In late 2017, after years of complaints from Uptown residents to 46th Ward alderman James Cappleman about tent cities in the Lawrence and Wilson avenue viaducts under Lake Shore Drive, the Chicago Department of Transportation installed bike lanes on the sidewalks. While so I've found no smoking gun proving that the city's motivation for building the cycling infrastructure was to prevent homeless people from returning to the underpasses afterwards, it's highly probable that was at least a factor in the decision.

Ironically, that defensive architecture strategy isn't even working. As of this afternoon there were two tents on the south sidewalk of Lawrence, and three or four tents plus a couch and a shopping cart on the north sidewalk of Wilson. While the green bike lanes are largely clear, the encampments basically render the pedestrian portion of the sidewalk unusable. That isn't a big deal this time of year since bike and pedestrian traffic is light, but could lead to conflicts during the warmer months.

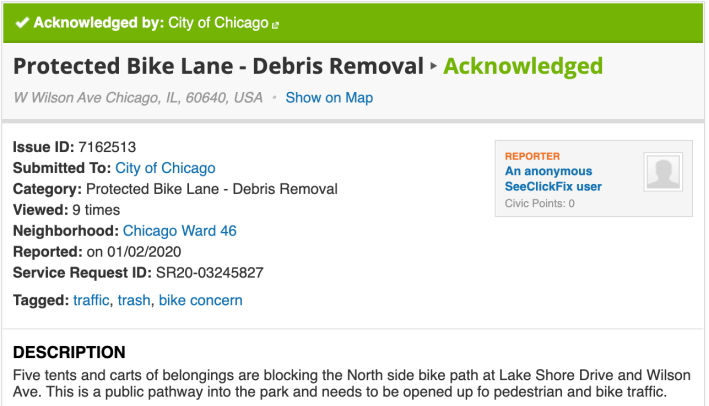

Streetsblog Reader Melanie Eckner alerted me that someone notified the city about the new encampments via the 311 service request system yesterday. "An abuse of the new 311 codes, if you ask me," Eckner said.

The 46th Ward and CDOT didn't immediately respond to requests for updates on the situation.

Former residents of the tent city, represented by the Chicago Coalition for the Homeless Law Project, previously sued the city over the issue, arguing that the installation of the bike lanes was discriminatory against the homeless because it was done with the sole purpose of displacing them. The lawsuit also asserted that the design of the bikeways is dangerous.

Several months ago a judge granted the city's motion to dismiss the lawsuit, according to the coalition’s policy director Julie Dworkin. "The judge argued that that the design didn't discriminate against homeless people because no one is allowed to camp there, but we said the impacts were disparate," she told me today. "It was basically a bad judge."

Dworkin said that homeless people started returning to the viaducts four-to-six weeks ago when a single tent was pitched, and more soon followed. Not long after that, the city started posting weekly viaduct cleaning notices, requiring the tents to be removed for most of the day every Monday.

On Monday, December 16, Dworkin said, a coalition rep dropped by the viaducts and saw that there were no Streets and Sanitation workers cleaning the underpasses. However, CDOT workers were telling the homeless people that they would have to leave the underpasses permanently because they were violating the law against blocking the public way.

Tom Gordon, the self-styled "mayor" of the camp contacted the Chicago Sun-Times about the issue, and after some news coverage and an email from the coalition to Mayor Lori Lightfoot's office, the following week the homeless weren't evicted. Streets and San simply cleaned the viaduct and picked up garbage.

Sill, Dworkin said, the practice of building sidewalk bike lanes in viaducts makes it more difficult to defend the rights of homeless people to camp there, since the tents are, in fact, blocking the public way. "We feel like there's just not that much we can do, except asking the city not to handle homelessness this way. It's clearly not a productive way to to handle it -- you're just chasing people off to the next spot."

Dworkin, who commutes by bike herself, said there were also homeless people sleeping in the Metra viaduct on Randolph Street between Canal and Clinton streets in the West Loop before CDOT installed a sidewalk bike lane there in 2016. "It's a terrible design," she said. At rush hour you've got to bike through crowds of people on Randolph crossing Canal."

On top of that, it would have been relatively easy to create protected bike lanes on the street, rather than the sidewalk, in all of these viaducts. Lawrence, Wilson, and Randolph all have multiple travel lanes, which likely provides more capacity than is needed for the amount of motor vehicle traffic they carry, which encourages speeding. So converting mixed-traffic lanes to bike lanes instead of placing the bikeways on the sidewalks would have made everyone safer, bicyclists, pedestrians, and drivers alike.