The Chicago Department of Transportation is asking residents to share their observations of pandemic-related transportation and public space issues — like dangerously crowded sidewalks and speeding drivers endangering cyclists — and to provide suggestions for addressing these problems. You can provide input at covidmobility@cityofchicago.org. Be sure to mention details about the issue such as the nearest intersection. You can also complete a survey to weigh in on Mayor Lightfoot's reopening plan for the city.

At this point just about all blue-state big cities (and a few red-state ones as well) are opening streets to make room for safe, socially-distanced walking and biking during the COVID-19 pandemic. Chicago is a notable exception: Mayor Lori Lightfoot has closed 22.5 miles of trails, including the Lakefront Trail, the Chicago Riverwalk, and The 606, but she has so far shown relatively little interest in doing an open streets program.

However, the tide may be starting to turn as more people join the chorus calling for opening streets in our city for walk/bike. Streetsblog Chicago was doing so even before Lightfoot closed the trails. Other transportation advocates have been lobbying city officials and gathering signatures on petitions.

Last Wednesday the Active Transportation Alliance, which initially indicated that it wasn't going to push for more space for walking and biking during the pandemic, announced that it has been talking with the mayor and other officials about the possibility of doing open street and other interventions to help prevent a post-COVID spike in driving. And on Friday WBEZ reported that African-American teens say "there aren’t enough green spaces on the South and West sides to practice proper social distance now that it’s warming up," a problem that could potentially be addressed by opening streets.

One of the latest voices advocating for open streets is the Loop-based firm Hammersley Architecture, which recently drafted and posted on their website a Chicago Promenade Plan. Principal architect Brian Hammersley said that the proposal is meant to be a catalyst for conversation and feedback from a design perspective. “We’re trying to come up with something broad and widely-applicable,” Hammersley said. “So it’s not about a certain space in the city but all spaces in the city. And something that could be done in a quick manner. We’re seeing weather change, attitudes change and a lack of continuity of opinion. We wanted to be able to get ahead of that and propose something that could be widely useable.”

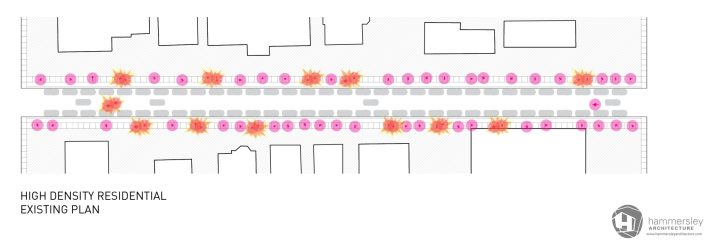

The Hammersley plan makes the case for open streets with census data and a measuring tape, calculating the “occupancy” of a typical residential street under the 6-foot physical distancing guidelines -- drawn in the plan as a circle of 28 square feet per person. Two scenarios are considered: a typical high-density residential block, with a mix of high-rise and mid-rise residential buildings and about 1,050 residents per block; and a typical regular city residential block, with a mix of multi-family, single-family, and 2-6 flats and about 400 residents per block.

According to the Hammersley’s calculations, under the current circumstances in which pedestrians are restricted to narrow sidewalks, 71 percent of residents on a typical city block, and only 23 percent of residents on a high-density block, can be outside on the block they live on at the same time. But Hammersley calculates that if we open streets, even accounting for the space occupied by parked cars, the outdoor occupancy of a street would more than double, allowing 56 percent of residents of high-density blocks and more than 100 percent of folks on typical residential blocks to be outside on their street at the same time while maintaining social distance. The plan recommends addressing this disparity by creating open streets route that connect high- and low-density areas to allow people to disperse across several blocks.

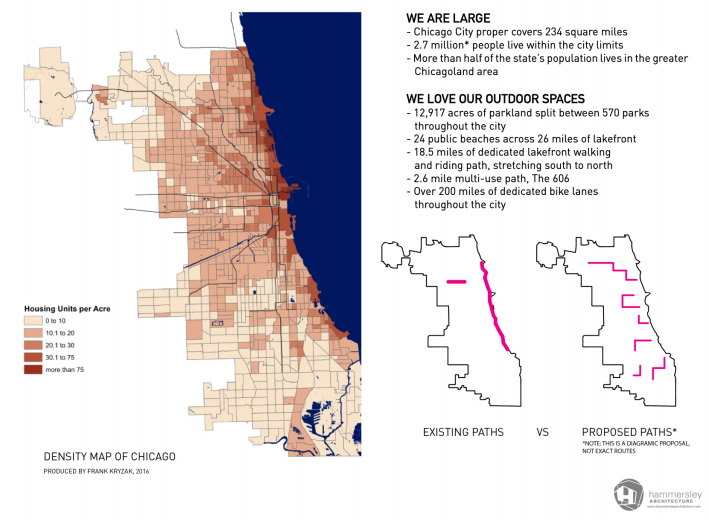

No specific routes are proposed, but a simple map graphic indicating how paths might be situated suggests an approach akin to Oakland’s extensive Slow Streets plan or Charlotte, North Carolina's recently-announced Shared Streets, both of which close residential streets to through-traffic while allowing low-speed vehicular access for visitors, delivery personnel, and first responders.

The plan suggests design criteria that align with similar open streets programs in other cities, like restricting traffic on residential streets only, not interfering with bus routes, and closing stretches of significant lengths to encourage people to move through the space for essential trips and transportation, rather than to congregate in one place. The plan also calls for community members to provide input on which streets to close and how.

Hammersley says his next step is to invite community feedback. “We’re putting together a survey to collect information about people’s perspectives on this,” he said. “We’ve been approached by certain neighborhood groups to talk about this, but the far-reaching goal is to play out these ideas through community input and data.” Hammersley intends to work with community organizations and aldermen's offices to gather data.

The plan does not include specific recommendations for implementation, but Hammersley said in our interview that whatever the plan finally looks like, it should not be policed. “Part of the conversation for us is how it looks different in different places, which is why we put out a guideline set and not what to do here or there,” he said. “It could be very different in different places. This could be a vehicle for equity.”

Active Trans initially cited concerns that an open streets program would be too expensive and resource-intensive, distracting from efforts to help hard-hit communities of color during the pandemic, and that it would almost certainly require lots of extra policing. However, Oakland has demonstrated that open streets can be implemented with low-cost measures like traffic cones and signs and maintained without law enforcement.

Ultimately, Hammersley hopes to aggregate data and produce some usable tools for the city and other key partners. “The goal is to collect all this feedback from multiple stakeholders, get it in one spot, and funnel it into something the city does,” he said. “We’d like to collaborate with people who specialize in this work.”