Update 12/24/19: Per a Chicago Department of Transportation spokesperson, the bridge has not actually opened yet, so please stay off it for now. "It is NOT open yet. There are still some final items that need to be finished before it opens. I don’t think it will be long, but I can’t give you a timeline right now."

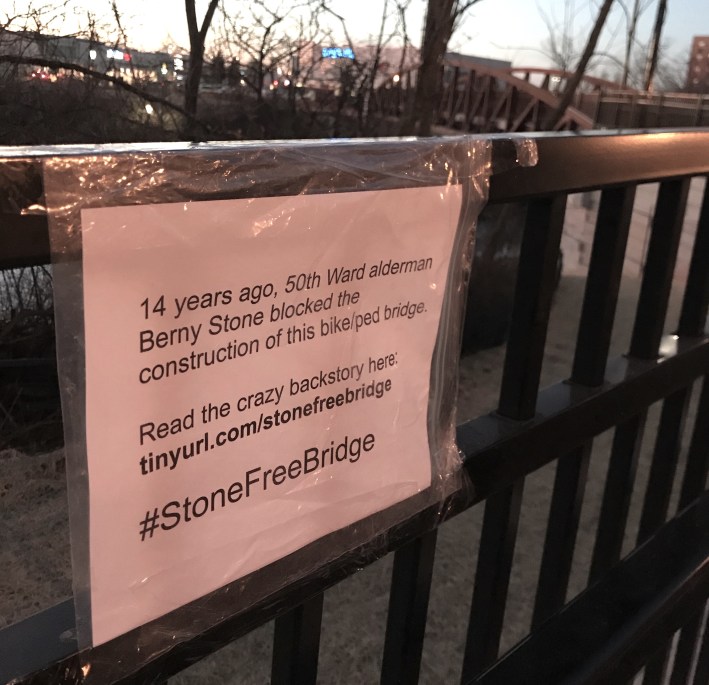

Fourteen years of frustration for cyclists finally ended this weekend as the the bike bridge that the late 50th Ward alderman Berny Stone blocked back in in 2005 quietly opened to bicycle and pedestrian traffic. I propose that we call it the Stone Free Bridge, after the eponymous Jimi Hendrix song, and in celebration of the fact that Chicago has largely moved past the anti-bike mindset that the cantankerous City Council member represented.

Officially called the Lincoln Village Pedestrian Bicycle Bridge, the $3.4 million, 16-foot-wide, 180-foot-long span provides the final missing link in the North Shore Channel Trail, which runs nearly seven miles from Albany Park to Evanston. Most of the path's Chicago portion hugs the east bank of the channel, but north of Lincoln Avenue the trail shifts to the west bank. The opening of the bridge means that people strolling, running, and biking are no longer forced to make the crossing via Lincoln or Devon, busy four-lane highways.

By 2005, the Chicago Department of Transportation had designed a bridge near this location and secured funding for it. Stone—who ruled the Far-North West Ridge neighborhood from 1973 until being beaten by current alderman Debra Silverstein in a runoff in 2011—originally endorsed the project. But he pulled his support after funding was secured, forcing the department to put the initiative on ice. (I was working as CDOT's bike parking program manager at the time but wasn't involved in bikeways planning.)

Stone gave various dubious explanations for his opposition to the bridge. On one occasion he said he was worried that cyclists coming off the bridge might be struck by drivers in the Lincoln Village Shopping Center's parking lot, even though the bike path was a significant distance from the lot.

He later claimed that he had vetoed the bridge because the eight-story Lincoln Village Senior Apartments building was being constructed just west of the trail near the proposed span site. "There's just no place to put a bridge," he said. However, the senior housing got built and the new bridge are currently coexisting nicely.

Yet another excuse he gave to CDOT for his opposition was that neighbors east of Kedzie, which parallels the east bank, were worried about people parking on their streets and using the bridge to access the Lincoln Village Shopping Center, west of the channel. But he provided no documentation to support this claim.

But former Active Transportation Alliance executive director Rob Sadowsky, told me that there was a racial element to Stone's bridge opposition. Sadowsky said that at a community meeting he attended in 2001, Stone referred to African-American and Latino youths as "little blacks and browns." The alderman implied, according to Sadowsky, that the ward should avoid measures that would bring more young people of color to the neighborhood. Stone's children have vehemently denied the claim that Stone was racist.

Stone passed away in 2014, so may never know the truth about his motivations. The important thing is that, while he's gone, the bridge is here, and it's a nice-looking facility that will make walking and biking safer and more pleasant in his former fiefdom.

Immediately after Mayor Lori Lightfoot's inauguration last May, she signed an executive order supposedly eliminating aldermanic prerogative, the de-facto practice of letting Council members have final veto power over projects in their wards. However, CDOT recently admitted that the aldermanic approval process for transportation projects haven't changed.

The Stone Free Bridge story is an example of just how long necessary infrastructure can be delayed if it's subject to the whims of local politicos. It's evidence of why we need to get rid of aldermanic prerogative for real.