Streetsblog reporter Lynda Lopez is a local leader when it comes to examining the intersections of transportation and social justice issues. So it wasn't surprising that she was invited to participate in the Chicago Center for Leadership and Transformation's symposium on gentrification, including discussion of displacement related to new transportation amenities, called "Who Is Chicago For?"

"Curious, confused or angry about what's happening in your neighborhood?" said the event invite. "Folks moving in, people being pushed out... Join us for our first learning circle featuring a conversation about displacement and gentrification in Black and Brown communities." In addition to Lynda, the panel of speakers, moderated by CCLT's Charlene Carruthers, also included WBEZ's Natalie Moore and Tony Woods from the Inner-City Muslim Action Network.

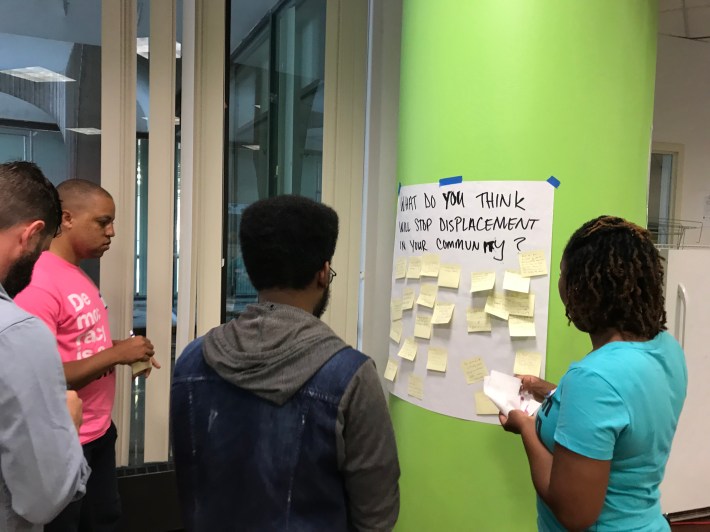

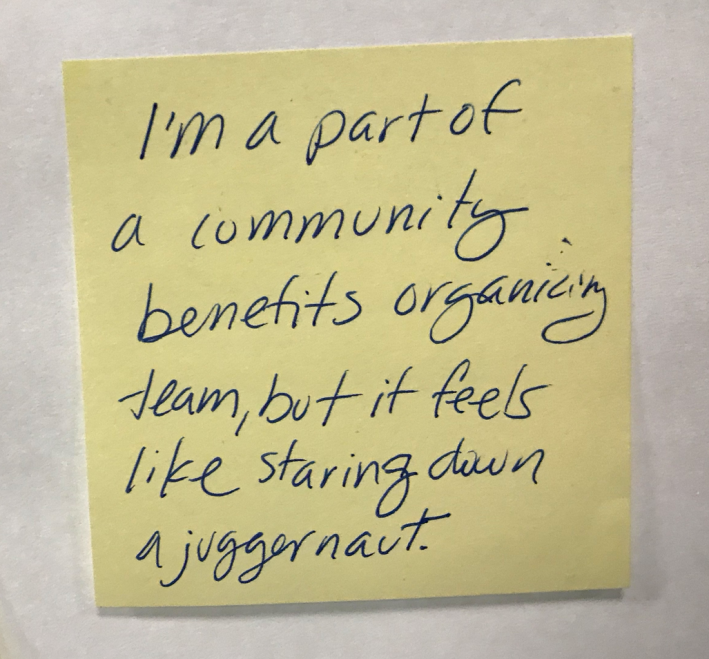

Carruthers kicked off the event by defining housing displacement as the forced removal of longtime residents who are priced out of their community by rising housing costs, and characterizing gentrification as "modern-day colonization." She invited attendees to answer three questions with Post-It notes on display boards: "How is displacement impacting your community?" "What is being done about displacement in your community?" and "What do you think will stop displacement in your community?"

"Forced assimilation and cultural erasure," wrote one attendee in response to the first question.

"Rogers Park and Uptown are the last affordable and integrated neighborhoods on the North Side, so white middle- and upper-class folks from the surrounding areas are slowly moving in," said another.

"Black and Brown people must be able to accumulate wealth by owning their own homes," wrote another participant, suggesting a solution to prevent displacement.

"Rent control, mixed-income affordable housing; strong community public schools," recommended another attendee."

One participant called for negotiating a community benefits agreement of the Obama Presidential Center in Woodlawn, and cited the Elevated Chicago initiative to promote affordable transit-oriented development.

During the panel discussion Carruthers asked the panelists to address the three questions. Moore argued that gentrification is class-, not race-based, "but class and race are first cousins." She noted that Black people can be gentrifiers, but added that studies show that displacement of lower-income residents tends to happen more slowly when the more affluent folks moving into an African-American neighborhood are also Black.

"Data shows that the Black middle class is disappearing in Chicago," Moore said, noting that African-American neighborhoods still have't recovered from the 2008 economic crash. She argued that the growing wealth gap in Chicago is reflected in the fact that the ALDI discount food store chain is currently the leading grocery store in Chicago, but we're also seeing a boom in the relatively upscale Mariano's supermarkets.

In response to the question, "What is preventing Chicago from being for everyone?" Moore cited race-neutral policies as being a problem. For example, she acknowledged that the city's transit-oriented development ordinance, which allows developers to build more housing density and fewer car parking spots on land near transit, is beneficial in that it decreases driving. However, she noted that most TODs have been built in affluent and gentrifying neighborhoods, so the policy hasn't been as helpful in Black and Brown communities on the South and West sides, where retail and other destinations tend to be fewer and farther apart, which makes it harder to get things done without driving.

When it was her turn to answer the question "Who is Chicago for?" Lynda noted that the "Building a New Chicago" signs that were posted by infrastructure projects under the Rahm Emanuel administration seemed to raise that question -- who were the projects intended for, current or future residents?

She noted that when she was growing up in Humboldt Park, her school and library were near her home, and her mother was able to walk to work. "There were all these messages that this neighborhood was for me," she said.

However, while attending the University of Chicago, she became aware of the history of the school's influence on local housing and retail, such as the demolition of low-cost housing and independent businesses during the Urban Renewal period. She also brought up the concerns about rising housing costs associated with the Obama Presidential Center.

After college Lynda moved back in with her family, now living in the Hermosa community, and got involved with affordable housing issues through groups like the Logan Square Neighborhood Association, addressing concerns like rising rents and home prices along the Bloomingdale Trail corridor. "Some people say that the neighborhood is in a pre-gentrification period," she said. "Logan Square gentrification is really in your face, but some of the same things are happening in Hermosa.

She noted that her family still lives in Hermosa and hopes to buy a home there after renting for years, but home prices have risen significantly in recent years. "I hope my family can remain there."

Lynda added that she dislikes assertions that "Logan Square is gone" or "Pilsen is gone" in terms of being completely gentrified, calling them erasure of the fact that many longtime residents of color are still living in these communities, she said. "People like LSNA are still on the ground and fighting."

Tony Woods discussed IMAN's "Light in the Night" initiative, which includes hosting three events a week to provide a safe space for residents, with free food, information about community resources, and family-friendly activities. He noted that while young men, the demographic that is most likely to get caught up in crime and violence, often stand on the periphery of these types of events, IMAN makes a point of reaching to them and establishing relationships, in hopes of eventually connecting them with job training opportunities and other resources.

"Who is Chicago for?" Woods said. "I don't think it's for us at this point, but it should be for everyone." He noted that recent studies have found a 30-year gap in the average life expectancy between Streeterville and Englewood residents, and a $100,000 income gap. "The disparities are crazy. We're living in a city divided."