra remains commuter centric. Anyone who wants to take a train from one suburb to another has to go through the Loop, and the one attempt to create a suburb-to-suburb commuter line has been shelved. Most pre-pandemic schedules prioritizes commuters heading to work from Chicago, though there were a few exceptions. BNSF Line had a similar number of rush hour express trains going in both directions between Chicago, Naperville and Aurora, Metra Electric’s service from downtown to Hyde park was beefed up, and so-has the reverse-commuting service on Milwaukee District North line. But, at the other extreme, Heritage Corridor is rush-hour only, North Central Service barely had any reverse-commuting options, and both had no weekend service whatsoever.

Pace has a number of suburb-to-suburb routes, but service tends to get sparser the further one gets from Chicago. Major cities like Joliet, Naperville, Aurora, Elgin and Waukegan have decent service, but surrounding municipalities have large service gaps. The headways are often longer than CTA’s, and service level drops sharply on weekends. For example, before the pandemic, 21 routes operated in Lake County on weekdays, but only 12 of them operated on Saturdays and only two operated on Sundays – which hurts essential workers who work weekends.

While CTA has two ‘L’ lines and “night owl” buses serving major corridors, Metra has no night service whatsoever and Pace only has six bus routes running at night. All but Route 352 are geared toward UPS shift changes, which leaves large service gaps.

The Forum

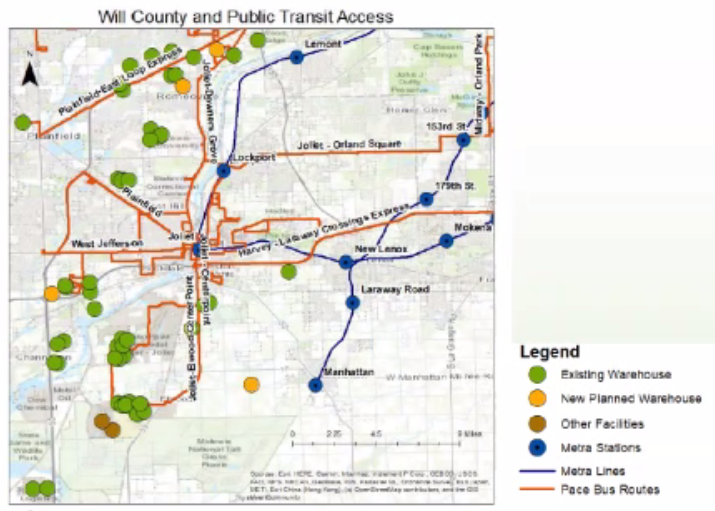

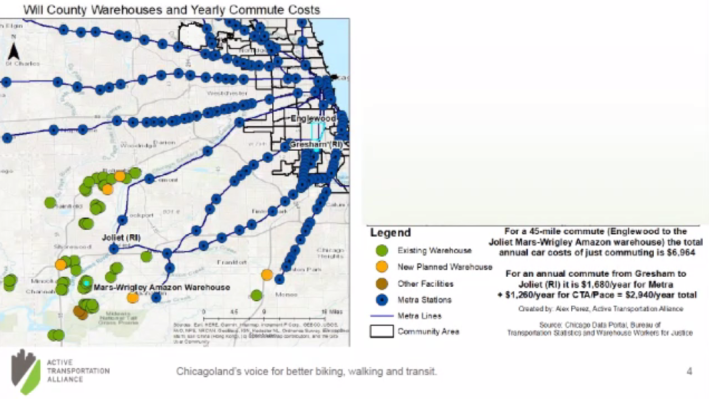

Throughout the pandemic, transit officials, especially Metra officials, said that they would be open to major schedule changes in response to changing demands during and after the pandemic. W. Robert Schultz III, an ATA campaign manager, said the transit agencies must “Build Back better” and ensure that the system responds to the needs of essential workers and transit riders in Black, Hispanic and immigrant communities. As he noted, Amazon and other companies have been building warehouses and processing facilities around Joliet and in south suburbs, but transit services haven’t kept up with demand.

As ATA's analysis spotlighted, three Pace routes that serve major Joliet area warehouses and distribution hubs – Route 361, Route 511 and Route 512 – only run 1-2 times a day, and none of them run on weekends. The schedule becomes even more limiting for workers outside Joliet area – for example, making the Route 512 only trip to CenterPoint Intermodal Center would be impossible to a Chicago resident, because the earliest outbound Rock Island District train doesn’t get to Joliet until 7:20 a.m., 50 minutes after the bus leaves.

Alfred White, worker leader at Warehouse Workers for Justice, said that, since his car broke down, he experienced those shortcomings first-hand.

“I have to be up at 12:00 a.m. to start a job at 6:00 a.m., [compared to two and a half hours by car]” he said. “And because I have to have to travel, there's so much commute time, I'm not able to get enough rest.”

White didn’t elaborate on what routes he took, saying only that he has to walk about an hour from his apartment near the lake to get to 95th-Dan Ryan Red Line ‘L’ station and wait another hour for the Pace bus. The fact that service is so sparse and the commute is time-consuming, it means he can’t get as many hours as before, which puts him at risk for losing his apartment.

“I work 8-9 hours, and I gotta commute six hours round trip,” White said. “It just makes no sense.”

Alex Perez, ATA’s advocacy manager, said that the major issue for workers is that, while transit is cheaper than driving, “the waiting makes the trip a lot longer, even though it's chapter than driving by car, and I think that's a big factor why people don't take public transportation.”

It’s also why, Perez said, there are private van services workers take advantage of – they cost $50 a week, “but it does give them reliability to get to and from work.”

It should be noted that Pace operates a Vanpool program, where the transit agency supplies the vehicle and covers vehicle-related expenses, and the driver and the passengers pay a monthly fare. The cost vary depending on the distance traveled and the number of passengers, but the more passengers ride, the lower the costs are – and even the most expensive fare ($174, for up to four passengers who travel 151-160 miles) is cheaper than $50 a week.

Metra Executive Director Jim Derwinski said that, for Metra, the biggest obstacle to adding service is having to share the tracks with freight trains. MED has “the biggest flexibility” as the only line where freight and passenger trains use separate tracks. He said that BNSF Railway, which owns the tracks and operates the line under contract with Metra, does a good job of keeping freight and passenger trains moving, but Canadian National railroad, which owns the tracks used by the North Central Corridor and Heritage Corridor, hasn’t been as accommodating.

Pace Executive Director Rocky Donahue said that Pace buses have to deal with the same traffic conditions as cars, and truck traffic is a major problem around warehouses. His agency has been trying to address it by investing in streetlights that would give the buses signal priority, as well as establishing Pulse Arterial Rapid Transit corridors and making various service improvements to speed up routes that use expressways.

The second round of stimulus mostly benefitted the CTA, but Derwinski (Metra) and Donahue (Pace) expressed hope that their agencies will get more funds from the most recent stimulus. They also argued that the RTA’s regular funding formula is out of step with Chicagoland’s needs.

“At this point in time, it's understandable how RTA approached it, but at the end of the day it didn't include suburban needs,” Derwinski said. “As [transit] needs changed, we're forced, as operators of those service boards, into positions that aren't beneficial to broader needs of region.”

Both praised the Fair Transit South Cook pilot, because they wouldn’t have been able to experiment without county funding.

“I would say replicating this model would require that we prioritize accessibility and investing in transit,” Donahue said.

“It's all about volume,” Derwinski said. “At the end of the day, those things cost money. [If] more people use it at lower cost, you make up for that differential.”