Last week the Transportation Equity Caucus hosted a webinar on the “History of Enforcement in Transportation.” The featured speakers were Anita Cozart of the Washington D.C. Office of Planning; Río Oxas of RAHOK, a consulting service focusing on "race, ancestors, health, outdoors and knowledge"; and Chicago’s own Oboi Reed form the mobility justice nonprofit Equiticity. Axel Santana of the racial and economic equity think tank PolicyLink moderated the discussion.

In this age of a new consciousness around racial injustices in all sectors, it’s important to know the history of racism in transportation planning in an effort to prevent replicating past harms. This discussion was organized to discuss how overpolicing and enforcement crackdowns cause harm in communities of color. The Transportation Equity Caucus is working to challenge the narrative that more policing makes individuals and communities safer.

The discussion began with a brief historical overview of the history of law enforcement. Santana opened up the panel stating that some of the early southern American police forces were born out of slave patrols. In other parts of the country, groups of men were hired to protect the property of the wealthy. After the Civil War during Reconstruction, many local sheriffs maintained a similar function to the slave patrols through their enforcement of segregation and disenfranchisement of previously enslaved Africans. “Enforcement started out and continues to predominantly be about protecting wealthy and white comfort at the expense of the lives of Black and Brown folks,” Santana argued.

The invention of the automobile represented a new threat to public safety, with the first U.S. automobile fatality taking place as early as 1899. Regulations were needed to prevent reckless driving, and police began enforcing speed limits and other safety laws. However, traffic tickets also became a potential source of income, and "revenue policing," officers making traffic stops with the goal of raising money for local municipalities, was already fairly common even before mass production of cars began.

Santana shared a quote from Cotton Seiler, author of Republic of Drivers: A Cultural History of Automobility in America: “Policing the roads was always about more than just public safety. It was about the exercise of various types of power: local power, racial power, and making money.”

In the modern era, researchers at Stanford University analyzed data from close to 100 million traffic stops between 2011 and 2017 and found Black drivers were more likely to be pulled over and have their car searched than white drivers, which the researchers stated was evidence of systemic racial profiling. Latinos, Asian Americans, and Pacific Islander Americans are also disproportionately stopped while driving, which in many cases can lead to arrest and deportation. According to the U.S. Bureau of Justice, the traffic stop is the most common interaction between U.S. residents and police officers. It is understandable that members of these these communities may feel distrust and uncertainty when interacting with law enforcement.

The over-reliance on police for traffic enforcement in the U.S. has a serious impact on freedom of mobility for Black and Brown people. With this understanding, the first question to the panelists was around their “origin story” or what experience led them to their work as an advocate for racial equity in transportation. Reed shared his experience of hanging out with friends “being rambunctious teenagers” and two or three police cars surrounding him and his friends. Officers quickly jumped out of their cars with their guns aimed at the teens. A Black officer stated, “All right guys, same ol' [N word] s---” to his fellow officers to signal that their response was unwarranted. Read a full account of the story here.

Looking back on that experience Reed wonders what would have happened had one of his friends reached in his book bag for their wallet or if someone had smarted off to one of the officers. Reed fast-forwarded in time to the murder of Laquan McDonald. It was at that moment Oboi realized he needed to be more intersectional in his work. “I couldn’t work to increase active transportation in our neighborhoods and not be deeply concerned about what it means for more Black, Brown, and Indigenous people to walk and bike in our neighborhoods and potentially put them at greater risk of biased, racist policing in our city. I knew I needed to focus beyond transportation and focus on racial justice and racial equity. All of that gave birth to Equiticity.”

Río Oxas, who uses they/them pronouns, shared their experience growing up with undocumented parents and how that impacted their family’s mobility. “Growing up I thought about what things to say, where, and who should pick me up and who shouldn’t.” In high school they needed to ride the bus to get to a summer school program and their family could not afford bus fare. They were once kicked off a bus due to nonpayment.

Another time Oxas was riding a bike and failed to signal a right turn which resulted in three police cars surrounding them. They were able to reason with the officers. Sadly they have been stopped multiple times while riding a bike. “Because I am perceived as very masculine, I could be shot because of the fear of the Brown masculine people. Black and Brown masculine bodies are very feared.”

Oxas also shared that they have a partner who is also masculine and their partner has a police record. They sometimes have to negotiate who will drive. “Those microstressors are equivalent to a major trauma.”

Oxas' organization RAHOK, an acronym for Race, Ancestors, Health, Outdoors, Knowledge, was founded because “it is in that outdoor space that the racial tensions that we find ourselves in is also the source of our health.” They believe that many people of color spend more time indoors due to fears of interactions with law enforcement.

Cozart grew up in the eastern suburbs of Cleveland. Her mother wanted to raise her children in a more racially-integrated environment compared to the segregated southern U.S. that she grew up in. However, Cozart said that the city of Cleveland was “hypersegregated” during the time she was growing up. Jobs were more likely to be located in the white part of town which required lengthy commutes for Black residents. Growing up, transit was crucial for traveling through her city.

She saw that many of her Black friends experienced disinvested schools and disinvested transportation amenities compared to white neighborhoods and suburbs. As an adult, she learned “there are sets of policies and people that were instrumental in weaving racism into the very fabric of our streets, our sidewalks, where there are no sidewalks, where there are no good, quality bridges.”

Santana then asked panelists how they feel marginalized groups have been targeted by police in the past. Reed was the first to respond. “The vast majority [of the contact] that BIPOC [Black, Indigenous, and People of Color] folks have with the police is in the act of exercising our human right to mobility….The vehicles of mobility are our sidewalks, trains, buses, and vehicles that are a major part of our cities. That’s where the collision happens.”

Reed noted that's a harmful situation because people require mobility for improved educational opportunities, job opportunities, opportunities to improve their health, etc. “When our mobility is restricted, any number of life outcomes become constricted. The nature of policing in [Chicago] is to constrict our movement." He referenced slave patrols as "the foundation of policing.”

Reed said he is more concerned with the policies that underpin policing than the actions of individual officers. Cozart argued that these protocols come from the value of erasing the history of BIPOC.

Oxas referenced the Trail of Tears, and said the U.S. government pitted Black and Indigenous people against one another. They also discussed the Native American boarding school system during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, in which children were forced to abandon their Indigenous identities and cultures, and the modern-day school to prison pipeline as examples of extensions of the policing system.

Panelists were then asked why it’s important to look at the history of policing in transportation and what implications it has for BIPOC, disabled, and LGBTQ communities today. Cozart said her understanding of urban planning and design in Washington D.C. was influenced by the treatment of the culture surrounding Go-go music, a genre of funk that's indigenous to the the region's Black community. She referred to the book the book Go-Go Live: The Musical Life and Death of a Chocolate City by Natalie Hopkinson, which argues that the art form was strategically criminalized in conjunction with the displacement of many Black D.C. residents from the city to the suburbs by gentrification and rising housing costs.

Oxas discussed the violence trans women face on the street, the overrepresentation of trans and disabled folks in the criminal justice system, arguing that people who are not working to abolish the police are complicit in these injustices.

Reed stated that history is currently repeating itself in structures that make up our society. He argued that the fact that Chicago’s Vision Zero program to eliminate traffic deaths, announced in 2016, not long after the Laquan McDonald police murder scandal broke and the U.S. Department of Justice’s issued scathing review of local policing practices, still heavily involved the police department was an example of institutions ignoring recent history. The following year, the Chicago Tribune reported that the police department was writing exponentially more bike tickets in Black neighborhoods than majority-white ones.

“The reason we focus on history is that when it’s ignored we keep living it over and over again," Reed said. "I’m interested in history because I want to show the world that the systems we put so much faith in are rooted in structural racism. The most important work we must do is the dismantling of that structural racism.”

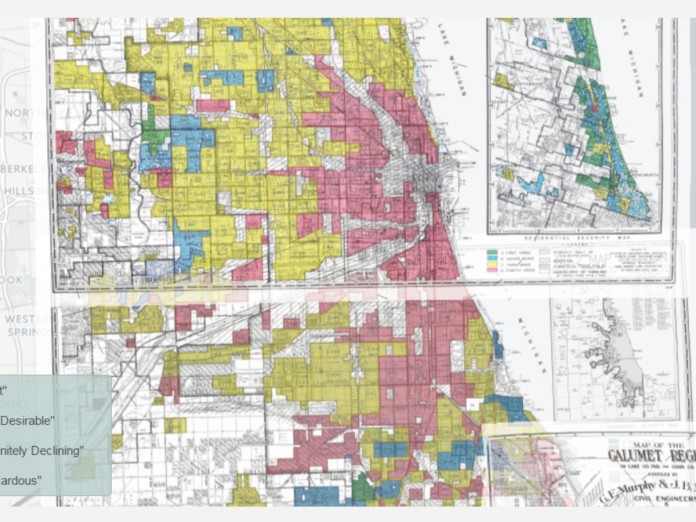

Santana asked how housing, public health, jobs, climate, and other aspects of life intersect with the history of policing and transportation. Cozart pointed to redlining. “It’s a pretty clear example of structural racism that impacted the public sector, private sector, non-profit sector. It was based in and supported by ensuring there was a police force that could segregate Black people and people of color in certain neighborhoods bounded by lines on a map.”

Cozart argued that these sets of strategies were based on the decision to starve communities of color of resources. She added that inequities reenforced by transportation infrastructure are a persistent issue, noting that residents who live next to bus depots that are polluted with diesel fumes, or in communities walled off by expressways, or in other areas impacted by environmental health risks, are usually people of color.

“I always think about mobility justice literally being the intersection and the arteries of every social justice movement," Oxas said. "It’s how we get to school, work, the clinic, our friends, the mountains, the ocean. That’s mobility justice.” They added that everyday, seemingly benign things can be connected to policing.

For example, Oxas lives in the Echo Park neighborhood of Los Angeles. In the early 2010s, a gang injunction, a civil court order that uses a lower legal standard than required by the criminal justice system, was placed on the Echo Park neighborhood in Los Angeles. The injunction was announced on the same day Echo Park Lake was reopened after a renovation. The epicenter of the gang injunction was the lake and any point three miles from the lake was under the injunction.

Oxas said the police activity during a gang injunction is so intense that a child could be questioned by police on suspicions of gang activity for such mundane things as wearing certain colors. One of the suspect colors was the bright blue color of the LA Dodgers baseball team jerseys, despite the fact that Dodgers stadium was within the boundaries of the gang injunction.

Reed highlighted the need to be to consider issues of race and class when doing transportation and traffic safety advocacy. “When we avoid being intersectional, it’s deadly in our neighborhoods. [People of color] don’t have the luxury of being narrow-minded or only focused on one particular sector or policy issue. We need policy makers to be intersectional.”

Reed said that when he first started organizing community bike rides in predominantly Black and Brown lower-income neighborhoods, he heard from young people that they didn’t ride their bikes because they felt they were being targeted by the police. That was a new concept to him at the time, but he took their word for it. He added that when he shared the youths' concerns with mainstream transportation advocates and Chicago Department of Transportation officials, often the response was disbelief -- people didn't believe the police were actually guilty of profiling cyclists of color. But years later the Tribune data proved that officers were, in fact, writing exponentially more bike tickets in communities of color, and a police spokesperson eventually admitted that this was due to bike enforcement being used a pretext to conduct searches in high-crime areas.

This and other experiences lead Oboi to conduct research to better understand how barriers to transportation access transportation serves impact life outcomes in communities of color on the South and West side. He found that some residents were making transportation choices to avoid the police. “There [aren't] two separate conversations: transportation or enforcement. It’s one conversation given the nature of our society where structural racism is the rule of the day….We have to consider transportation and enforcement as linked together and we have to consider them both.”

Reed discussed the 79th/Stony Island/South Chicago intersection, where the Avalon Park, South Shore, and South Chicago neighborhoods meet. The intersection is the most dangerous junction in the state in terms of crashes, but no major changes have been made to increase safety. Reed toured the area with U.S. Department of Transportation officials five years ago and said there has been no sense of urgency in decreasing injuries and deaths around this intersection.

“Before there were stay at home orders, there were people who were under their own stay at home orders; not because it was healthy but because they wanted to avoid police," Cozart argued. "Or because the infrastructure that we have created around people is to tell them they don’t belong.”

Finally Santana asked the panelists what policies they felt have done harm in marginalized communities and need to be done away with or redesigned, and how BIPOC have led the charge for a new vision of safety within their communities.

Reed started off by arguing that the implementation of Vision Zero, which launched in Sweden in 1997 and has been credited with a 34.5 percent reduction in traffic deaths in that country, has been "racist" in the U.S., a far more ethnically diverse nation, with much higher levels of income inequality. He asserted that Vision Zero has been "harmful to Black, Brown, and Indigenous people" in this country.

Reed argued that Black and Brown transportation advocates were initially ignored when they criticized Vision Zero’s reliance on enforcement, and that advocates of color have only recently been taken seriously due to heightened media attention to racial injustices. Instead, he asserted, the focus should be on education and street redesigns to promote traffic safety.

Oxas discussed work they did for People for Mobility Justice titled Vision Incomplete. Santana highlighted the Transportation Equity Caucus’ advocacy work for more equitable and accessible grantmaking in transportation funding.

During the Q & A the panelists were asked how they would respond to folks who feel that police are needed to address traffic violence. Oxas argued that groups such as the Black Panther Party, the Brown Berets, and Los Angeles' Red Guards represent community-based and culturally relevant forms of accountability that are an effective alternative to police. “Policing is inhumane and actually strategically dehumanizes and objectifies people as part of a system that is meant to make money and devastate communities and cultures,” they said.

Santana noted that the Oakland Department of Transportation has been working with artists and other creative individuals to find culturally relevant approaches to traffic safety.

One audience member asked Cozart about her experience as an urban planner and whether she experiences microagressions in policy efforts regarding transportation and race. She responded that many sectors are are experiencing a racial reckoning at this time, and planning is no exception. She added that she is outspoken in her support for BIPOC in planning and noted that a microagression can be anytime you tell the truth and it falls on deaf, hostile, or vengeful ears. She noted that microagressions happen in all aspects of planning, in both public and private settings. “It’s something we have to acknowledge, acknowledging what has happened and is happening.”

This discussion was the first of a three-part series. You can stay updated via the Transportation Equity Caucus’ Twitter account.