This article also ran in the Chicago Reader.

The future of venture-capital funded dockless bike-share in the U.S. isn’t looking so bright right now. Also nicknamed “DoBi,” the technology lets customers use a smartphone app to locate and check out bikes scattered around the service area. Most companies use cycles that are only secured with a built-in wheel lock, which makes them easy to steal or vandalize. Last month a Washington, D.C. city official reported that some companies in the District have lost about half of their fleets.

Another sign that the American dockless bike-share bubble may be bursting is the retreat of the Beijing-based company from most of its U.S. markets. Chicago launched a DoBi test on the Far South Side in early May but Ofo left the pilot in a huff on July 9.

At the time, staffers claimed the company was fed up with our city’s rule allowing firms with “lock-to” cycles (with built-in U-locks or cables for securing them to racks or poles) over ones like Ofo with “wheel-lock-only” models. The former may release up to 350 bikes, while the latter can only put out 50. But a few days later that claim proved to be sour grapes when Ofo announced that it was abandoning almost all of its other American cities.

These troubling developments don't necessarily mean that Chicago’s dockless program is doomed, however. We still have three other companies in the pilot, which includes almost all of the city south of 79th. LimeBike has 50 bright-green, wheel-lock-only bikes here with electric motors that make pedaling easier. Pace has released roughly 350 blue-and-white, lock-to, non-electric vehicles. And Jump Mobility, which joined the pilot on July 2, is deploying a similar number of red lock-to cycles that feature an electrical assist.

Representatives for LimeBike and Pace painted a relatively rosy picture. (Jump didn’t respond to questions.) “Despite the limited number of bikes we are allowed to operate in the pilot, we passed more than 3,000 rides at the end of July, which demonstrates the demand for DoBi exists,” said Chicago manager Jessie Lucci.

Likewise, Pace expansion manager Dave Reed said his company has been “very pleased” with its Chicago ridership growth. “Recently, we have been focused on driving repeat ridership, and have seen those efforts start to pay off as our number of trips per rider has increased 66 percent.”

The vendors are required to provide the city with monthly trip data, plus reports on maintenance and customer service. I obtained these records for May and June through a Freedom of Information Act request. It turns out that LimeBike saw many more rides during those months than its competitors, with 1,170 trips taken in May and 1,137 in June, compared to Pace’s 343 rides in May and 962 in June, and Ofo’s 416 trips in May. (There was no June report for Ofo, presumably because after the company quit the pilot in July it didn’t bother to turn one in.)

LimeBike’s stronger ridership numbers are despite the fact that it only had a fraction of the cycles on the street as Pace. LimeBike is also more expensive at $1 to unlock plus 15 cents a minute to ride, versus $1 per half hour for Pace and Ofo. Jump trips cost $2 for the first half hour, plus seven cents for each additional minute. LimeBike may have had an edge before Jump joined the pilot because they were the only company with electric bikes, which are handy for covering longer distances.

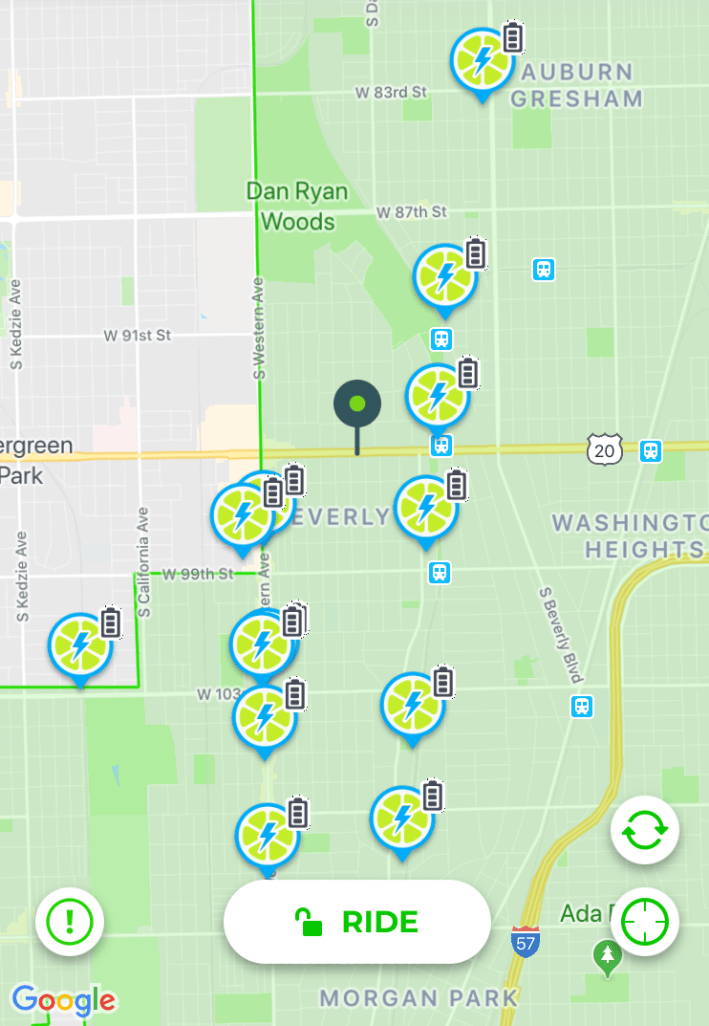

To promote geographic equity, the pilot rules require the vendors to keep at least 15 percent of their fleets in each of the four service area quadrants. When I checked out the apps last week, the Pace and Jump bikes were spread fairly evenly across the pilot zone, but almost all of the LimeBikes cycles were clustered within or near Beverly. This majority-white neighborhood is the most affluent community in the pilot zone, as well as the most bike-friendly – it hosts an annual bike race as part of the Intelligentsia Cup series.

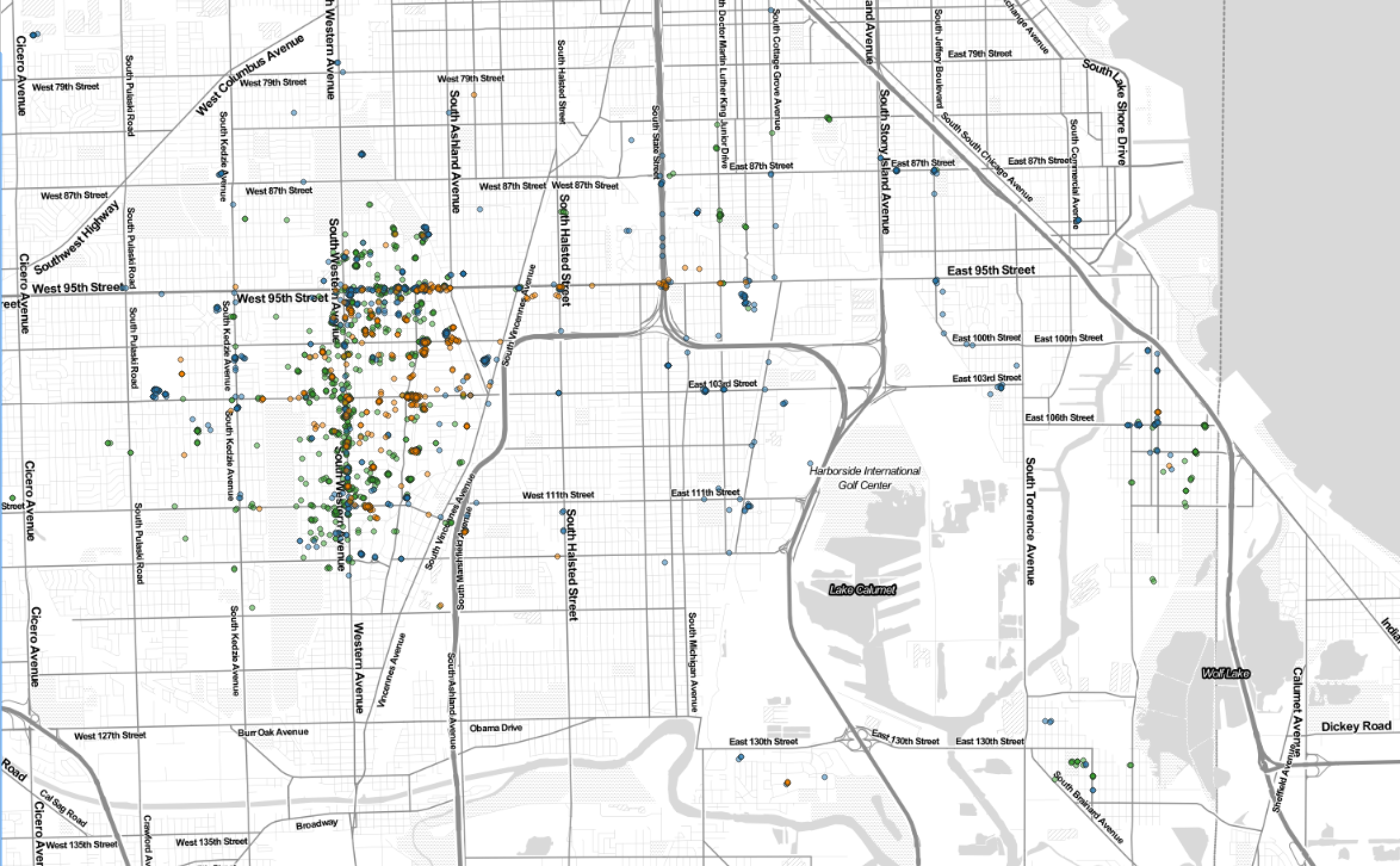

As such, Beverly is low-hanging fruit for bike-share, whose users tend to skew white and wealthier. When my writing partner Steven Vance plotted the May and June trip data on a map, he also found that the vast majority of all the DoBi trips started in or near Beverly.

The maintenance reports suggest that vandalism has been relatively rare, possibly thanks to the fact that most bikes are lock-to. That jibes with what Beverly-based bike advocate Anne Alt told me. “I’ve seen only a few damaged bikes,” she said, adding that it’s unusual to see poorly parked bikes blocking sidewalks, which has been an issue in other cities where wheel-lock-only cycles are common.

Last week after work I took a spin around much of the service area, including sections of the popular Burnham Greenway and Major Taylor Trail bike paths. While dockless bikes were a common sight, I didn’t actually see anyone using them. In fairness, I didn’t make it to Beverly, where bike-to-train commuting is common, until well after rush hour.

One downside of lock-to technology was apparent in business districts with bike racks, where just about every rack had at least one Pace or Jump cycle on it, reducing parking for private bikes. To address this, the city is installing 100 more racks in the pilot zone, bankrolled with vendor permit fees. Pace also plans to install 25 of their own multi-bike racks on private property, plus 25 more in public parks.

Another takeaway was that many residents are unfamiliar with how the dockless systems work. LimeBike and Pace say they’ve worked with local job-training programs to find employees, and they’ve also been hosting group rides with community organizations like My Block, My Hood, My City, and the far-south bike group We Keep You Rollin’ to introduce residents to the technology.

Still, a young father watchinging his kids play in Golden Gate Park, the starting point for We Keep You Rollin’ rides, said he had no idea how to use the public bikes. Four Jump cycles were locked nearby. “They just put them out and don’t inform us about how they work,” he said.

In Hegewisch, the Baltimore Avenue business strip was lined with DoBis. Longtime resident Linda Aloia was relaxing with family members on her front steps. “Once in a blue moon you’ll see people riding them,” she reported. “I think a lot of people want to, but they’re not sure how you check them out.”

Northwest of there in Trumbull Park, several Pace bikes were locked to racks next to CTA Jeffery Jump express bus stops. Nathaniel Terrell, who was waiting for a ride, was skeptical, and didn’t seem to view the bikes as a handy commuting tool. “I don’t really see the usefulness unless you want to go out for a ride with your girl or whatever.”

But over on the Burnham Greenway in the East Side neighborhood, retired glass worker Alfonso Gomez said he thinks the bike-sharing program is a good idea. He was cycling with his sandy-colored dog Güera (“Blondie”) in a crate on the back. “Lots of people in this neighborhood ride bikes.” However, he admitted he had no idea how to rent a DoBi

So while the numbers and anecdotal evidence suggest that Chicago’s dockless pilot is going reasonably well, if we want to expand its appeal beyond the early adopters in Beverly, it sounds like more DoBi-vangelism is needed.